|

|

| Parkers |

Barbecue with Kent

by Michael Brantley

We pull into the restaurant

parking lot on a late afternoon that looks more like a cold, bleak, Monday in February than a Friday afternoon in mid-September.

However, as we step out of my Honda Civic, we are met by a combination of drizzling rain and mugginess — a feeling that

a warm, wet blanket had been tossed around our necks. Summers in North Carolina do not yield easily to the next season.

The parking lot is a pockmarked

jumble of black asphalt with utility poles located in the most awkward of places. I haven’t visited this joint in a

long time, and I find myself wondering why anyone would place utility poles right in the middle of traffic lanes and parking

spaces. Then I remember that this highway has changed and meandered a lot since its first day of business, shortly after the

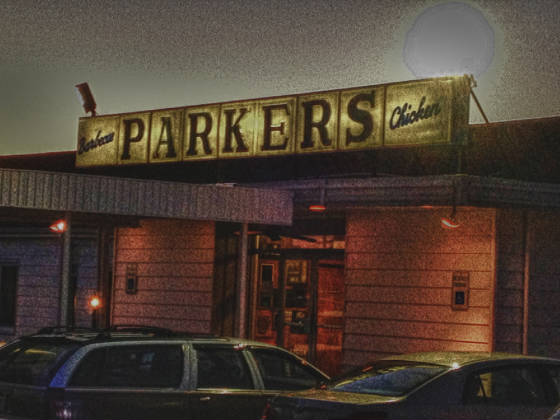

end of World War II. The restaurant itself still appears as it did when I was a child — a large, long, white building

with a single sign mounted on the roof displaying the name of the original proprietor in blue-black letters: Parker’s

Barbecue.

A funny thing about Parker’s

is how the parking lot has its own neatly divided demographics. In front of the main entrance, where the dine-in area is located,

the spaces are filled with minivans, station wagons, immaculate pickup trucks and long, American-made sedans — the crowd

made up of retirees and middle-aged farmers, mostly. Those are the folks who roll in starting at 4:30 and thin out over the

next two hours. The takeout parks, around to the side, are a bit more egalaterian:

RVs, rust buckets, giant, muddy pickup trucks and small foreign-made hatchbacks — these drivers love the same food but

lack either the means or the time to sit down for a meal inside.

The name Parker’s

Barbecue says it all. For folks from eastern North Carolina, no other qualifier is needed. They know exactly what is cooked,

served and packaged at a frenetic pace seven days a week, all day long — barbecue. Barbecue is not a verb, it is not

a noun that needs an adjective denoting what animal (for the record, pig) the meat comes from, it is not an event. Its authenticity

is regional, no different than gumbo is to Louisiana, brisket is to Texas, cheese steaks are to Philadelphia or bagels are

to New York City.

Parker’s, on a blighted

stretch of U.S. Highway 301 in Wilson, has changed little in the generations that have passed since they it opened the doors,

shortly after World War II. Despite living so close to such fine establishments, our family of five rarely dines on barbecue.

I grew up on the stuff – finely chopped pork shoulder, seasoned with vinegar and crushed red pepper; finely-chopped

slaw made with a heavy hand of celery salt, mustard and sugar; Brunswick stew; boiled white potatoes; cornbread sticks; and

of course, hushpuppies. Fried chicken to rival the best anyone’s mama has put on the table, is usually a “side

dish” as is barbecued chicken, cooked right alongside the pig over either charcoal or wood. The menu is as plain as

the building. It should also be noted, from my personal experience, that the sweeter the ice tea is at a barbecue joint is

directly related to how good the food will be. A person served unsweetened tea should place an appropriate amount of money

on the table to cover the cost of the drinks and leave immediately. The tea at Parker’s is very sweet.

When I was a child in

the late 1970s and early 1980s, we got most of our food off the family farm. For

the occasional treat, and to give my mama a break from her usual routine of cooking three meals a day, my parents would take

my brothers and sisters and me out for a family meal at Parker’s. We’d sit at long tables covered in white butcher’s

paper, and eat food off brown plastic cafeteria-style plates loaded with barbecue, and the trimmings. My siblings always got

a combination, with fried chicken and barbecue sharing the meat space on the plate, along with potatoes and slaw, the natural

companion to pork. For me, barbecue was a delicacy, and I wasn’t about to sacrifice half my share for a drumstick; double

slaw and bread was all I needed for accompaniment, until I got older and developed a taste for Brunswick stew. Daddy’s

plate always seemed piled a little higher than the others, Mama’s a little more modest.

Young boys from the local

high schools or Atlantic Christian College waited the tables. Each was decked out in a white shirt, white pants, a white apron

and a white paper hat. Those boys practically ran from the kitchen to the tables, refilling drinks and doing all the bus work

themselves, clattering red tumblers, trays, chicken bones, napkins and silverware into big plastic tubs. A generation ago,

a single plate of more food than a normal adult should eat in one sitting could be had for a few dollars, just right for my

folk’s budget, which was strictly based on the cash in Daddy’s well-worn, black leather wallet.

My middle son, age six,

loves to go places he’s never been, especially if those places are somehow connected to my childhood. As we found a

parking space near the side entrance at Parker’s, between a well-worn dingy white Chevy custom van with blue pinstripes

and a massive black Z-71 pickup truck, I told him we’d be getting takeout, having just come from a rain-shortened youth

soccer practice.

He always peppers me with

questions, and today was no different. This section of Wilson is long past its heyday, now that I-95 has supplanted the old

highway as the major artery leading north-south, the halfway mark between New York and Florida. Highway 301 was once bustling

with neon-lit motels, restaurants, gas stations and the city fairgrounds across the street. Today, it looks like 1962 just

packed up one day and left. Kent wanted to know why everything looked so old and broken. The area is flat, and many of the

pine trees that added life and color were thinned first by Hurricane Floyd back in 1999 and then by two rounds of tornado

touchdowns in the past three years. It is hard to tell if some of the single-floor “motor courts” are still open.

One is now occupied by a Chinese restaurant with no cars on the lot at the dinner hour, just a lonely red OPEN sign on the

office door. Another seems to have a Mexican grocery and could possibly be apartments now, while the neighboring establishment

that looks right out of a postcard from Highway 66, seems seedy-looking enough to be doing trade of a different kind. Almost

all of the buildings need renovation or demolition, and are unlikely to get either.

We worked our way towards

the takeout annex, which is tucked around the side of the restaurant, away from the high traffic goings-on at the front door

to the dining area. Tall, skinny and athletic, my orange-haired boy — he doesn’t like to be called a redhead —

usually sticks close to me, but he seemed tentative. The backside of Parker’s doesn’t have much curb appeal and

old, run down storage buildings with flaking paint are surrounded by knee-high grass and weeds. Crates, pallets, delivery

boxes and miscellaneous debris lay scattered in the back of the building. Kent asks if I am sure we’re going the right

way. We walk up an old-style ramp with indoor-outdoor carpeting, open the screen door and step back in time.

I guess my generation,

the one they call X, started the breakup with restaurants like Parker’s. Diets have changed. Farmers and blue collar

workers had long days of physical labor to help offset what would be considered a high-calorie, high-cholesterol lunch today.

Travelers and buyers from what was once the world’s largest tobacco market knew the places they could count on for good,

cheap food to get them through the day.

Maybe barbecue was the

the forerunner to today’s fast food, only it doesn’t come packed with artificial fillers and loaded with additives

and preservatives.

Where there were once

barbecue and hamburger places on every street corner of towns across the eastern part of the state, they’ve now been

replaced with Mexican and Chinese restaurants. These places provide no healthier alternative for the 18-to-35-year-old working

professionals, they are just trendier. There has been essentially a patron-cide for an entire segment of the population. General

Tso’s chicken or Carnitas, I suspect, will keep heart bypass folks just as busy in the coming years as the places serving

grilled pig meat doused with vinegar.

We walk across an old,

but clean gray-painted concrete floor and stand in a line that is nearly ten deep with customers, cooled by a single, ancient

ceiling fan. A few stray flies work the room. I groan to myself, fearing a long

wait and a soon-to-be-impatient first grader. But two young men, probably still in their teens, work the register like pros.

They turn their ears towards the customer, scribble orders on a stubbed order pad, ring up totals, collect cash, give change

and pass the orders to a waiting crew member. Another dozen boys work like a well-greased machine in the background, tightly

packing barbecue, vegetables and trimmings into plastic containers, and then double-bagging each order. McDonald’s wishes

they could turn orders that fast. The workers still wear the white aprons, shirts and paper hats.

The line moves quickly

and suddenly I realize I have no idea what I’m going to order and how much of it I need. The wall menu is the type you

see at high school concession stands, featuring a soft drink company’s logo and sporting blue plastic snap-on letters.

I’m lost on quantities. Kent tells me to be sure to get him some cornsticks, he would really like one, he’s never

had one, and by the way, what are they? He points out we should get chicken as well, as he watches a worker use metal tongs

to dump large crispy wings and legs, one after another into a large bag, until it is almost full, then he tops it with cornsticks.

Kent is practically licking his lips.

There is no place for

debit cards in this world, so I check the cash in my wallet and order accordingly. My transaction and the filling of my order

are almost instantaneous, and the bag is warm to the touch. We excuse ourselves through the mass of people who have entered

the building since we arrived and emerge from the past to find the rain has stopped, and in its place a cool breeze greets

us. Kent says he hopes I got enough food, he’s starving.

We spend most of the 30-minute,

back roads drive home talking about what Parker’s was like when I was a kid. I told him about how his aunts and uncles,

all a decade or more my senior, laughed and cut-up at the table, while his Mammy answered my endless questions, like

I do for him now. I told him how good the food was then, and how we only went out to eat a few times a year and that it was

usually a big deal, a much different lifestyle than his. He asked why we don’t ever go now, and that sometime, he’d

like to go in and sit down like I used to do. I’m tempted to dig into the bag and fish out two cornsticks — which

are cigar-shaped, thin strips of cornmeal, deep fried to a crispy crust— and pass one to Kent to try. I decided against

it. The aroma of all the good things we’ll have for supper heightens our anticipation, and I wonder if my kids will

enjoy the food the way I did at their age. My question is answered shortly after

we walk into the kitchen at home. His older sister and younger brother meet us at the counter, my wife trailing behind, all

drawn quickly to the aroma of grilled pork, pepper, cornsticks, chicken and stew.

We have plastic trays,

but the not the generic variety of my childhood, these feature cartoon characters and superheroes. After bouncing impatiently

in their chairs as the food is piled on, the next thirty minutes is silent except for the smacking and finger-licking and

calls for more. The taste was just as I remembered it: the cool sweetness of the slaw a perfect counterpunch to the saltiness

of the vinegar drenched meat; the tanginess of the rich, spicy, tomato-based Brunswick stew, made for dipping the crunchy

slabs of cornmeal into. It took two more well-savored meals to clean up the leftover barbecue, slaw and Brunswick stew. The

chicken and cornsticks never had a chance.

Food is a tie that binds us, and regional foods are at risk for losing their authenticity at the hands of

a society demanding fast, bland, boring sameness. When locals who have moved away come back to visit, a barbecue place is

one of their main priorities— either for a meal or to take some back home, to work those great memories back into their

lives.

By contrast, we could

have chopped pork just about anytime based on price and proximity and rarely do. I realized after that night of Parker’s

that I have become one of the people I complain about — those who have abandoned the institutions that ought to be saved.

Places like Parker’s, places with personalities, define and distinguish communities and regions. Hectic lifestyles and

changing interests took us down other pathways, much the way childhood buddies drift apart. My complicity in abandoning an

old family favorite, albeit unintentional, makes me feel somewhat hypocritical. After all, my future grandchildren ought not

be deprived of a place so special and nostalgic in my memory, and now, just maybe, also in Kent’s.

Michael Brantley

is a freelance writer and photographer. He teaches as an English adjunct instructor at Barton College and Campbell University

in North Carolina. Michael has an MA in English from East Carolina University and is currently pursuing an MFA at Queens University.

His work has most recently been featured in Prime Number Magazine and The Cobalt Review.

|

|