|

|

| Dorianne Laux |

Dorianne Laux's

fourth book of poems, Facts about the Moon, is the recipient of the Oregon Book Award and was short-listed for the

Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize. Laux is also author of Awake, What We Carry, finalist for the National Book Critics

Circle Award, and Smoke, as well as two small press editions, Superman: The Chapbook and Dark Charms,

both from Red Dragonfly Press. Co-author of The Poet's Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry,

she’s the recipient of two Best American Poetry Prizes, a Pushcart Prize, two fellowships from The National Endowment

for the Arts and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Widely anthologized, her work has appeared in the Best of APR, The Norton

Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and The Best of the Net. In 2001, she was invited by late poet laureate Stanley Kunitz to

read at the Library of Congress. She has been teaching poetry in private and public venues since 1990 and since 2004 at Pacific

University’s Low-Residency MFA Program. In the summers she teaches at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California

and Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill. Her poems have been translated into French, Spanish, Italian, Korean, Romanian,

Dutch, Afrikaans and Brazilian Portuguese and her selected works, In a Room with a Rag in my Hand, have been translated

into Arabic by Camel/Kalima Press. Recent poems appear in Cimarron Review, Cerise Press, Margie, The Seattle Review,

Tin House and The Valparaiso Review. Her fifth collection of poetry, The Book of Men, will be published by W.W. Norton

in February, 2011. She and her husband, poet Joseph Millar, moved to Raleigh in 2008 where she teaches poetry in the

MFA program at North Carolina State University.

Publications

The

Book of Men (W.W. Norton)

Facts

about the Moon (W.W. Norton)

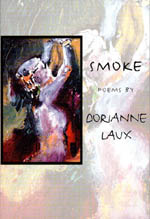

Smoke

(BOA Editions, Ltd.)

What

We Carry (BOA Editions, Ltd.)

Awake

(Carnegie-Mellon Classics)

Dark

Charms and Superman: The Chapbook (Red Dragonfly Press)

In

a Room with a Rag in My Hand, Selected Poems (Arabic, Kalima Press)

The

Poet's Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry (W.W. Norton)

Zinta for The Smoking Poet: Dorianne, welcome. To you and to The Book of Men, this slim new collection

of poetry with its striking cover of flowering and mushrooming phallic symbols arranged in slightly yellowed briefs (love

it), published by W.W. Norton, and available February 2011. It is a wonderful thing, to watch, read, experience

the evolution of a poet, although, like Zeus, you seem to have been born whole, a poet complete. What do we find in The Book of Men that we may not have found in your previous collections, or found only the hint of it?

Dorianne Laux: I’m not sure.

It all seems of a piece to me. The first section is devoted primarily

to the men alluded to in the title: men from my past, the man on the street,

famous men, men of myth, men who have influenced me, the heroes and anti-heroes of my life and imagination. Vietnam and the Iraq war collide in one poem, locales shift between the west coast and the east, poems

of youth and age. But mostly these are poems that spring, as usual, from my very

ordinary days.

TSP: Reading through the collection, one theme seems to rise to the top most, or one

image: that of the imperfect hero, or the imperfect idol. Which perhaps is the very definition of Man? The opening poem, “Staff

Sgt. Metz,” is about a girl, then woman, you, observing adored men in your life—a brother, a boyfriend, a military

hero—and noting how their/your youthful idealism dies. Yet, somehow, that’s still all right. It does not lessen

anyone, this disillusionment. One life at a time, all still wonderful. “I don’t believe in anything anymore:/god,

country, money or love./All that matters to me now/is his life, the body so perfectly made/…”

That idea of the very human (i.e., imperfect) hero shows up again and again, throughout. Superman

encountering kryptonite. Mick Jagger with his rubber mouth and “beef jerky jowls,” grotesque and wonderful at

once. The Beatles breaking up after reaching such heights because nothing is enough. In “The Secret of Backs,”

our momentary unwillingness to see our beautiful idols with their perfect napes turn around and show their imperfect human

faces. The rebellious yet adored foster child. The very human Cher turned plastic. Your mother after suffering a stroke, that

tenderness for an aging woman. Even gold, so worshipped in our materialistic society, is revealed as something for fools,

not gold at all, but present in everyday things. Imperfection. Humanity. Brokenness. Commonness. Observed, with tenderness,

and loved for exactly that—the imperfection of these people and things. Else why bother to love? No greater beauty than

our imperfections and our imperfect moments?

Dorianne: Disillusionment and imperfection. That

pretty much sums it up. Your questions are so comprehensive, much better than

my answers. Mostly I see it as a long love poem to a time, a hidden culture, that of the ordinary hero, the one who gets up

each day, knowing he or she will do almost nothing right, and gets up anyway. I’m

for the one who slogs on, who goes to work or school when they don’t feel like it, the ones who don’t give in

or give up. Those people are my heroes, which is pretty much everyone.

Your idea of imperfection led me to look it up. I found

a few interesting quotes. One from Ernst Fisher, a German chemist, who observed

that “As machines become more and more efficient and perfect, so it will become clear that imperfection is the greatness

of man.” Maybe that’s something of what’s behind my desire

to seek out imperfection at this particular moment in our rapidly advancing technological history. I also liked what Thomas Carlyle has to say, “Imperfection clings to a person, and if they wait till

they are brushed off entirely, they would spin forever on their axis, advancing nowhere.” We often think of our imperfections as holding us back, whereas here we see that it can also be the force

that pushes us forward. And I love his use of the word “clings”. Our imperfections do seem to cling to us, sheer as a curtain or a bandage. But from an artist’s point of view, I like most what Ben Okri, a Nigerian author and magic surrealist,

has to say: “The act of storytelling hints at a fundamental human unease,

hints at human imperfection. Where there is perfection, there is no story to

tell.” I think my poems seek out human imperfection because that is where

the story is, that’s the seed from which all the rest springs. There’s

a wonderful poem by Lewis Hyde who wrote a book called The Gift which is a long

essay about how poetry is outside of the world of commerce and creates tribal community by passing along emotional lore. This is an excerpt from the title poem of his poetry collection called, This Error is the Sign of Love.

“This error is the sign of love,

the crack in the ice where the otters breathe…

The fault in the sea floor where the fish linger and mate…

seeds that need six months of drought, flowers shaped for the tongue of a moth…

The hail storms in South Dakota that started the Farmers Cooperative in 1933.

The Sargasso Sea that gives false hope to sailors and they sail on to find a new world,

The picnic basket that slips overboard and leads to the invention of the lobster trap,

The one slack line in a poem where the listener relaxes and suddenly the poem is in your heart like

a fruit wasp in an apple, this error is the sign of love!

You can read the whole poem here: http://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/index.php?date=2000/12/12

TSP: Along those same lines, your poems draw the eye to our bumbling through life, how

random it all is. You skip the big things and find the seemingly little things and the in-between moments, so that we don’t

miss the importance of the detail. “Late-Night TV,” for instance, is about the man in the infomercial, whom you

lift out of the droning insomnia moment and into living room reality. We realize he is us, we are him, and everybody is somebody

and there is a miracle in there somewhere.

We know nothing of how it all works,

how we end up in one bed or another,

speak one language instead of the others,

what heat draws us to our life’s work

or keeps us from a dream until it’s nothing

but a blister we scratch in our sleep.

It’s an interesting trick, this. Bring us down to size at the same time that you help us understand

our value.

Dorianne: I like what you say, Zinta: “We realize he is us, we are him, and everybody is somebody and there is a miracle in there somewhere.” Yes. Amid the banalities we sometimes

make of this life, somewhere, a miracle. Human life is not valued enough. All life is not valued enough. My husband

and I were talking today on our walk about how those who go to war can become addicted to the way it makes people come alive,

as in the movie “Hurt Locker”. We have all become addicted to crisis,

extremity, intensity. Look at our news channels, our movies, our video games

and YouTube clips. We want to be shocked, terrified—mayhem and death everywhere. Are there other ways to make us aware of how fragile life is? We began then to talk of the purpose of art and poetry, and how when we read a poem or look at a painting

we are led into the true intensity of life, the one right here as we walk down the street and are struck again, as if for

the first time, by the changing of the leaves from green to gold, that brief glimpse into the final hallway. Maybe the purpose

of art is to help us apprehend the loud silences, the shimmering depths, the small intensities of ants going about their business,

tunneling out whole cities beneath our sidewalks, and awake us to the absolute mystery that is life. Art asks us to contemplate death rather than to simply imagine it or even press ourselves up against it

as we do in our youth. It’s coming, no matter how fast we run from it or

toward it, and art asks us to stop and confront death rather than being merely tolerant of, tempted or titillated by it.

TSP: You have one of those random moments yourself in “Juneau Spring,”—“I don’t know now/why I ever left”—juxtaposing one life against the life

of the ages in an immense glacier outside your window, falling away. Too big things silence us. You lived in Juneau at some

point in your life? Alaska is one of those places that is about grand, about big, about life in heroic proportions, yet ice

chips and falls away there, too. Against the background of a glacier, we see Dorianne as waitress, serving mugs of beer…

Dorianne: I did live for a time in Juneau, in my early twenties, and waitressed at the famous

Red Dog Saloon. I am interested in setting humans against a large backdrop in my poems because that’s the truth of our lives;

we’re tiny moving dots on a huge planet, that planet itself a moving dot in the immensity of the universe. And yes, Alaska is a place that allowed me to see my insignificance very early on, clearly and eerily,

in a landscape that does provoke silence, which is a poet’s best friend. That’s

the struggle, really, to believe that life matters, that we matter as individuals, even as we also know how small and inconsequential

we really are. The poet’s job is to try to say something in the face of

that immensity and silence.

TSP: In this collection, you allow men their weaknesses and frailty, but in “Second

Chances” you also let us see how cold and appetite-driven man can be, too. It is a poem that gives us a sense of how

slim are the odds, how very small the chances that a man won’t take advantage of a woman when she is defenseless …

or do you think that slim chance will happen and he will protect her instead? Is there such a thing as second chances?

Dorianne: Again, that’s the mystery. It’s

not news that we are capable of evil; that we are capable of good is what amazes me. There are those who would see that young,

vulnerable woman and take her in, show her kindness. Yes, the chances are slim,

but that there is a chance at all is a kind of human miracle. And yes, I believe

in second chances. We are given, every day, the opportunity to make a change

in our lives, in someone else’s life, and sometimes we do. And I think

you could also see weakness in a man who is “cold and appetite-driven”.

I guess I’m calling on that man to find his strength, to step up and employ this oddly inherent humanity.

TSP: Women have their limelight moments in this collection, too. “The Rising”

is incredible. The strength of the mother. In this case, that mother is a pregnant mare. The entire poem is about this mare

rising up from the field with her “beastly burden,” and we feel every bit of that tremendous effort and every

pull of the planet’s gravity that tries to hold her down. It’s a remarkable poem.

“Middle Name” shows us two women, your mother and her best friend, your namesake, and you as the third,

an infant in their arms. There is “Cher,” and “Mother’s Day,” with women doing battle with age.

If there is one thing absent from this collection it is gender wars. You point out differences,

perhaps, but we all have our own demons and battles to wage. We all want to live our lives best we can. We all make mistakes.

We all love and want to be loved.

Dorianne: Thank you. And

yes, there is that force pushing us down, daring us to get up. But gravity also keeps us grounded, keeps us from floating

away into the nothingness of space. Again, it’s this tenacity that astounds

me, the pushing up and on, the desire that comes from where? to do well, to do good, to accomplish something with our lives

before they run out. As I age, I find myself looking at people with more wonder. It’s interesting, because I think of “The Rising” as a metaphor

for the human will to care for the burden of life inside us, and so I wonder why I didn’t go ahead and do that, write

the poem with a real pregnant woman getting up from a couch or hanging on to a subway strap, bags hanging from her shoulders,

her free hand embracing her lower stomach, those thick bands of aching muscle. Maybe

I will write that poem. But it was the horse that made me see the human. And I think it helped me to concentrate on the sheer physicality of pregnancy, the

amazing endurance and Olympic event of it, which we often overlook when we see a pregnant woman.

TSP: Unmistakably, this is a collection by a woman poet who has come far enough to understand

a few important things. Far enough to have perspective when you look back. Far enough to ask, “Who Needs Us?”

This poem is raw honesty, vulnerability, and so very human in its wonderings about why we are here at all.

Who needs the footprints of us,

the glimpse of us in a corridor of stars,

who sees the globes of our breath

before us in winter; the angels

we make in the stiff snow,

the hack and ice of us, the glide

and gleam and busted puzzle of us,

the myth and math of us,

the blue bruise and excuse of us…

So, do we matter? Only to ourselves? On your own path, have you found life-meaning and satisfaction

in being a poet?

Dorianne: Well, my earlier answer applies here—even if we only believe we matter in spite

of the obvious fact that we don’t, that’s enough. It’s my struggle

to decide fully that gives rise to the poem. I live somewhere between the yes

and the no. I have found satisfaction in being a poet, and in being a mother,

a teacher, a wife, a friend. I rarely feel like a poet. Often I feel lost and alone and confused. And then there are

these moments of grace.

TSP: While there is a bitter sweetness in so many of these poems, a tender touching of

painful places, one stands out as a moment of stubborn and delicious rebellion: “Antilamentation.” Regret nothing,

you say. Tell us about the moment surrounding this spitfire poem, in which it was born.

Dorianne:

You know, that poem was written

a long time ago. It was first published in the Spring/Summer Issue of The Alaska Quarterly Review in 2000, which means I probably wrote it a year or two before that, and so I’m

not sure I can reconstruct how it came about. I do know that I love Billie Holiday

and especially her renditions of No Regrets and Don’t Explain. And my husband, Joseph Millar, is always telling

his students, “Don’t Explain, just write.” That could all have

gone into the hopper to make the poem. If my math is right, and it often isn’t,

I was around 45 when I wrote it, so I may have been feeling that middle-aged angst we all come to know so well. I liked the

idea of taking someone’s hand, someone who was having the same doubts, having a James Wright moment, wondering if she

had wasted her life, and telling her not to worry so much, to become a key in the lock of the present and live there for a

while. I love the lyrics from both those songs. I can’t say for sure, but

I would bet they were kindling for the poem.

Hush now, don’t explain

You’re my love and pain

My life’s your love

Don’t explain

and

I know our love will linger

when the other love forgets

so I say goodbye with no regrets

TSP: Once again, the moon has struck (Facts About

the Moon is your previous collection.). “Dog Moon” is one of our favorite poems in this collection. What is

this love affair between you and the moon that it can bring you to such fine howl?

Dorianne: The moon is such a cliché, and I have to say I enjoy reinventing clichés in general. The moon? What can one say about the

moon that hasn’t been said, and yet there it is, asking to be spoken to. When

I heard that old dog start up I just couldn’t resist. For him, the moon

is far from a cliché, it never gets old. He gave me permission.

TSP: The book is dedicated to poet Phil Levine. What has he meant to you in your evolution

as a poet?

Dorianne: Everything. He

noticed my work and gave it credence. He continued to support me book after book. He’s a terrific role model—he works at his art daily, no excuses, and

shows no signs of slowing down. He has high standards. He’s completely

honest, in his poems and in his life. And he’s a mensch, a no bullshit real person in the world, a good and honorable

man. I look to his poetry and his life as a guide.

TSP: What other poets have been of influence, for no man or woman is a poetic island

… ?

Dorianne: So many. Right now I’m fully into Mark Doty and

have been imitating him in order to find a new line length, a new way of seeing and being in the world. I also want to start

playing with syntax more in my poems, so I’ve been re-reading C.K. Williams and Gerald Stern, long time favorites. I was just at the Dodge Festival with Sharon Olds so I was able to hear her read new

poems. She was an early influence and I love seeing how she just keeps getting

better and better, and how her humor is reaching new levels, how she considers a topic, stringing it out to the ends of the

universe! I’ve also been traveling with Marie Howe, another early influence,

and I am so struck by her power, how she can say a simple thing, or take a snippet of conversation, and find the raw edges

of it, then bring us back so viscerally, to the real and the now. I could go

on, but these are a recent few that spring to mind.

TSP: Tell us about teaching, Dorianne. You are not only poet, but teacher, a professor

who has taught in many places across this country and others, traveling to connect with poets and students of poetry. Can anyone write poetry? Or do you teach a craft, and beyond that, release a flock

of new birds to either take wing or crash in their search for the art beyond the craft? What guidelines do you give, what

great wisdom that has been imparted to you, or gleaned by you, that you now pass on? And, no doubt, every good teacher also

learns from her students …

Dorianne: Most of my classes are generative. I bring in some

poems, read them with an eye toward an issue of craft, and then invite students to imitate in a 20-minute exercise. Lately

I’ve been talking about structure, how free verse is dependent on patterns, and working to discern those patterns and

make use of them which can help to free up the poet and the poem. I’ve begun to make “maps” of free verse

poems, asking what the poet is doing line by line, stanza by stanza, how the whole is comprised of parts, each doing their

small job, like clockworks, in order for the whole thing to move, to work. It makes us aware of how much goes into the building

of a great poem. And yes, I think you can learn from that kind of close reading.

Of course, those are mechanical issues, and if we stay with the clock metaphor, you can only hope that those mechanisms will

open up into the mysteries of time and timelessness, that passionate tempo that rushes all things forward. Though that’s

in hands of the student poet. My job is to lead them to poetry, but they are the ones who must dip their long beautiful necks

and drink.

TSP: Why poetry and not prose? Although you do, on occasion, write prose. Is a writer

predominately meant for one more than the other?

Dorianne: I admire fiction writers, and read a lot of fiction and non-fiction. I just finished Ishiguro’s Never Let me Go and am in the

middle of Rock and Roll Can Save Your Life by Steve Almond. So loving it. And though I’d like to be able to write

prose or fiction, I just can’t seem to go over a page and a half. And characters

won’t speak to me. For me plot is a just hole in the ground.

TSP: Where can readers find out more about you, talk with you, keep track of you, rub

elbows with you, and perhaps even play a game of Scrabble with you?

Dorianne: Oh Facebook, of course. I’m addicted. And YouTube. And I have a new Website made for me by my friend Enzo Surin. You can check it out here: http://www.doriannelauxpoet.com

TSP: Ever light up a cigar?

Dorianne: I just read a wonderful memoir by a former student,

Peter Hoffimeister, called The End of Boys, which will be out soon on Soft Skull

Press. There’s a scene in which a man who’s picked him up hitchhiking offers him his first cigar. His description

of smoking it is wonderful. It reminded me of the times my former students Matthew

and Michael Dickman, Mike McGriff and Carl Adamshick, all used to smoke cigars on our back porch and talk about poems. I’d

go out sometimes and take a puff or two. Luscious! And the smell?? Divine.

TSP: Thank you, Dorianne. You inspire.

To read a few poems from The Book of Men, see Poetry of Dorianne Laux.

|