|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Talking to Lynn Stegner

|

| Lynn Stegner |

Lynn Stegner was born in Seattle, Washington. For the most part she grew up in northern California where she attended the Convent of the

Sacred Heart in Menlo Park, and subsequently the University of California, Santa Cruz from which she graduated with highest

honors in the field of Literature with an emphasis in Creative Writing. In 1986 she married the novelist, historian, and essayist,

Page Stegner, and two years later gave birth to their only daughter, Allison (now a junior at Stanford University). With publication

of her first novel in 1991, she sold her share of the wine company in order to cut down to two fulltime jobs: mother and writer.

Lynn

has been the recipient of, among other honors, a National Endowment for the Arts, a Fulbright Scholarship to Ireland, and

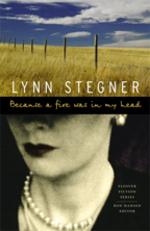

a Western States Arts Council Fellowship. She is the author of four novels: Undertow and Fata Morgana, both of which were nominated for the National Book Award, Pipers at the Gates of Dawn, a novella triptych, (one of the three novellas was awarded the Faulkner Society’s Gold Medal for Best Novella of 1997);

and Because a Fire was in My Head, which won the William Faulkner-William Wisdom Award for Best Novel of 2005 and which became a Literary Ventures Selection

in 2007. She has also written a critical introduction to her father-in-law’s short fiction, the Collected Stories of Wallace Stegner, as well as editing and writing the foreword to a Penguin edition entitled Wallace Stegner: On Teaching and Writing Fiction. Lynn herself has taught writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz, the University of Vermont, the National University

of Ireland, Galway, the College of Santa Fe, and for a number of years she directed the Santa Fe Writers’ Workshop.

She is currently at work on a volume of short stories, THE ANARCHIC HAND, and will be teaching at Stanford this coming fall.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A brilliant marine biologist’s

last and best chance for happiness in a relationship is threatened by feelings about an abusive father. The relationship she

shatters with a senseless infidelity resumes on solid ground when, while doing research on killer whales, she faces her own

needs and begins to stand up for them.

Kate Riley is an unusual

heroine, a beautiful, ambitious woman who rejects the conventional roles of women in her 1950s rural community. The premature

death of her beloved father, coupled with a corrosive relationship with her mother, prompts Kate to flee her hometown in desperate

search of happiness and approval. Set against the backdrop of the sweeping social and economic changes that followed World

War II, the story takes us from the plains of rural Saskatchewan to the bustling cities of Vancouver, Seattle, and San Francisco—through

a succession of lovers, and of children born and abandoned, as Kate makes one bad choice after another.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

RUSSELL ROWLAND, TSP co-editor: How was your journey to publication? Were you working on Undertow

when you were in school, or did that come later?

LYNN STEGNER: I didn’t begin composing the

novel, Undertow, until eight or nine years after I earned a degree in Literature/Creative

Writing, and that was for the oldest reason in the world: I had to make living. I chose a profession that would eventually

allow me time to write, I thought, but that plan didn’t bear fruit as quickly or as abundantly as I had fantasized.

What did I know? I was 22 and on my own. I had an old Volvo that wouldn’t start in the rain and a $200 a month apartment.

After working for a wine company in San Francisco where it was discovered I possessed a freakishly good palate, (they even

sent me to France for additional training) I decided that I’d have even more time to write if I owned my own company.

Another of the Great Fallacies. So a friend and I started our own wine company, and of course I worked twice as many hours

and made half as much for about six years more, until finally I was making enough to cut back to half-time and commence work

on Undertow. I had been writing throughout those years, mostly stories, journal entries, wine articles, some of which ended

up published. Writing a novel – for me, at least – requires a ritual of time and stability, boring stability and

routine friends might readily describe as a rut. I wrote from 3:00 am to 7:00 am, at which point it was time to get ready

for work. One story got me a fellowship to the Squaw Valley Writers’ conference, which was the only way I could have

gone in those days. And so it went. All along I was researching and making notes for the book. I had a wonderful agent, one

of the best – Don Congdon – and he was a great supporter of that first novel, loved all the marine biology and

in fact, it was Don who advised me to add the last two chapters. Then he started shopping it around; there was interest, and

praise for the prose, but no buyers. I began to worry that my last name might be subliminally encouraging higher standards

than a first novel usually attains. And so as an experiment, and without implicating Don, I sent a copy of the ms minus the

Stegner, just Lynn Marie, to a relatively newish house based in Dallas and Dublin – Baskerville. They wrote back within

two weeks, asking about some missing pages, forty in total, and saying that they were very interested, and also asking whether

or not I’d be willing to use a pen name, as “Lynn Marie” wasn’t really working for them. Sounded like

someone who wrote Romance novels, they said. I then confessed my full name, and they were quite satisfied. I remember going

over the last 100 pages of the galleys with my editor from a pay phone at Phantom Ranch in the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

I’d waited eight years to get a private permit to run the Colorado, an eighteen day trip, and the galleys deadline coincided

with day-five.

RR: Undertow received excellent reviews, and was nominated for the National Book award,

and all four of your novels have been critically acclaimed. How satisfying is it to you that you’ve been able to carve

out such respect among the literary community?

LYNN STEGNER: Well, it’s deeply satisfying, it’s

practically everything – everything that doesn’t have to do with the writing itself, which is its own private

and ongoing reward.

RR: On the other side of that, does it bother you at all that you haven’t

gained more recognition among the commercial crowd, or has that ever been a consideration?

LYNN STEGNER:

I think every serious writer dreams of being a commercial success so long as it doesn’t countermand aesthetic imperatives.

But that’s a pretty big caveat. The bubble burst for me after the second novel. By the time the third book came along,

a novella triptych, not exactly a highly recognizable form and so not a highly marketable book, I understood that I probably

wasn’t ever going to make any “real” money with my work. I was lucky enough that the gods were letting me

write what I wanted to write -- character-driven narratives that are a form of dramatized belief, to borrow a phrase from

my father-in-law, stories that ask something of readers, imaginative engagement, etc. And I have been additionally lucky in

that I could scrape together part of a living teaching and editing and winning awards or fellowships, and all along a solid

critical history was building up under these clay feet. With each publication I felt I was being handed a ticket to ride,

the moral authority to keep writing. I have a friend, a retired investment banker, who asks me now and then why I don’t

write just one big pot-boiler, something that’ll make me some heavy coin, and then return to what I want to write. My

answer each time: I would if I knew how. But really, would I? The trouble is, a writer only has so much of that special brand

of energy that can arrange words on a page in ways that are meaningful and beautiful, and even when one is composing something

that is perhaps less meaningful, even shallow and easy – easy to write and read – it still draws from that same

reservoir of creativity. At the end of the day you don’t have anything left for the stuff you care about.

RR:

Wallace Stegner is one of the most highly respected writers of this century, especially among writers in the West. How much

of an influence was your father-in-law on your writing? And what were the most important lessons you learned from him, both

as a writer and as a person?

LYNN STEGNER: He was an important influence, which may sound mild but

is not, in fact. What I mean to say is that of course he was terrifically influential but I was terrifically prepared to be

influenced by such a man and such a writer as he. When I met him I was already hardworking, disciplined, driven to write,

(and I mean daily and at ungodly hours); I had a certain knack with the language; my history had been difficult and therefore

humanizing enough to bestow a generalized compassion and, I like to think, a deeper understanding of humanity. I admired his

work, and so was disposed to learn from it. As a person he taught me a hundred different things from the serious to the humorously

serious. I’m thinking of one in particular – never accidentally insult. Similarly, as a writer, there was so much

about my nascent work that was already leaning toward like impulses and imperatives that the lessons came thick and fast and

. . . the word naturally comes to mind. The most important thing I learned from him about narrative? Point of view. Finding

the right one for the story or novel, the one that will properly control thematic revelation and at the same time maximize

the drama. One thing I did not learn from Wally is humility, which is not to say that he was or wasn’t a humble man,

only that he did not make public that aspect of his relationship to his work. I have always felt immensely humbled not only

by the opportunity that writing fiction presents, but also by the art form itself, which offers up so much artistic and spiritual

potential while at the same time demanding more than seems possible from the heart and mind in sometimes uncertain unison.

RR:

How do you see Wallace’s legacy in American literature, and how would you say that legacy has affected your approach

toward what you want to accomplish with your writing?

LYNN STEGNER: His legacy: what a broad canvas

that is. Grand too, about as grand as the land he loved. I’m not sure I’m qualified to answer that question, certainly

not all of it because I’m not a historian, which is one of the things he was. Or a biographer. I guess one thing I’d

say is that he gave the American West a voice that could be heard and appreciated in the rest of the world, even in New York

City. And it was a deeply credible, eloquent voice that, along with a handful of others of his contemporaries, has so far

defined 20th century America in imaginative terms. Through his books, especially his stories and novels, readers can experience

not only a life that was, but a country that was still becoming and a national character that is yet evolving. I might also

say that he enriched American culture to the extent that he actually changed it by reaching higher and further and in that

way telling us that more is, and will always be, possible. He wanted for himself, for his students, for his literary colleagues

that we all write better books by first being better people. Back to dramatized belief, and a civilization to match scenery.

It was all of a piece for Wally. You could not write serious literature if you were a frivolous person – another of

his precepts. How has that affected my approach to my own work? I suppose it confirms what I have believed all along, though

could not have clearly articulated, especially in the early years. I was what used to be known as “a serious girl”

and probably could have done with the occasional dose of frivolity. That answers the question relative to Lynn the person.

As far as the work goes, Cyril Connolly said it best for me: “The true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece

and … no other task is of any consequence.”

RR: Both Undertow

and Because a Fire Was in My Head feature protagonists who have struggled to overcome

very difficult childhoods, characterized by self-absorbed mothers. How much of that dynamic is formed by your own experience,

and how has writing about that affected your attitude toward your own history?

LYNN STEGNER: First

novels, and Undertow is no exception, tend to incorporate more autobiographical

material than later works. By the time a young writer is ready to compose a first full-length narrative he or she has accrued

at least a couple of decades of experiential debris. It’s in the road and it needs to be written out of the way. So

quite often that first novel does a lot of the heavy lifting. That being said, no one’s life facts and factoids are

all that interesting until they’ve been liberally subtracted from, then sifted and shaped and arranged, and until the

whole thing has been melded with imagination, and run through the mill of artistic sense and sensibility. At the end it’s

someone else’s story and someone else’s mother. And it’s that, that distance, that thoughtful, imaginative,

creative recasting of people and events that heals whatever healing may be called for. As for my own past and whatever I did

to it and with it in various books, it seems to have become just that: past, and satisfyingly so. There may be some residual

reflexes and allergies—there always are—but nothing a good story can’t alleviate.

RR:

Anne McBain, Undertow’s protagonist, is a marine biologist, as is Elliot,

her married lover, and I found the details you included about their work to be fascinating as well as very accessible. How

much of this knowledge was based on research, and how much comes from personal experience?

I also loved how much of

their work proved to have such a direct influence on their relationship. For instance, when Anne and Elliot are tending to

an injured seal, and Anne subconsciously flirts with another biologist who is trying to help, she is suddenly jolted out of

what she’s doing when the seal dies. Did you find that these parallels emerged naturally as the story unfolded, or was

some of that intentional?

LYNN STEGNER: Unlike Henry James, whose characters never seem to have jobs

or occupations, I want my characters to have something they must do each day, something they care about and that tells a reader

who they are in part. From those callings or careers a great wealth of metaphor, of emotional understandings, of connection-making—and

losing—can arise. I’m not a marine biologist, but I did my homework. I made numerous trips out to Ano Nuevo Island

along the coast of California where the Northern Elephant Seal population breeds and molts; I spent two weeks up in Johnstone

Strait, British Columbia, a place where it can rain 24 inches in 24 hours, with a cetacean expert, studying Orcas. I read

dozens of books and articles. And I’ve passed many of my own childhood days on boats in the San Juan Islands and Puget

Sound, as well as living over half my life on the West Coast. After a while the sea and what happens at its edge becomes one

plank of your personality, your identity. That research was easy because salt water was already in my veins. But when I was

preparing to write Hired Man, the first novella in the triptych, Pipers at the Gates of Dawn, about an eighteen-year-old dairy farmer in Vermont, I did another sort of homework.

Knowing nothing experiential or even vicarious about the life of a dairy farmer, I thought it prudent to spend some time milking

cows, which one summer I did, and many mornings too at 4:00 a.m. I talked to the local farmers, interviewed the local vet,

I read old dairy reports and dug through the back bins of the village historical society, since dairy farming has changed

surprisingly little in 200 years. This is all part of the respectful preparedness essential to the kind of fiction that a

reader can believe in his gut. If the characters are living out their fictional lives on the page in a realistic and accurate

way, then naturally the things that trigger an emotion or a memory or the often-necessary narrative exposition will be things

that are integrally a part of those lives.

RR: Anne’s incestuous relationship with her father

is as heartbreaking as any I’ve ever read, especially in the scene where she tries to tell him she’s not going

to continue. This becomes especially relevant to the story when she becomes involved with Vinny, who admired her father so

much. How much of Anne’s character is formed by this relationship with her father, and how does her view

of it change

after he’s gone?

LYNN STEGNER: More of Anne’s character is formed and informed by her

relationship with her father than she’s able to admit, but she’s young enough to believe that with hope and intent

and a lot of industry, she can leave it behind. His physical death is of course a kind of red herring exposed by her misadventure

with Vinny. She can never fully escape her father and the past, but she finds ways to manage the legacy. Nabokov says in Lolita,

or he has Humbert Humbert mentally observe, that he broke her life, not her heart. Life, in this case, seems a kind of shorthand

for soul. Hearts can heal over, fall in love again, even forget. But the soul is the tabla rasa, and once it’s writ

upon, the words and wounds cannot be erased. At the end Anne tries to view her father and what happened as dark gifts that

shape outward from within. Her dream is simply to have a normal life, to not let what happened ruin her—a reasonable

and quiet sort of triumph. When the novel concludes she seems to have a fairly decent shot at just that.

RR:

I know that Because a Fire Was in My Head germinated for about twenty years before

you were able to write it. What was it that you learned during that time that enabled you to feel ready to write this story?

LYNN

STEGNER: The first word that comes to mind is compassion, but that’s not quite right. Twenty years ago I don’t

think what I lacked was compassion. Neither is compassionate understanding, which, after all, with the right set of data,

is not that difficult to find even for the least of us. As Jean Renoir once remarked, “You see, in this world, there

is one awful thing, and that is that everyone has his reasons.” Kate Riley has her reasons, some of them very good.

No, I think what I learned was that some people really do fail, some people really can live and die without redemption, without

even wanting it, and in Kate Riley’s case, finally rejecting it. Of course I’m not talking about any sort of dogmatic

or religious redemption. For someone like me, who believes in Belief, in the human capacity for positive change; for someone

like me who believes in simple kindness, which may be a miracle as Mary Oliver suggests, it was a long time before I learned

to give up on people. Not many, but a few. I guess that’s what I learned. How to give up. In a way, it is the common

form of forgiveness.

From a technical perspective, and after writing three novels, I learned how to manage narratively

an enormous time span and five major settings within a limited page frame, as well as how to break some of the rules, like

the almost-always-fatal late arrival of major characters.

RR: Kate Riley has to be among the most

self-absorbed characters in the history of literature, and yet you bring such a sense of understanding to her actions that

it’s hard to actually hate her. How did you approach this character to avoid making Kate so unlikeable that your readers

would throw the book against a wall?

LYNN STEGNER: Well, as I mentioned in the last answer, I gave

her reasons for her subsequent conduct. They are not by any means justifications, but they do help the reader understand why

she does what she does, why she chooses one course over another, more worthy course. Those first sixty pages that evoke and

to a limited fictional extent, document her childhood are there to help explain her later life, and to load the spring, as

it were. By the time she leaves Saskatchewan she is fully coiled, she is taut with resentments, with wrongs that can never

be righted, yearnings that have no hope of requital.

RR: Kate actually ends up learning very little

about herself during the course of this novel, which goes against the conventional approach for most novels. How did you see

the message you wanted to convey coming out in this book if not through the protagonist?

LYNN STEGNER:

Rather than the main character singing the song of her life, which is entirely possible and probable with fairly reliable

narrators, this novel invites more from the reader. Because Kate is hardly a reliable witness to her own life. So the thematic

conduit takes the form of a call-and-response. I suppose I expected the collective reader to volunteer where Kate so obviously

failed, to see the strong course when she chose the weaker one, to feel compassion when she plunged into narcissism. And mostly,

to understand how this sort of story can happen, how something can break too early, too traumatically, and how people, for

a combination of circumstances and reasons, may never recover, never see out. Maybe we learn something about ourselves through

Kate’s not learning anything, or learning too little too late. A communal exercise in negative capability.

RR:

After sticking fairly close to Kate’s point of view throughout this novel, you add a few chapters at the end from the

point of view of her children. What was the intent there? Do you think Kate is redeemed at all by the realization that her

condition is ‘not compatible with life’?

LYNN STEGNER: I decided to have her three surviving

children speak briefly at the end for several reasons. First, they are her immediate victims, and I felt they should have

their say. Secondly, they represent the future, a future away from Kate Riley and the life she led, the wake of destruction

she left behind. And thirdly, in terms of narrative structure, they act as a kind of Greek chorus, both explaining and offering

commentary on the life of their mother. It seemed only fair, to give them the last word.

RR: What

is your writing routine? Do you do a lot of rewriting as you go, or are you more inclined to write several drafts? What would

be the ideal situation for you as a writer? Do you learn from teaching, or are you more inclined to prefer writing full-time?

LYNN

STEGNER: I plan to write every day, which usually means that only one or two days a week are lost to life’s

interruptions. My study is a separate structure from the house and even that brief exposure to the outside, whether to snow

falling or lupine blooming along the path or to sage drying after rain, serves to properly and effectively delineate my lived

life from my imaginative and thinking life. I work usually from 8:30 until lunchtime, and after that break, I return for an

hour or so to see what I’ve done and maybe clean it up some. I rewrite as I go along, sometimes more than I should.

There have been occasions on which the first thrust into the material was the cleanest and brightest, and reworking it has

only muddled it and robbed it of vitality. But usually by the time I actually reach the end of a chapter or a book, it is

pretty much done. I have always had to go back and tinker with the opening chapter, to settle stray plot elements or tweak

the tone to harmonize with the late chapters. Once I had to change the name of a character after I had lived with it for over

three years, because my agent observed that it was the name of a well-known mystery writer. In terms of writing, my “ideal

situation” is the one I have, the one I planned for back when I was in the wine business. Every now and then I end up

with too many editing projects, or a class that is gobbling up writing time, but I’ve learned how to say no, too. I

love to teach, not too much. I still need income, after all. And it’s important to stay in the conversation with younger

writers and with colleagues. There’s a danger, I think, in drifting so far out of the current that you risk becoming

eccentric in subject and style and talking only to yourself. Art, and especially literature, is first a form of communication.

|