|

|

|

|

|

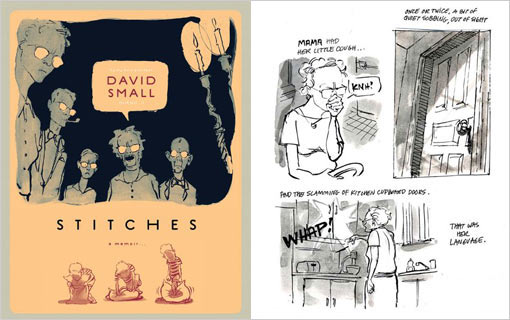

| David Small |

Talking to David Small

Zinta

Aistars

We stand in the drizzling

rain in the car pool lot next to Interstate 131, waiting for all Book Mavens to gather. Once a month we meet to talk about

good and great books. Often we meet at one of our homes, sometimes we meet at the organic restaurant in downtown Kalamazoo—Food

Dance Café—for breakfast and books. Today we are on a field trip.

Regular readers of

The Smoking Poet no doubt enjoyed the Book Mavens interview with author Marge Piercy in our Spring 2010 issue. As

spring heats up toward summer, this literary group of women has decided to meet another author with Michigan roots—David Small. Indeed, on this drizzly day, we are getting two authors for the price of one. Sarah Stewart, David’s wife, will be alongside him as we all meet for a book club lunch at The Public House in tiny town Mendon, tucked away in the green and lush countryside of southwest Michigan, on the edge of St. Joseph River.

David Small and Sarah Stewart

live in an 1833 farmhouse on the edge of Mendon. They are a wonderfully collaborative team of author and illustrator, author

and author, and together have filled bookshelves with award-winning children’s books. Often, Sarah is the writer, David

the illustrator. Their book, The Gardener, won the 1997 Caldecott Honor and The Christopher Medal. And there are many more such books, many more such accolades.

Today, however, the Book

Mavens are piling into our cars and heading south from Kalamazoo and into the country to talk to David about Stitches.

We chatter as we drive.

“Amazing, isn’t

it? I never read graphic novels. Well, graphic memoirs … never! But this. This!”

“A few words, images

in gray and black and white, and yet I was so moved … “

“To tears.”

“I was up all night

when I got the book. And then I thought about it all the next day.”

And so we chatter, remarking

on the wonder of this book, Stitches. None of us have ever seen a memoir done in this way—329 pages of graphic

images, comic-book style, except that instead of caped super heroes rescuing damsels in distress we read about little boy

David, growing up in Detroit, Michigan, in what can only be called an abusive household, in the midst of a dysfunctional family,

trying desperately to rescue himself.

Mind you, this isn’t

a story about a screaming household, a wife-beating drunkard of a husband, or criminal activities. This is more of, well, the

dysfunctional sort of abuse that happens in a subtle and silent manner, keeping an orderly public face to the curbside,

rustling with silent suffering and anxiety on the inside. After all, David’s father, Edward Small, was a Detroit physician,

and his mother, Elizabeth, ran a tight and neat ship of a household. Wasn’t this every other nice family?

It was not. In Stitches, a

quiet rage seethes, frustrations bristle, parenting mistakes are made with traumatic result. David’s mother has herself

been victimized as a child by a mother of questionable sanity, and as the pattern often goes, she brings that same manner

of abusiveness to her own family. She is, we eventually learn, a closeted homosexual, and her marriage is built on false pretense.

Her buried needs and feelings express themselves in stinginess and scolding. She slams kitchen cupboards a lot. David’s

father, meanwhile, throws himself into his work with wild abandon, seemingly wishing to cure all ills by radiation, subjecting

his young son to heavy doses almost as if a form of recreation. His father withdraws into the basement a lot,

beating up the punching bag there while the cupboards slam upstairs.

|

| The Public House Restaurant and Tap, Mendon, Michigan |

It’s a child's nightmare,

and David Small’s images use few words and spare, swift lines, yet convey his nightmarish childhood with

precise emotional impact and power. We feel his horror as he wakes up in a hospital room, his throat stitched where a cancerous

vocal cord has been removed, a result of too much radiation at his father’s hands. No one tells him what is happening.

No one talks to him. No one hears him. He grows ever more silent, his own voice coming through instead in his art.

We want to hear him speak

now. If no word seemed missing in Stitches, still, we want to hear David Small tell us more about what happened between

the lines, after the lines were done.

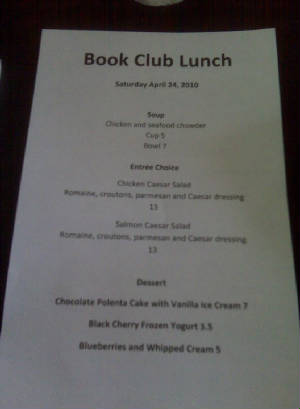

In Mendon, when we arrive

and pile out of our cars, we find The Public House closed to the public, but open just for us. A waiter graciously seats us

at a long, neatly set table, serves us tea and wine, hands out menus prepared for our meeting with David and Sarah.

They arrive, and it is Sarah

who speaks first, shining with pleasure at the attention given her husband. “He is a creative genius!” she says,

and adds, “I would stand in front of a bullet for him … “

|

| David has the Book Mavens in "stitches." Sarah Stewart in black cap. |

So it is established—ending

of this story before we even begin: David’s traumatic childhood has finally brought him to a marriage that is a true

partnership, built of shared interests and passions, a mutual admiration society of two. David smiles, a little shyly, as

Sarah speaks so highly of him.

But then we all want to

hear the story behind the story. How did Stitches begin, where was its seed and what its first signs of growth?

“The body never lies,”

he says. As our lunches arrive, he tells us about the accumulation of unexpressed stress in his body, inexplicable swellings

on his neck, as if words were stuck there and pressing to get out, to get out, out …

“I knew it would never

be a novel,” he says. “I’m not a writer. I don’t move among words and grammar with grace. But I thought

about a memoir, continued to think about it, dream about it. My dreams continually reminded me of the past. I saw a friend’s

graphic novel and was intrigued. I realized I could tell a story in a very visual way … I

still thought I had no real story to tell, but I just started to draw … “

And he kept drawing. And

kept drawing. Feverishly. Night after night, then weeks, then months, through passing seasons, images pouring out of him.”

“Purging,” David

says the word thoughtfully. “That would be the word for it.”

He found that he could bring

his mother alive on the page, so much so, he says, that it was almost … disturbing. All over again. There she was, a

malevolent presence. “In a very real way, she was back with me.” David felt his own rising rage as he drew the

endless strings of images. He felt the swelling in his neck where a scar attested to past surgery, his body expressing what

his mind yet couldn’t. He kept drawing.

“I had to express

this or it would kill me.”

An agent glimpsed some of

his drawings and encouraged him to keep going. So David worked, completing other picture books on the side, but ever returning

to his graphic memoir, until three years later, it was complete.

When Stitches was

published, acclaim poured over the artist, as well as vindication. He received e-mails and heard stories from others in their

own processes of purging. Relatives and old neighbors surfaced to offer memories of David’s childhood that were echoes

of his own. He found out about the death of his grandmother, one of the most coldly abusive characters in Stitches,

who had passed away in a mental hospital. He spoke again to his brother, with whom he had lost contact over the years.

|

| David at end of table, Sarah to his right, in black cap. |

David was able to forgive.

Speaking of his mother: “I still speak to her. I still love her.” His parents had eventually divorced, his mother

at long last admitted to her lesbianism, and his father remarried. David forgives his father, too. “Stitches

wasn’t a critique of the medical community. He didn’t know then what radiation could do. It was an accepted procedure

at that time, a standard practice for ‘curing’ all sorts of things. I was just recording what happened to me.”

The memoir is presented

without great affect, and David affirms that was intentional. When events are so horrific, words can get in the way. A skillfully

rendered drawing can say much more.

He adds: “Art didn’t

save me. Psychoanalysis did.” In Stitches, his therapist is drawn as a large rabbit with piercing eyes.

As the growing boy begins to rebel, he is taken to therapy, and once he stops resisting that process, he finds the first

person who truly seems to care about what happens to him.

Today, he beams—now,

he is a happy person. David lists off his blessings without hesitation: psychoanalysis, that first purging and lifeline; a

first bad marriage that lasted 12 years—“she wasn’t a bad person, it was just a bad match”—that

taught him many valuable lessons; a great second marriage with his best friend; blissful work; great friends; and now, this

book.

Our dessert dishes are empty.

Blueberries with whipped cream are but a stain at the bottom of our bowls. David’s childhood seems now but a stain at

the bottom of his life, even as he soars on to his next project, a quiet and peaceful life in the country, a loving partner

leaning on his arm.

A parting remark—as

much as therapy saved him from a path as a rebellious juvenile who would leave home at age 16, David attributes his therapist’s

success with turning his life around more to friendship than the rendering of a medical profession. Against all rules of therapy,

his therapist funded the troubled teen’s first apartment, did not spare a loving hug, and sometimes wept with him. The

two are still friends.

“There is a tremendous

amount of creativity in arts today.” When we reach out to help the troubled, David says, we must be careful in so much

drugging of people in pain. “We are leveling out a lot of creativity by drugging people. We need to honor a time of

silence.”

In Stitches, David

Small has honored his own survival story, purging pain, rage, the betrayal of those to whom he looked for love and support. A

finalist for the National Book Award in 2009, the graphic memoir has resonated with many, no doubt finding bits and pieces

of their own suffering, expressing their own silenced rage, perhaps to find voice in other forms of their own artistic expression.

|

| Book Maven poet, Elaine Seaman, chats with David as our luncheon concludes. |

|

|

To learn more about David Small, visit his Web Site.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|