|

|

|

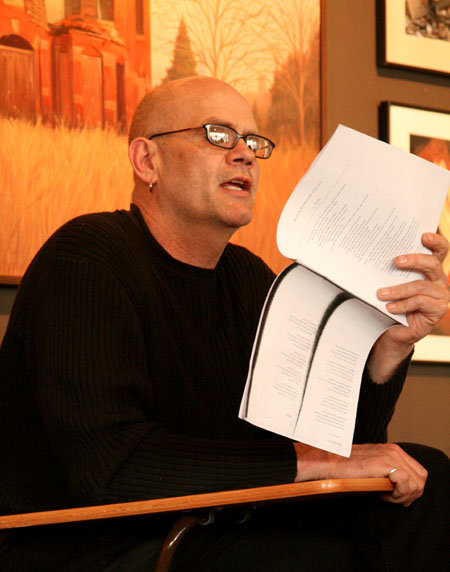

Derick Burleson's first book, Ejo: Poems, Rwanda 1991-94 won the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry. His second, Never Night, published by Marick Press, is reviewed here. His poems have appeared in The Georgia Review, The Kenyon Review, The Paris Review

and Poetry, among other journals. A recipient of a 1999 National Endowment for the

Arts Fellowship in Poetry, Burleson teaches in the MFA program in Creative Writing at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks and

lives in Two Rivers, Alaska.

|

| Derick Burleson |

|

|

|

|

| Derick and his horse, Magic |

The

Smoking Poet: Welcome

to The Smoking Poet,

Derick. Are you a born poet or reborn in poetry?

Derick

Burleson: I grew

up in the small wheat farming community of Cherokee, Oklahoma, where the idea of being a poet seemed to belong to another

galaxy. And this was true for me until I was a sophomore in high school and the homework assignment was to read John Keats’

“Ode on a Grecian Urn.” When the teacher asked what we thought of the poem the next day in class, I had an out-of-body experience in which

I raved about the goodness of the poem, and I think I shouted “truth” and “beauty” a lot. I have no

idea what I said, but when I came back to myself, the teacher and the 20 other students

I’d started kindergarten with and would graduate with a few years later were all staring at me open-mouthed as

if, indeed, I had just arrived from another galaxy. I had. I had deeply experienced the power of the language/thought/despair/longing

Keats captured late in his young poetic life, and they had not. Not in the same way. Not like that. Poetry has been a constant

with me ever since. I want to write poetry because I read poetry then, and because I read poetry now.

TSP: You live in a place of wild beauty—Alaska.

And you have lived in a great many other very diverse places. How much and in what ways does your environment interact with

and color your poetry? Not just in its geography but also in its culture and people?

Derick: Alaska is beautiful in the sense Keats

was getting at in his depiction of the urn – eternal beauty and truth. But I’ve been deeply affected by every

place I’ve lived: Cherokee and Stillwater, Oklahoma; Manhattan and Kansas City, Kansas; Butare and Ruhengeri, Rwanda,

Africa; Missoula, Montana; Houston, Texas; Ester, Fairbanks and Two Rivers Alaska. And all the many places I’ve visited

in between. Place becomes a part of us on a molecular level, the air we breathe, the food we eat, water we drink, words we

hear and say. The people we meet, the ways people do the things people do. And great poetry, I think, reflects that human

situation across the space-time continuum. All these places are places of great natural beauty, each in its own way: a concreted

Houston Bayou where a night heron fished to Alaska where I have to dodge moose sometimes on the way to school. Alaska is spectacular

in its wild way, though—the farthest you can go and still arrive, home to the nation’s tallest mountain.

TSP: You have also lived in Rwanda, Central

Africa. Tell us about that experience and about your first poetry collection, Ejo, winner of the 2000 Felix Pollak

Prize in Poetry. Tell us about the teaching, about being of service as a Peace Corps volunteer, why these things drew you,

how they changed you, how they touched the poet in you.

Derick: Rwanda is another place of incredible

beauty and wonderful people, with a more than 500 year history in which poetry plays a crucial role in culture. I taught at

the National University of Rwanda at both the Butare and the Ruhengeri campuses and worked with great students and colleagues.

I loved living there. All of this made the genocide which began in 1994, a year after I’d left the country, so unbelievable

to me. It’s one of the worst genocides the planet has yet endured. I wrote Ejo as a memorial to all the people I knew

who were murdered.

TSP: And then you lived in Texas, taught and

managing editor-ed Gulf Coast …

Derick: I attended the University of Houston where

I got a PhD in Creative Writing and literature and had the chance to work with some fantastic teachers: Mark Doty, Edward

Hirsch, Richard Howard and Adam Zagajewski, among them. It was a formative experience for me as a poet, student, teacher,

and as an editor. Gulf

Coast has since become one of the best literary journals in the country, I think, and it was incredible privilege

to be a part of that evolution.

TSP: Have you found home?

Derick: I’ve lived in Alaska for a decade

now, longer than anywhere I’ve ever lived with the exception of where I grew up in Oklahoma. And I still feel like I’ve

just arrived. I live in Two Rivers, 20 miles from campus in Fairbanks with a horse, 34 chickens, a dog, a cat, two goldfish,

a huge garden, and my seven-year-old daughter, Mirabel. We either grow, catch or gather most of what we eat: wild red salmon,

fresh greens and carrots from the garden, wild blueberry crumble is frequent late July dinner. Our woodstove keeps our house

cozy at even 40 below zero.

|

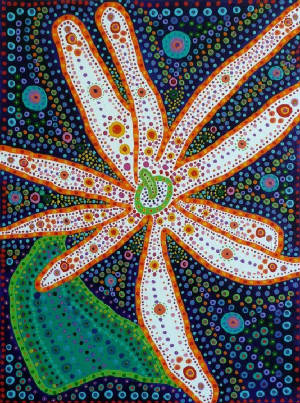

| Art by Derick Burleson |

TSP: You have taught and are currently teaching

creative writing—now at University of Alaska Fairbanks, and in the low-residency program at the University of Alaska

Anchorage. What is your philosophy on teaching literary artistry? What can one teach and what cannot be taught?

Derick: I feel really lucky to have the job I

do. How many people on the planet get paid to do something they truly love? My job is to read and write and talk about poetry

all day. Incredible! I try to share my own practice with my students, and I believe

that before you can hope to be a poet, you have to read as much poetry as you can possibly stuff into your body and continue

to do so until you die. Reading poetry has to be a part of your process. And writing has to be a part of that process, of

finding what you have to say and show that is both univeral and unique. This involves what is called work. Luck is also involved.

But you’ll never have the chance to attain what you hope to unless you’re willing to work.

TSP: Why poetry and not prose, or for that

matter, visual arts or … skipping stones across the water? What does this genre in particular do for you?

Derick: I do work in those other genres as well.

I’m an especially avid stone skipper. And painting has been an especially obsessive activity for me lately, and a lot

of fun, too. You can check out some images at derickburleson.blogspot.com. But poetry has always been my first genre, and

always will be because of that moment with Keats. And because the line is its basic unit. We call poetry ‘verse,’

meaning ‘to turn.’ The line allows motion, a building of expectation, a fulfilling of that expectation, or an

overturning of it, all with language and sound and symbol. For whatever reason we decide to turn before we reach the edge

of the page is a crucial element of the poem, and one of the most important things that keeps it ever fresh and vibrant for

me. (The decision not

to turn before the margin, or to write beyond it can be powerful as well.) Both poetry and painting are ancient art forms

– as is skipping stones – and it’s an honor for me to have the opportunity to participate and engage human

activities of “making” that have been around a long, long time, ever since we invented paint and language.

|

| Fishing in Alaska |

TSP: Never Night has a quality of an open eye or lens, focusing out to the infinite, then back again on the miniscule, nearly invisible.

You make us see. Talk to us about your vision, your inner eye, and what you want your reader to see.

Derick: This is a way of seeing I learned from

Elizabeth Bishop. In “Sandpiper,” for example, we begin with the infinite roaring of the sea along the beach,

and by the end of the poem we’re staring at grain of sand the color of amethyst. So is the sandpiper itself, a bird

which has become a stand-in for Bishop and her way of negotiating, engaging and seeing the world. So many of her poems manage

these huge shifts in perspective. Szymborska is another poet also especially adept at these momentous zoom in and outs. In

Never Night,

I was trying to have a conversation with Bishop, back across time and space, through the eternal medium of poetry, trying

on her way of seeing, from Key West to Alaska and beyond. She’s an important tutelary figure for my poetry, and –

as my students would tell you – in my teaching. And when you begin to read seriously in poetry, the ways of seeing your

elders have taught you become incredibly important to the craft and to the way you walk and what you see.

TSP:

The poem, “Late Valentines,” is probably the most moving, heart-shattering love poem I’ve ever read.

Can one be a poet without love? Indeed, this collection concludes with the lines: “The only reason I exist is/because

you love me.” On topics such as love and death, those biggies, it can be nearly impossible not to be swamped by cliché.

How do you avoid that? Okay, that’s probably a rhetorical question … you just do, and that’s the magic and

mystery of your poetry …

Derick: Thank you for liking my poem! Love, and

the loss of the beloved to inevitable death, is one of poetry’s eternal themes, and inevitably so, because what can

move us as crucially in our lives, turn emotion so physical feeling as love and the loss of love? I’m also very fond

of the sonnet, a very durable and vibrant form. I’m always astounded at how much can be packed inside a 14-line room,

inside a form that since it came into English has invoked and contained great poetry and still does on a regular. Love and

Death are clichés. Everybody gets to experience them. And, yet, like birth, each love, each death is unique. Poetry should

try to capture the essence of the universal in all its varied forms, I think, and it has. It continues to. It survives.

TSP: We always love to ask about process, because

it does vary so from writer to writer, poet to poet. Where is that starting point for you? When do you know you must toss

aside the pen? Do you write longhand? On napkins and beer bottle labels, or do you have a set aside sacred space?

Derick: I call my process “Butt in Chair.”

As in, put your butt in the chair and write. “Inspiration” doesn’t happen for me just walking around. I

have to be reading well to be writing well, and to be writing well, I also have to be writing poorly sometimes. Much of what

goes onto the the computer never comes out again. I write random lines in my

journal, and parts of poems, and drafts of poems, and class notes, and snarky comments from university committee meetings,

and lots and lots of doodles. But the poem doesn’t seem to really begin to happen for me until my hands are on the keyboard

for hours at a stretch, when time turns to no time. I do have a space, a chair, a small desk, a laptop. As I look out the

window now, at midnight, there’s still enough light to see the spruce and birch trees around my house. If I look up

on the wall, I see images by Van Gogh and Dali, Monet and Hopper, Pollock and Susan Rothenberg, and by my daughter Mirabel.

And portraits of six poets: John Keats, Elizabeth Bishop, W.B. Yeats, Sylvia Plath, W.H. Auden and Wallace Stevens. And a

bookmark pinned to the wall of Smokey the Bear with the caption, “If not you, who?”

TSP: What next, Derick? What is in the works

and what is in dream phase?

Derick: I have two collections I’m honing

now. The first is Melt,

a book-length lyric meditation on the conjunction of erotic desire and loss and global warming, the effects of which we’re

beginning to witness firsthand here in the sub-arctic. The second is called Use, a more experimental book-length set of short lyrics constructed from

a list of “the 600 most commonly used words in English” that I found in my daughter’s kindergarten classroom.

I found that list captivating, and quite frightening, filled with implications of ownership and gender and imperialism The

words are listed in order of which is most commonly used. “Water” comes only four places ahead on the list than

“oil,” for example. “War” appears in the 400s while “love” doesn’t show until near

the end. I built the poem out of the list, and the list is what the book’s about. I’m working on new poems now,

messing around, looking for the next book.

TSP: We can’t wait. Remember us when

it is time to review your next book. Our review of Never Night can be viewed at Zinta Reviews. Thank you so much for talking to us, and if we want to keep tabs and learn more, where shall we find you?

Derick: Right here, in Two Rivers, Alaska. Just

turn right off Breeze and you’re practically here. It’s not at all hard to find, but it is a long trip for most

folks.

Learn

more about Derick Burleson:

www.marickpress.com/index.php?/never-night

www.uwpress.wisc.edu/books/3363.htm

www.derickburleson.blogspot.com

|

| Art of Derick Burleson |

|

| Who caught who? Derick and 75-pound lingcod |

From Melt by Derick Burleson

The fish itself was water made flesh

silver scales striking black spots down

the back black inside the mouth hooked

teeth to seize blushing to color now she

was in the river headed upstream

through the eddies and pools through

riffles and maelstroms she was bound

for a clear creek with a gravel bed.

But our net brought her close and we

touched her our hands slipped along

her slime and we took rocks and beat

her on the head to stun her then slit

her open and the roe spilled out twin

sacks the color of sliced tangerine

full of thousands of potential kings.

She was the river the ocean the river

made solid and I slit her from anus

to throat I cut around her arterial

gills and pulled her heart out still

beating. Her flesh oily the pale flame

of her twin skeins of roe. Oh she

never made it upstream and her body

became our bodies charred and oily

from the fire. We ate her skin her

flesh. We sucked the bones clean.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|