|

|

|

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

More

reviews coming soon …

|

|

|

Reframing Change: How to Deal with Workplace Dynamics, Influence Others, and Bring People Together

to Initiate Positive Change by Jean Kantambu Latting and V. Jean Ramsey

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

· Hardcover: 226 pages

· Publisher: Praeger, 2009

· Price: $34.95

· ISBN-10: 0313381240

· ISBN-13: 978-0313381249

So many how-to books out there today—how to be better at this or that, how to learn this or that skill. One would

think by now humankind would have achieved perfection. No argument here: we are far from perfect, and we have a lot to learn.

Or, if at heart we all pretty much know what is missing, what we need to do—let’s just call it the Golden Rule

of treating others as we would wish to be treated, delivered in countless variations—it is a message that bears repeating

an unlimited number of times and perhaps in an unlimited number of perspectives. After all, the same message delivered another

way may be just what any one of us may need, and the moment in time that any one of us is truly receptive to that message

is constantly in flux, too.

So, yes, we have here another book about how to be better human beings and how to get along better with each other

in the workplace. And I’m going to recommend this one. Not only for the workplace, but for anyplace, because I found

its approach and conclusions are just as relevant to our personal lives as our work lives. Indeed, I had to wonder in reading

it why the authors would limit its scope to workplace only. This is valuable stuff, wherever you might wish to have more fruitful

interactions for with your fellow man and woman. It could even be read as sound parenting advice.

Authors

Jean Kantambu Latting and V. Jean Ramsey are equipped to speak with authority. Latting is an organizational consultant and

co-director of Leading Consciously. She is professor emeritus of leadership and change in the graduate school of social work,

University of Houston in Texas. Ramsey is also a co-director of Leading Consciously, and is professor emeritus of management

at Texas Southern University.

The

book reads something like talk therapy, bringing the reader into a workshop or seminar of others who are working to handle

various workplace obstacles and challenges. Each chapter is filled with transcripts of discussions and conversations with

groups and individuals, handling situations that the reader will recognize as similar to one’s own. These are common

issues cropping up anywhere where people work together—the dynamics of diverse personalities and work styles, intertwined

with personal problems and issues that seep into our work lives. Lest this devolve into too much group talk, however, short

paragraphs called “Curious About the Research?” are regularly interspersed, bringing the science to the talk.

The research cites studies and substantiating figures, often piquing curiosity to extend one’s reading to learn more.

The

best advice is simple advice, not to be confused with easy-to-take advice. Thus, I’m sure, the need for the same basic

messages to be conveyed to us over and over again. The approach taken by these authors is wonderfully simple and on target.

The transcribed discussions unfold as surely do the questions and arguments in most readers’ minds. What do you mean, the change has to begin with me? Yes, but he started it! It’s obvious that I am right, and

she is wrong. And so on. The authors have obviously heard them all, and here they all are.

The

premise of the steps for positive change suggested in this book is that the reader is a person of integrity. Integrity is

defined as a pattern of behavior that is consistent with one’s values. Discord, guilt, anger, defensiveness, all that

bag of negativity in human interaction, opens up whenever we act in discord with our values. There’s the hint we should

never ignore: sense any of these cropping up and look to realign your behavior with your values. Time to make conscious change.

“Demanding that others change often increases resistance and ends up pitting

people against one another. Self-change in more likely to plant seeds leading to broader-based change in the work setting—change

that may be more sustainable. No matter how powerless you feel in a given situation, you have choices. The ability to choose

is a major source of your power to make a difference.”

(pg.8)

Assuming

we readers are a nice sort, interesting and willing to be persons of integrity, the book prescribes clear steps on how to

live a life of integrity, in or out of the workplace. Testing assumptions is a good place to start. Even when we think we

are being rational and clear, we may not be aware of just how many prejudices and biases and assumptions are entering into

our thinking. For instance, a great many of us like to think that we are above average. If that were indeed so, averages would

be quite different. We can’t all be above average in all that we do. It’s a good place to start: strip away the

ego for a moment and examine the face in the mirror. Right may not always be exclusively on our side. Remember that Golden

Rule, that most ancient of self-help mantras? Consider the other side may have a valid viewpoint, too. Another human tendency

is to fill in the blanks, the unknowns, with our own assumptions, and this is where truth often becomes degraded.

Putting

yourself in another’s shoes is always a good idea. How to do that, the authors suggest, is by “being in the question.”

Assumptions fade when we open ourselves to ask questions rather than make hard and fast statements.

“Being in the question is wondering what things mean instead of assuming

you already know. It involves treating your first thought as a hypothesis rather than a statement of truth … As such,

it takes more work—and humility—than being in the answer. It requires searching for alternative explanations for

others’ behavior.” (pg. 22)

Among

our frequent assumptions are that others have the same background as we do. Being aware of cultural differences is essential

in an ever more tightly knit global community. The authors remind us that cultural differences extend beyond national or ethnic

origin, but involve also social group memberships that may result from our biology, gender, age, sexual orientation, hierarchy,

economic class, occupation, geographic location, and many other factors.

Clearing

emotions is the next step. While the authors warn against suppressing emotions—this can never lead to positive change

or understanding—they also warn that thinking through a cloud of emotions can fog our path to resolving misunderstandings.

Bringing up, thoroughly examining, then setting aside our emotions are steps that must be taken first; there are no shortcuts.

Understanding and facing an emotion is not the same as acting on it. In fact, understanding and facing our emotions first

and foremost is the only sure way to prevent acting out.

Having

cleaned house, we can begin to build effective relationships. Powerful listening is an important building block for intimacy

and the ability to work together as a team (can you see why I think this book would work equally well outside of the workplace?).

When one listens, it is crucial to not substitute one’s own version of events, to not put down the other person or immediately

toss aside their viewpoint without consideration, or to downplay the other’s perspective. Positive feedback opens people

up, and we can offer it—even when we are in disagreement—in many ways. We give feedback with our body language,

with the tone of our voice, with our lack of focus. We shut others down when we are sarcastic or critical. We also shut down

open communication when we use humor that is hurtful to others.

When

we are in a situation where change is needed, powerful listening lays the groundwork. “Three

things are required for individuals to hear your feedback and be willing to change. First, they must believe change is necessary.

Second, they must believe it is an improvement … Third, they must believe they’re capable of making the change.”

(pg. 80)

Change

cannot be forced. It is a choice that we must each make for ourselves, and that we must feel we are freely choosing for ourselves.

Bridging

differences is then the next step, and here the authors stress how power, or being dominant in a relationship or group, causes

a kind of blindness, or tunnel vision. Diversity is crucial, but the authors clarify: “Diversity

alone is insufficient. Simply adding differences to your group or organization and then pretending those differences don’t

exist won’t get the job done … people must feel their contributions matter. Yes, diversity can bring conflict

and tension, but it can also be productive.” (pg. 126)

Research

shows that “bringing people with different perspectives together often results

in increased creativity, innovation, and performance. The key is in learning how to manage the conflict and to learn from

one another.” (pg. 127)

When

encountering differences, we sometimes make mistakes, act badly, hurt others. We may discriminate against others different

than ourselves, or even exploit those over whom we are dominant, or in a position of power. At these times, we are in discord

with integrity, i.e., we are not living according to our values. Guilt can be a powerful force for change, alerting us that

we are doing wrong and that we must make amends, take the steps necessary to resolve the wrong.

An

especially interesting chapter addresses self-deception. Just as it is human nature to think of ourselves as often somehow

better or smarter, more valid, than others, it can also be a human weakness to seek blame and so seek out rationalizations

for ourselves when we have done wrong. Self-betrayal, the authors write, is when we act outside our integrity, against our

own values, and “then, to justify your actions, you figure out reasons to magnify

the other person’s faults and your own virtues. In so doing, you deceive yourself.” (pg. 150)

Rather

than blame-shifting to ease our own discomfort, we must look honestly at ourselves, but also at the other, doing our best

to understand why they are as they are, even if that state is abhorrent to us. Trying to understand another’s perspective,

the authors stress, is not the same as agreeing with them. Everyone wants to be heard, even the wrongdoer, and in being heard,

we have actually allowed the first step toward change. (The authors here also make an important distinction for those who

are in battering or abusive relationships, in or out of the workplace, as not being responsible for the bad behavior of the

other.)

“People do not resist change, they resist being changed. People want to

change on their own terms, not someone else’s.” (pg.

173)

Perhaps

this book’s most valuable statement is that the commonly held “wisdom” that people resist change is actually

constantly disproved when we take a look around us. Life is, by its very definition, to be in a state of constant and unabated

change. People, workplace environments, relationships of all kinds, actually thrive on change. Think of change as growth,

and you understand that change is necessary for any living thing. We must only respect what it is that makes us afraid, causes

resistance … often just another name for being protective … and we unleash all manner of positive change.

This,

then, is that core idea of “reframing change.” It may not always be easy, but it is often necessary and often

good. We feel a deep need for change when our environment becomes uncomfortable, and discomfort always has reason. Recognizing

“small wins” along the way, giving ourselves and others positive feedback, being conscious and emphatic to our

differences, all lead to achieving a better and more productive workplace.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Imposter? How a Juvenile Criminal

Succeeded in Business and Life by Kip Kreiling

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

·

Paperback: 312 pages

·

Publisher: Transformation Help Press, 2009

·

Price: $17.77

·

ISBN-10: 0615320554

·

ISBN-13: 978-0615320557

When the author contacted

me about doing a review of his book, I very nearly said no. I get several review requests per week, so I have been forced

to get choosier about the review copies I accept. But I took a closer look at the book description and changed my mind. We

don’t have nearly enough books that talk honestly about the shortcomings of our juvenile justice system. Perhaps Kreiling

had something new and important to add?

I was a little put off by

the large print of the book when my copy arrived. It makes the book bulkier than it need be, and implies a readership it probably

doesn’t have—the elderly? The very young?

I started to read, and large

print was forgotten, as I fell into the story. This was a heck of a story. One with which, unfortunately, I was all too familiar

from my own experiences, raising my son as a single mother. Those preteen and teen years can be so very difficult for boys

and young men growing up without good, strong male role models, and having a father present doesn’t in and of itself

fill that gap. It depends on the type of father. But I could relate to young Kip’s mother painfully well, the heartbreak

of watching a son struggle to find his place in a world that makes a molehill of a youthful mistake quickly turn into a mountain

of trouble. What should be a “teaching moment” or a wake-up call often gets turned into a downward spiral by a

juvenile justice system that is often predatory and punitive rather than caring and rehabilitative.

With Kreiling’s misadventures

with drug use; gangs or kids simply gone wild; with the idiocy of the current juvenile justice system—“They were

turning me into a harder criminal than I already was.” (page 35)—and an educational system that has been broken

for a long time; with a society in general that treats our youth as second or even last priority; a foster system that started

as a good idea but is now more infamous for abuse cases than rescue stories; we are all in trouble. This cannot go on.

I read with excitement,

because Kreiling was telling a story that needs to be told. I’m glad to see he is an enthused marketer as well, doing

everything he can to promote his book. Good. I have visions of this book being passed around juvenile delinquent homes and

youth prisons, even adult prisons, with its basic message of hope: everyone can change. Indeed, perhaps that is the thought

behind the large print, because those who languish in prison more often than not come from backgrounds of poverty and little

to no education, so whatever can be done to make this easier to read is a good idea.

A better idea: another round

of editing that goes deep with cuts and brings the writing, which is not bad but not yet up to par, to the level this memoir

deserves. Personally, my suggestion would be to lose the eight principles of change and to simply write his story, tell it

like it was and how it is now. Write the memoir, skip the rest. Let the story tell its own lessons, rather than inserting

an artificial listing of principles, or morals, at the finish of most chapters. After all, none of the lessons are particularly

memorable, and certainly nothing we haven’t heard before. Principles of change such as (paraphrased)—change your

environment and you will change yourself; don’t plan for failure; choose your friends carefully because you will mimic

their behavior; get disciplined in pursuing your dreams, and so on, appear in countless variations in a thousand self-help

books and many are already a part of the commonly known 12-step programs that, frankly, do it better.

When Kreiling wrote about

his own life, I was mesmerized. This was honest, raw, ugly, real. This was good and inspirational storytelling, with plenty

of conflict and obstacles to be overcome, a hero that kept falling but still had something of integrity buried deep in him

right from the start, keeping the reader interested and rooting for him to survive. One only had to look closely enough, and

through caring eyes, to see the potential and root for it.

While some of Kreiling’s

intellectual explorations are mildly interesting, they, too, tended to distract from the meat of a great story. I had to think

of one of the most powerful books I’ve ever read: Monster : The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member by Sanyika Shakur, who today works to end gang violence. Had Kreiling

stuck to his memoir, his good message would surely have more power and less of a didactic tone. Instead, Kreiling veers into

side stories about Abraham Lincoln and Ben Franklin and Ayn Rand and young Gisela, a brainwashed Communist who sees the light

by spending time with a tour group of boys (including Kreiling) from the free West. These tour group boys understand that

they will not change Gisela by preaching to her. They instinctively understand that she will learn in a more meaningful way

simply my observing what freedom looks like in her peers from the free world. Kreiling would do well to apply the same wisdom

to his book.

Mind you, those side stories

are interesting, and I could relate. I, too, traveled behind the Iron Curtain as a young woman. I, too, was drawn to Ayn Rand’s

philosophy, and I even went through some of the same internal debates as Kreiling, wondering how and if Rand’s objectivism

could fit with Christianity. I suspect if I ever met Kreiling, we’d have a heck of a lot to talk about and a great deal

of experiences on which to compare notes. Yet crowding all these tangents into one book is just that, overcrowding, and dilutes

from the purity of his message.

This message is too important

to miss. Kreiling has all the requirements to be the one to tell it. He has been to those darkest of places. He has hit despair,

seen the insides of prisons, and he has known what it means to sink into and to beat an addiction and to relapse and have

to beat it again. He knows what it means to betray and be betrayed. And there is no more powerful storyteller than he who

knows and tells it from the heart.

Kreiling has lots of heart.

Or call it conscience. It is his heart and his conscience—and a keen intelligence that makes itself known even when

still uneducated—that save him and save this book. Kreiling has led a remarkable life. Today a successful businessman,

husband and father, he has proven that change is possible. He has shown that any addiction can be overcome. These are the

makings of a great story. Cleaning away the frill and the fuss, this great story could really touch many hungry hearts and

minds, those like his, despairing to keep hope alive.

A product of our broken urban society, Kip Kreiling was arrested 3 times before he was 10 years old

and 11 times before he was 14. When Kip was only 13 year old, he was taken out of 2 schools, a shopping mall, and a bank in

handcuffs. Because of his criminal activity as a youth, and the resulting chaos he brought into his life, Kip moved 34 times

from the young age of 11 to the age of 26. On average, he moved every 5 months for 15 years, in and out of jails, group homes,

and street shelters, while his mother and father moved less than 4 times each. Today, Kip is a Fortune 15 executive who has

had the opportunity to work with several of the world's most respected companies including Ford Motor, Hewlett Packard, Vodafone,

and the UnitedHealth Group. As of 2009, Kip has provided transformation and business leadership services for over 40 companies

in more than 20 industries. Between his corporate, consulting, educational, and speaking engagements, Kip has had the opportunity

to travel to nearly 200 cities in 21 countries on 4 continents. Kip earned his Bachelor of Science degree at Brigham Young

University and his MBA at Indiana University. Kip Kreiling is also the founder of the nonprofit foundation TransformationHelp.org.

The foundation is focused on improving the human condition through personal and organizational transformation, with a focus

on teaching transformation classes in prisons. Most important to him, Kip has been happily married for almost 20 years and

has five healthy children. For fun, Kip enjoys multiple activities in the mountains including boating, water and snow skiing,

camping, and hiking.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Storm Tide by Marge Piercy

and Ira Wood

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

·

Paperback: 320 pages

·

Publisher: Ballantine Books,

1999

·

Price: $12.95

·

ISBN-10: 0449001571

·

ISBN-13: 978-0449001578

I’ve

read many Marge Piercy books, novels and poetry (and, in general, lean more toward the latter), and reread several as I prepared

to do an interview with the author for the spring 2010 issue of The Smoking Poet. Her ability to produce is remarkable.

At this writing, she has produced 17 novels and 17 collections of poetry, and her range in genre is equally awe-inspiring.

Storm Tide, however, was the first I’d read in which Piercy collaborated

with her husband, writer Ira Wood. I was most intrigued as I settled in for a good Sunday read. Would I be able to distinguish

the two? Would their styles mesh or would the seams show?

The

novel opens with a chapter called, "David." It is written in first person, and the character is a young man, a baseball player

who didn’t quite make it in the big leagues, and so seems a bit confused at this point about who he is, what are his

other talents, how might he make himself useful in life. I assumed (correctly) that this was Wood writing. I had never read

his work before, but by end of the first page, I determined I would. He opens:

“When the winter was over and my nightmares had passed, when someone else’s mistakes

had become the subject of local gossip, I set out for the island. I made my way in increments, although the town was all of

eighteen miles square. To the bluff overlooking the tidal flats. Down the broken black road to the water’s edge. To

the bridge where her car was found, overturned like a turtle and buried in mud.”

Introduced

to David Greene, we then move to chapters titled Judith, and these are written by Piercy. Interestingly, these are not in

first, but in third person, giving the reader perhaps more intimacy with David, more distance from Judith. And the story does

seem to revolve more around David.

David

is attracted to the older Judith Silver, a very strong and independent, intellectual woman, a lawyer married to Gordon Stone.

Immediate comparisons come to mind to the autobiography I had just read by Piercy, Sleeping

with Cats, in which we learn that she was married when she met Wood, that her then husband condoned, even at times encouraged

her affair with Wood, who seem to have more confused feelings on the issue. In my review of the autobiography, I pointed out

that every work by an author is to some degree autobiographical, and so we see the similarities here, too. In fact, I found

it especially interesting reading the two books side by side.

Back

to the story: it is a weaving of several threads, coming together in this small Cape Cod town, where everyone knows everyone’s

business. We meet Johnny Lynch, a powerful local politician, corrupt and yet at times benevolent (if with ulterior motives),

entrenched in his place of leadership and not about to let go. Opposing his views on the town’s welfare, Judith Silver

and Gordon Stone nudge David into position to run for town selectman.

Adding

intrigue and complexity to this scenario is the evolving affair between Judith and David, the quickly spreading cancer that

ravages Gordon’s body, the arrival of the pinup style young woman, Crystal, who plays sweet and sexy, but is deep-down

damaged, if not occasionally malevolent, using her feminine wiles to manipulate David. Crystal is driven by her need to have

a man in her life, and she aims for David to fill that need. She has a young son, Laramie, whom she uses unabashedly to pull

on David's heart strings and tie him down with guilt trips and parental obligations. Whether because of his youth,

or simply that he is too easily seduced and led around by his anatomy, David becomes perfectly entrenched in Crystal’s

honey-sweet trap. Seeing this Achilles’ “heel” in his new political opponent, Johnny Lynch uses Crystal

against David to the very end, and to disastrous results for all, even the young boy.

The

book is a fast reader, a true page turner. The contrasts between characters are especially fascinating: Judith, the sharp

and smart, mature woman—and Crystal, the loopy pinup girl with nothing to offer but her body (and riddled with jealousy

over the older woman); David, the young baseball player turned politician with good intentions but capable of the most ghastly

mistakes—and Gordon, the dying man who has been there, done that, and is ready to pass his wife along almost like so

much property as he nears his final days. Indeed, that can be the most puzzling part. While Judith professes open relationships,

she quickly enough withdraws her favor from David when he grows too involved with Crystal. She explains it away as somehow

different when David protests that she, after all, is a married woman, but it is not convincing and difficult to follow her

logic. Everybody wants to be first to someone, including Judith. And then there’s Johnny, an old letch when it all comes

down to it, using Crystal at first for political strategies to spy on his opponent, but then deteriorating to being just one

more horny old toad who wants a piece of that. Here, tragedy truly unfolds.

Not

one of my favorite Piercy books, but all in all, in the top few. I enjoyed the interwoven stories and characters, the collaboration

between two writers—including the interview with the two at end of the book. Their work blended seamlessly, two masters

crafting their work into one, a shared success.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cowboy & Wills: A Love Story by Monica Holloway

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

·

Hardcover: 288 pages

·

Publisher: Simon Spotlight

Entertainment (October 6, 2009)

·

Price: $24.00

·

ISBN-10: 1416595031

·

ISBN-13: 978-1416595038

To

set the parameters of my review: I know next to nothing about autism. My knowledge of this disorder is limited to the anecdotal,

the various news items and studies that pass across our daily consciousness, this and that about autism being over diagnosed,

that it may be caused by something in our food, or by various childhood vaccinations, and other such. I won’t claim

to hold strong opinions on any of this, as it has not been an area of research or particular interest to me. I have a couple

of casual acquaintances with autistic children, both highly functional, and that’s it—that’s all I’ve

got.

For

this very reason—because I know so little about this diagnosis which children today alarmingly often seem to have attached

to them—I took on reading Monica Holloway’s Cowboy & Wills: A Love Story with particular interest. I wondered if autism might be something like ADHD, another diagnosis that seems difficult

to make. Indeed, my own son was diagnosed with it at one point in his childhood and early teen years, only to have the next

doctor cry “balderdash!” and the next one reverse that and the next one reverse that again. I eventually agreed

with the balderdash opinion. He does not, never did, have ADHD. Nor did he have any other number of diagnoses that various

doctors with an alphabet soup of credentials behind their names make. He was a teenager growing up without a father in a single-parent

home, and so he acted out his anger and confusion and fear of abandonment. He grew up, gained maturity and understanding,

and stopped acting out. End of story. So is this epidemic of autism anything like that? I don’t know, don’t claim

to know, but my curiosity was piqued.

I

was quickly drawn into Monica’s story about her young son, Wills.

“Wills Price is exceptional.

“If you happen to meet him walking down our street, you’d see a lanky boy in red baggy

sweatpants. His thick black eyelashes frame enormous, cornflower blue eyes and he has freckles that march across the top of

his tiny turned-up nose. When he lets loose with a belly laugh, his dimples deepen and he throws his head back while twisting

the front of his shirt. He prefers wearing stripes—T-shirts, and turtlenecks mostly. He’s very particular about

this. There have to be stripes.”

As

a mother, I was already smiling. My son is a big man now, with great heart and great shoulders, carrying his own world upon

them, but how well I remember that sweet little face then, those moments of shining brightness, the up-turned nose and freckles,

the childish chortle that would remind me, in my adult world, how to laugh.

So

Monica Holloway quickly became my friend. My distant alter ego, struggling with parenting and its myriad challenges.

The particulars didn’t matter. What mattered to me as a reader was that I recognized a mother who loves her child with

every fiber of her being, and would do anything but anything for him, even the toughest task of all—step back and let

him occasionally take a fall on his own. I won’t say that all her parenting skills were perfect. Who am I to know? There

is no manual, only heart required, lots of it and always open. Holloway has that. And in her self-effacing style of telling

the story of Wills and his golden retriever pup, Cowboy, she was touchingly willing to put her own shortcomings out there

for public scrutiny. Her writing style reminded me a little of the popular author Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat, Pray, Love and Committed), juxtaposing serious medical concerns

(in Gilbert’s case, the seriousness of the pain of a marital breakup) with delicious moments of humor. After all, sometimes

life hurts so much all you can do is laugh and get on with it.

Using

animals as therapy may not have initially been Holloway’s intent, but as most mothers do, she operates by instinct.

When Wills has a particularly bad day—sobbing when his classroom of peers are too loud, too fast, too bustling with

a confusion of activity, for instance—Holloway makes a detour to the pet store. She brings home guinea pigs, hamsters,

fish, rabbits, hermit crabs, turtles, in short, a menagerie of critters to soothe and amuse her son. And it works. Any pet

owner will tell you, and the medical profession, too, that our pets can relax rattled nerves, lower blood pressure, and alleviate

a sense of isolation. It is not unusual to hear about animals opening up humans to functionality when other humans fail to

do so. Buying the boy a puppy seems a natural progression on the animal chain of pets.

While

I may question Holloway’s decision to be very close-mouthed with others about her son’s autistic spectrum disorder,

and by doing so isolating herself and her family from social support and no doubt other avenues of help and advice, I will

not judge her for it. I have not raised her son; she has not raised mine. Every individual is different, and if I have learned

to trust anything, it is a mother’s loving instinct on raising her child. I trust that instinct even over medical professionals.

I have had reason to do so. Perhaps she does, too. Wills, after all, is highly functioning, and really quite bright. The words

that come out of this babe’s mouth gave me quite a few occasions for my own belly laugh in reading about his young life.

There is no quibble with the boy’s high level of intelligence and wit!

So

there is Cowboy, the other great personality in this story, the furry charmer. Cowboy is actually a girl dog, and she arrives

with a medical issue of her own—canine lupus. Another thing I did not know: dogs, too, can get lupus. When Holloway

first brought the puppy home from a pet store, even as she knew that buying dogs from pet stores isn’t always a good

idea (puppy mill sources), she did not know about the lupus, only that the pup seemed infected with something. Cowboy did

live about two and a half years, and charmed years they were. The Holloway family falls in love with her and she with them,

but no one more so than Wills. The photographs alone in the book are enough to make one’s heart toasty warm: the boy

and the dog curled up together in deep sleep, romping in play, snuggling. Where humans have fallen short in easing the boy’s

discomfort in adjusting to the world around him, the dog nudges him beyond his comfort zone and inspires him to go beyond

his earlier limits.

The

Holloways spend a great deal of time and money on their son, and it is a blessing that they apparently are able to do so—maxing

out credit cards, dipping into and emptying accounts, while taking Wills to a laundry list of specialists and therapists,

even hiring someone to “shadow” him in school while he adjusts, a school they actually hired a headhunter to locate

after Wills was rejected at a dozen others because of his disability. Not all parents have such means, but lucky are those

who have them to use. We all do whatever we can for our children, and then some. Nothing can carry us through like the unconditional

love of a good mother.

Love

carries us through even when we have to deal with a very painful loss: Cowboy eventually succumbs to his lupus. Still a young

dog, she dies, and having gone through that, too—the loss of a much loved pet that stayed true when not all humans would

or do—I understand the grief the entire Holloway family feels. Yet the wonders Cowboy was able to accomplish for Wills

live on. He is much more social, much more comfortable in his daily routine, because of those two plus years with Cowboy as

constant companion.

This

is a tender love story—between mother and son, between boy and dog. It tugs at the heart in all the right ways and by

all the right strings, with laughter and tears, surprise and delight, frustration and grief. Whatever the particulars of how

any one family chooses to deal with their problems, one thing rings true. Everyone needs a safe place in life in order to

thrive. A place where we know ourselves loved for who we are, and are always encouraged to be more.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sleeping with Cats: A Memoir by Marge Piercy

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

·

Paperback: 368 pages

·

Publisher: Harper Perennial,

2002

·

Price: $14.95

·

ISBN-10: 0060936045

·

ISBN-13: 978-0060936044

An

honest writer will admit that everything that he or she writes, down to a grocery list, is in some form autobiography, revealing

the author's sense of life, core values, interests. The art of literary expression, like any art, is a self-portrait, and

the higher the level of quality, the truer we have been to ourselves. When a book reads flat or false, suspect a lie.

When

Marge Piercy writes—and she writes like nobody’s business, having to date published 17 novels and 17 collections

of poetry—she comes to life on the page. Piercy is the perfect illustration of a writer’s words shaping the self-portrait,

because it makes no difference what genre or style she chooses, she rings true. Poetry or prose, fiction, nonfiction, science

fiction, no doubt even that grocery list, show facets of the author. Reading this memoir, Sleeping

with Cats, confirms that accuracy, adding layers of understanding to her creative work, for here we see her characters

at their birthing place, in the lifelines of Piercy herself.

Piercy

was born in the mid 1930s in Detroit, Michigan. Her ethnic background is Jewish and Lithuanian, but it is the former that

roots most deeply in her. Her father was a hard-hearted man, an often abusive husband and father, never letting

her forget he would have much preferred a son. Their relationship moved between cool and cold, their most successful conversations

“about the Tigers and the weather.” In his entire lifetime, Piercy's father never read any of his daughter's

books.

Her

mother was a submissive woman who made a career of repressing dreams while trying, as emotionally battered women do, to please

the husband that would not be pleased. Yet she knew her feminine powers and used them like weapons or tools of survival, while

they were not enough to save her own dwindling spirit (and perhaps contributed to its brokenness). She seemed to resent the

unbreakable spirit in her daughter, who observed as a girl her mother around other men:

“Half the men we dealt with were convinced she was crazy about them, but she mostly felt

contempt. They were marks. She had a job to do and she did it. She was obsessed with my father, not with any of these men

about whom she had a rich vocabulary of Yiddish insults which she muttered to me after each encounter.”

It

was a tough childhood of gangs and early sex, with boys as well as other girls, of a pregnancy at age 17 that Piercy had to

abort herself, nearly bleeding to death in the process. She never would have children, never wanted them. She learned about

life through the hardest knocks, losing a young girlfriend turned prostitute to a heroin overdose (“I understood why she had let her pimp get her hooked: it numbed her.”), and having her fingers broken

by her angry father, and always knowing herself different, an outsider—yet somehow never really doubting her own worth.

She made being different work for her. These were the makings of a young woman who would become one of America’s strongest

feminist voices.

Piercy

is educated at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She wins scholarships. She earns top grades. She is self-sufficient

in all things. Piercy is smart and she knows it, and she uses her mind with equal prowess to using her sexuality, enjoying

both, lavishing easily in the pleasures each provide. Swearing to never marry (“Marriage…

seemed to me a kind of death for a woman, in which she lost not only her will and her power but even her name. I was determined

never to marry…”), she marries early, and marries three times. Piercy makes no saint of herself here, nor

does she demonize her husbands or lovers. They come to one another with faults, give love best they know how, leave with a

few scars left behind but also gifts and valuable lessons.

Piercy’s

second marriage is open, like it or not, at her husband’s insistence. She comes to accept her husband’s affairs,

focusing on her own interests and literary pursuits. Eventually, she takes a lover of her own. It is the 60s, a time of hippies

and communal living and making love not war, and Piercy embraces this period of exploration. It works for her. Never becoming

a mother, she becomes instead something of a communal mother, the woman at the center of the group, cooking and caring and

cleaning for all, maintaining a kind of sanity and order to things. There is something about Piercy that is both rule breaker

and order maker, the center of the storm and the anchor in chaos. Her husband’s affairs work only when the other women

show her due respect and, preferably, friendship—often a closer one with Piercy than with her husband, the shared lover.

Writing

and cats are the thread that binds a life that moves from Detroit to Chicago to New York to San Francisco to Paris to Cape

Cod, with a few detours between. Piercy is determined to succeed at her art, and she maintains a disciplined pace at creating

novels and other works even when nothing sells, or when it does and gets no notice. Piercy has a steely will and the persistence

to carry it through. Her marriages succeed, it seems, when they give her the solid ground on which to set up her writing desk.

Her second husband gives her five years to succeed, and she sets to work with determination. If it takes her longer than that,

no matter, she shrugs off rejection and keeps writing.

Piercy

meets her third husband while married to her second, and while one relationship unravels, the third takes on strength. Ira

Wood is also a writer, and the two in some ways seem very different, including their 14 year difference (he is the younger),

but are soul mates in the ways that matter. Of her relationship choices, Piercy writes: “I

do not love primarily with my eyes. I have had lovers who were gorgeous and lovers who were plain, who were skinny and neurasthenic,

who were bulky and overweight. I have cared far more for how each of them treated me than for my eyes’ pleasure.”

Piercy speaks for most women in this, with women choosing partners who bring substance to a relationship as of primary importance,

and she finds this in her third marriage, a partner with whom she can talk and talk and talk endlessly, argue and debate and

discuss, and enjoy a companionship rich in all aspects of intimacy.

Memory

is faulty and relative, Piercy writes in her memoir, but hers always rings sound with a story that does not show its heroine

in always the kindest light. What gives her voice such strength, after all, is that she is honest in her portrayal of self,

and so, of all her characters, admitting to faults and mistakes, not shying away from moments of truth. We see the outsider,

we see the survivor, we see the woman who will never be ashamed or apologetic of her appetite for life.

At

the conclusion of each chapter is one of Piercy’s poems, adding another layer of insight to her experience. Many times,

these poetic interludes are our chance to look the deepest into Piercy’s psyche and heart. And if we ever doubt that

this woman of determination and smarts and steely survival skills lacks a more conventional feminine softness, we can be assured

it is there. We see it for those allowed into her closest circle—her cats. She loves fully her felines, her heart breaks

at their loss, and she nurtures and nourishes and pampers like a true earth mother. Her observations of their personality

quirks and antics and changing moods are often the most delightful sections of her writing. She loves and is loved unconditionally

by her cats, and as living things do, here is where she comes most alive.

Concluding

her memoir, for those who have already read some of Piercy’s works, and understanding her background gives a reader

much greater understanding of the characters in her many, many books. We see the faces of Piercy, of her husbands and lovers,

her parents, her friends, and yes, her cats. They appear in all her books, and so we see, this memoir is only one of her many

memoirs, each one a stunningly honest and open look at what makes a woman a woman, how she expresses herself in freedom, how

she loves and lets go and lives to love again—her men, her cats, her work, her homes, her world.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

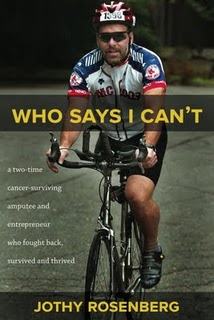

Who Says I Can’t: A Two-Time Cancer-Surviving Amputee and Entrepreneur

Who Fought Back, Survived and Thrived by Jothy Rosenberg

Book Review by Zinta Aistars

Paperback: 239 pages

Publisher: Bascom Hill Books (February 1, 2010)

Price: $14.95

ISBN-10: 193545613X

ISBN-13: 978-1935456131

If you tell

Jothy Rosenberg there is something you think he can’t do, chances are better than good that is just the thing he

will do. Chances are even greater he will leave you in the dust while doing it, too. He’s like that. He’s

probably always been like that, but what has really strengthened Jothy’s perseverance to take on life at full throttle,

meet and beat every challenge he encounters, has been his experience of being a two-time cancer survivor.

Who Says I Can’t is Jothy’s memoir, published

in 2010 by Bascom Hill Books. It is the story of “a two-time cancer surviving amputee and entrepreneur who fought back,

survived and thrived.” Jothy is an above-the-knee amputee with two-fifths of his lung removed, both due to cancer while

still in his teens. He considers “considering” a dirty word (as in, “You’re good, considering you

are missing a leg!”). Jothy does what he does perhaps in some aspects because of his physical challenges, but he achieves

excellence that can be measured against any able-bodied person. A math major at Kalamazoo College, he went on to earn a PhD in computer science at Duke University, authored two technical books, founded six high tech companies.

He has also participated in the Pan-Massachusetts Challenge bike-a-thon (supporting Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) seven times;

has completed the swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco as part of a fundraiser to support Boston Healthcare for the Homeless

16 times; and has participated in countless other fundraising sports activities. He now lives in Newton, Massachusetts, with

his wife Carole, and is the father of three children, grandfather of one. Writing a book to inspire others with his story

is just one more item added to his long list of achievements.

“The

book is about hearing the words, ‘You have zero chance of survival,’ at the age of 19,” Jothy says. “After

already having lost one leg and one lung to cancer, as well as an extensive course of chemotherapy, it is about what all of

that does to you. More importantly, the book is about how one goes about fighting back, recovering and thriving in the face

of all that adversity.”

Jothy lost

his right leg to osteogenic sarcoma at age 16; his cancerous left lung was removed while he was a student at Kalamazoo College.

Born in California, Jothy grew up in the Detroit area, the son of two physicians. His brother, Michael, was a Kalamazoo College

graduate (1975), so he knew the college well.

“I wanted

a school that was smaller than my high school and far enough away that I would not feel pressured to come home too often,

yet I still wanted to be within a reasonable driving distance. I applied for early decision to Kalamazoo; I was not the slightest

bit interested in any other school.” (Page 39, Who Says I Can’t.)

At the time

of Jothy’s dark diagnosis, chemotherapy was a new and experimental treatment. For the 10 months that Jothy underwent

the tortuous process of chemotherapy ( he still feels nauseous when he remembers it), his professors at Kalamazoo College

worked with him to keep him up to date with his college assignments. Professor Thomas Jefferson Smith was especially influential

in young Jothy’s life, and after jumping from one major to another, he settled on math in great part due to Professor

Smith’s caring attention.

“You

have to keep in mind that this was before we had the convenience of computers and e-mail,” Jothy says. “My professors

brought my course work to my hospital bedside, often written out by hand.”

Jothy writes

about his years at Kalamazoo College in his memoir—and all that came after. He says he was inspired to do so, in fact,

because of an earlier article that appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of LuxEsto. It got him thinking that he had a

story to tell and that there might be others who might benefit from reading it.

“As a

16-year-old lying in a hospital bed with one leg gone, with a mind on fire with anguish about how I might live a normal life,

and then as a 19-year-old with one lung trying to recover from chemotherapy and deal with a death sentence, I felt on my own.

I was looking for inspiration, guidance, motivation—anything. I wrote this book because I want to help anyone facing

a disability or serious life trauma deal with it better and faster than I did. Considering it took me 30 years to figure it

out well enough to be able to write it down, I hope my experiences can shorten the learning curve for someone in a similar

situation. “(Page 229)

Writing meant

reliving. Jothy grasped how much it would have meant to him to hear the story of someone who had dealt with a similar blow

and done well. A large part of what he had struggled with in those years, after all, was the feeling of being alone. Who to

ask questions about learning to walk again? How to date when you might trip and fall on your face in front of a pretty girl?

Without a role model or experienced advice, he did his best, and often, his best meant overachieving. If a two-legged person

could do something, Jothy was going to outdo it. Even when it came to dating.

“I went

on 40 dates in ten weeks when I was at Kalamazoo College,” he laughs. “Each one with a different girl.”

Not exactly

the best way to develop a satisfying relationship. That’s the kind of advice Jothy could have used. Summing up his advice

from the book, he says: “You are tougher and more resilient than you could ever have imagined. Fight back just one little

victory after another. Set a modest goal for something you can do to regain your balance and sense of normalcy. Achieve that

and set the next goal. Before you know it, you are strong and inspiring others.”

Jothy’s

“small” victories outsize those that most of us will ever achieve. Completing the circle of receiving healing

and now giving back to others, he regularly participates in AIDS fundraising bike rides from Boston to New York—a ride

of a mere 375 miles. His bike is specially fitted to him, so that he can ride with one leg. Jothy has become something

of a celebrity participant, and his memoir recounts his grueling training, frustrations, and eventual victories.

“I have

two main causes at this point,” he says. “I direct a lot of my fundraising efforts for Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

in Boston. They were on the forefront of chemotherapy work in the mid-70s, and I am convinced it played a major role in my

survival. I give them proceeds from the sale of this book and from the 192-mile Pan-Mass Challenge bike ride in which I participate

every summer.”

Yet when Jothy

is asked about his proudest achievement, it is not the physical challenges he has met, not the bike riding, long-distance

swimming, or being an expert skier. It is not even the many business startups with which he has been involved over the years.

“Without question, it is the fact that my kids like me and are proud of me. Like any father, I am insanely proud of

them, too. We are truly good friends, and that is not something I take for granted.”

If the memoir

is meant to give comfort and advice to those undergoing adversity or physical challenges, Jothy also hopes it gives those

of us with limbs intact a better perspective on how to treat those who are different from ourselves. What he wants people

to understand: “Don’t stare, and teach your kids not to stare,” he says. “But don’t ignore such

people either. Feel free to ask a question. Just remember, we get lots of attention for being different, and that can be tiresome.“

Jothy wouldn’t

call his early brush with death a blessing, challenging him to become a better man—although he believes it has in fact

done that. “But I never sit around wishing it hadn’t happened. I can’t wish it away. It happened. So I make

the very best of what I do have.”

“Everything

becomes difficult with a bad leg. I can’t carry things. I can’t walk any distance for lunch with colleagues or

to catch a cab. I walk very slowly and laboriously through airports. I worry about just walking down the hall to my boss’s

office. It eats away at job effectiveness. It can affect how well I do my job, how likely a job promotion is, and therefore

how much money I make. It affects my self-confidence in social relationships … Dealing with the superficiality of the

disability is important for self-confidence. Dealing with the anatomic, physical, structural, mechanical aspects of the disability

is just as important for success. With these daily challenges to self-confidence and self-esteem, the disabled person needs

a constant outlet where they can excel, where they can overcompensate, where they can leave the temporarily able-bodied people

in the dust.” (Page 228)

Along with

insights into dealing with physical challenges, the book also provides an inside look at business startups. Jothy has been

involved in starting, running or funding half a dozen startups. His memoir tells about the excitement of a new idea, the frustrations

and danger zones of obtaining venture capital, the hard work of building a dream on a good idea, and then, at times, the heartbreak

of having it swept out from under you.

Approaching

his book promotion as he does everything else in life, Jothy is promoting it with everything in him. He has a Web site, whosaysicant.org, a fan page on the social networking site, Facebook, and he “tweets” regularly on Twitter as @jothmeister. He

is currently on tour, giving talks and readings, signing books, and even trying to get a spot on Oprah’s talk show.

Someone should tell him he can’t do it. And then stand back and watch what happens.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feedback, submissions, ideas? Email thesmokingpoet@gmail.com

|

|

|

|