|

Something Knows the Moment by Scott Owens

Book Review by Kim Grabowski

ˇ Paperback: 120 pages

ˇ Publisher: Main Street Rag (July 2011)

ˇ Price: $15.50

ˇ ISBN-10: 1599483025

ˇ ISBN-13: 978-1599483023

Scott Owens’ Something Knows the Moment, is an interesting,

in-your-face exploration of God, faith, and immortality. I am not a particularly

religious person (I always say spiritual, not religious), but there is something so irresistible about Bible stories—and

the retelling of Bible stories, in particular—that never fails to pique my interest.

Owens’ book is broken up into five sections: Acts of Creation, The Lives of the Saints and Others, The Angel’s

Night Off, The Persistence of Faith, and What to Make of a Ruined Thing. Each

section blends old images with new in order to re-appropriate religious motifs, updating some and preserving others.

“Acts of Creation” follows the foundational stories of the Old Testament: God creating the

universe, and Adam and Eve. Though this first section of poems does have a more

Biblical feel to it, Owens is already aiming to tweak the stories. God, in these

poems, is messy, he “pisse[s] stars across the sky,” and works best on a Tuesday and worst on a Saturday, when he’s “waiting for the night’s carousing,/ the next

day’s sleeping in.” The foundation of Owens’ book is a God who is achingly humanized—lonely, ambivalent

toward his creations, and disorganized.

In “The Lives of the Saints and Others,” and “Angel’s Night Off,” Owens extends

his reach to other figures, focusing more on Adam and Eve, angels, and other characters.

In “For Those Grown Tired of Angels,” Owens urges: “Better to stay this side of human,/ uncertain,

unclear, imperfect,/ and constantly working/ towards what you think might last.”

In the final two sections, Owens takes a step away from the old stories and takes a hard look at faith

and doubt in today’s world. In “The Absence of Anything as Certain

as a Burning Bush,” the poems speaker claims “You’re certain the signs are everywhere,/ but you don’t

know what they are/ or worse what they mean.” One poem explores the way

in which our present-day society clings to some Bible quotes and discards or ignores others.

In a world like ours, how do we go on believing? What does faith give

us and what does it take away? Is it possible that “the way to heaven/

[is] as simple as persistence?” Ultimately, the poems seem to do more doubting

than they do believing. God, today, is banished “On the Island of Misfit

Toys.” But there are still moments that break through the speaker’s

experiences and suggest there is something more than this world—his wife taking care of a feverish daughter, “All

the atrocities of man assuaged by this hand, this hair.”

Overall, Owens’ goal is an interesting one. I am always

up for pondering the ways in which religion has affected our modern lives—how we cling to stories, and how those stories

could have been different.

Scott Owens is the author of seven collections of poetry and over eight-hundred poems published in journals

and anthologies. Owens is editor of Wild

Goose Poetry Review, Vice President of the Poetry Council of North Carolina, and recipient of awards from the Pushcart

Prize Anthology, the Academy of American Poets, the NC Writer’s Network, the NC Poetry Society, and the Poetry Society

of SC. He holds an MFA from UNC Greensboro and currently teaches at Catawba Valley

Community College. He grew up on farms and in mill villages around Greenwood,

SC.

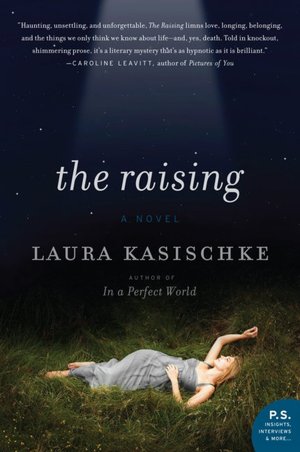

The Raising by Laura Kasischke

Book Review by Kim Grabowski

ˇ

Paperback: 496 pages

ˇ

Publisher: Harper Perennial, 2011

ˇ

Price: $14.99

ˇ

ISBN-10: 0062004786

Before I picked

up Laura Kasischke’s new novel, The Raising, I hadn’t read a non-school-related novel from start to finish

in a long, long time. We’re talking years, here. Usually, I spend my precious armchair-time (or subway time,

or kitchen table time, or restaurant time … let’s face it, I bring a book along with me everywhere I go) glued

to a book of poetry. It is not uncommon for that book of poetry to bear Laura Kasischke’s name on the cover. She has

authored eight collections of poetry. Over my extensive winter break from Kalamazoo College, I made it my mission to

read all of them, and Kasischke’s place as one of my favorite authors became more and more secure as I read. It’s

possible that nothing else, short of a novel by Kasischke, would give me such incentive to crack open a 461-page work of fiction

and run with it.

Then again,

maybe I should revise my first statement. It would be wrong to call Kasischke’s new novel “non-school-related,”

as one of my major points of praise is the accuracy with which Kasischke represents college life. The story is set at Godwin

Honors College, a small residential college that is part of a larger, fictional university in Michigan (though the setting

does share many qualities with the University of Michigan, where Kasischke teaches, the story is not limited to the realistic

institution). The novel centers around the tragic death of a seemingly perfect, angelic sorority girl, Nicole Werner, the

result of a car accident. “And all the winds go sighing,/ for sweet things dying,” reads the epigraph,

a quote from Christina Rossetti. The campus is devastated. Nicole’s sorority sisters at Omega Theta Tau want revenge.

But what if

Nicole isn’t really dead? Or, what if she’s back from the dead? Not only have students reported seeing

her on campus, they’ve reported sleeping with her. Kasischke’s novel explodes down this plot path. At first

I groaned a little bit inside, weary of my generation’s obsession with the undead. In retrospect, this is the exact

reaction Kasischke intended. What begins as your run-of-the-mill vampire/zombie story begins to break down and blur the lines

between reality and fantasy. Is Nicole really back from the dead, or is this all just superstition running amok in the campus

community? If it really is superstition, why do I, as a reader, start to wholeheartedly believe in Nicole’s return?

We want to

believe that we can cheat death, especially when we’re young. Maybe I am, as a college student, especially primed to

believe the legend being woven at Godwin Honors College. The book’s exploration runs deeper than fantasy versus reality,

though. Kasischke is also prompting us to reexamine what individuates us, as opposed to what makes us like everyone else.

When one character condemns the conformity inherent in sorority life, Josie, one of Nicole’s former sorority sisters,

counters: “ ‘Like that’s not how it is with everybody?...Like all the counter-culture kids, or all the conservatives,

or all the professors or librarians or bookstore clerks around here aren’t, every one of them, completely interchangeable?’”

There is something

comforting, almost instinctual, about our need to belong. But, as a result of that need, do we, ultimately, lose ourselves?

Are we condemned to erase our own senses of individuality, pay a steep price to be a part of some semblance of a whole?

Ultimately,

I think Kasischke would champion individuality. This book prompts us to take a long, hard look at ourselves. I noticed, when

I was thinking in terms of “anyone” versus “one,” that, although the book is told from a multiplicity

of perspectives, a sorority girl never takes narrative center stage. They don’t want us inside their head (and

I say “head,” singular, because the sorority in Kasischke’s novel is one undifferentiated body). There’s

a community there that is just as grounded in the people who are kept out as those who are let in. You can defend the Greek

system all day and all night if you want to, but you would be missing Kasischke’s point. “Types. Ideals. Representations.

Nearly exact copies of one another.” How do we escape it? Or, more importantly, do we want to?

I became so

attached to this book. By the end, I felt as though I truly knew the characters. They were far from interchangeable. As I

suspected, Laura Kasischke’s fiction did not disappoint. “The scene of the accident was bloodless, and beautiful,”

the book begins. From that moment on, we are catapulted into a world of suspense, a world simultaneously aching for truth

and fantasy. Before I set out to read this, I joked that my attention span was no longer suited to long-form fiction. With

The Raising, Laura Kasischke has reminded me what it feels like to pick up a novel and feel as though I haven’t

taken a breath until I’ve closed the back cover on the final page.

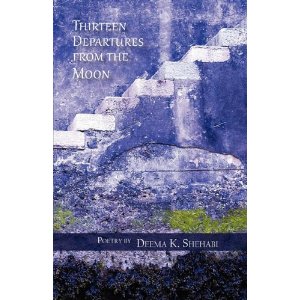

Thirteen Departures from the Moon, poetry by Deema K. Shehabi

Book Review by Kim Grabowski

ˇ

Paperback: 92 pages

ˇ

Publisher: Press 53, 2011

ˇ

Price: $12.00

ˇ

ISBN-10: 1935708236

ˇ

ISBN-13: 978-1935708230

Deema K. Shehabi’s first book of poems, Thirteen Departures

from the Moon, invites readers down a path with a speaker on a search for identity.

Shehabi’s poetry is lyrically rich, setting up an image palette of “the blue of Palestinian pottery,”

the tides, and, again and again, of roots. My first impression, upon finishing

the slim volume, was that I had just been travelling to places that felt, at once, foreign and familiar.

“Freedom is land” insists the speaker of the poem

“Blue.” But if this is true, how do members of a diaspora find freedom

and wholeness? Shehabi’s book is ambivalent toward the answer, as it is

not a question that warrants a simple explanation. Instead, her poems seem to

weave land, flesh, and heavens together, claim that “we grow large with rootlessness.” At the very moment we can’t be defined by our roots, we seem to pick them up and carry them with

us, until “ ‘There are no boundaries/ between you and the moon…’”

This, to me, was one of the most interesting aspects of Shehabi’s book. She could have left us with twenty-nine poems that explored a search for belonging, and the book still

would have been interesting and richly constructed. But, then, she does not allow

things to remain so simple. Shehabi is constructing a narrative of what it means

to belong in a diaspora today, what it means to pick up the fragments of Palestinian pottery and fashion art out of them,

as well as longing.

Beyond Shehabi’s fascinating subject matter, Thirteen Departures

from the Moon is a book assembled by a poet who is deeply concerned with craft. I was especially interested

in the way Shehabi wove together narrative and lyricism, as well as how she pieced together words from other source material. “For every one gone to earth, one hundred roots are planted,” speaks one

poem, a line taken from a Palestinian peasant saying. In the poem “Khadijah,”

the speaker wonders if she has become “fractured/ and preoccupied only/ with [her] own mending,” which is a line

adapted from Frank Gaspar’s poem “It’s the Nature of the Wing.”

In writing this book, it appears Shehabi was acutely aware of a goal to allow form to reflect subject matter, in that

the poems give off an aura of inheritance, of fragmentation, and of wholeness, all at once.

Deema K. Shehabi is a poet, writer, and editor. She grew up

in the Arab world and attended college in the US, where she received an MS in journalism.

Her poems have appeared widely in journals and anthologies such as The Kenyon

Review, Literary Imagination, New Letters, Callaloo, Massachusetts Review, Perihelion, Drunken Boat, Bat City Review, Inclined

to Speak: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Poetry, and The Poetry of

Arab Women. She currently resides in Northern California with her husband

and two sons.

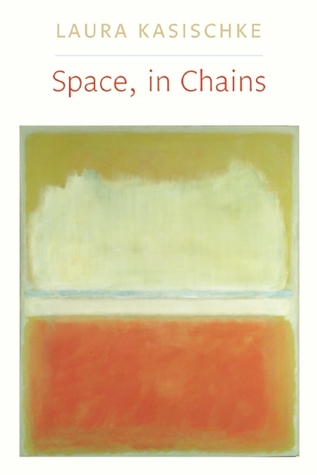

Space, In Chains, poetry by Laura Kasischke

Book Review by Kim Grabowski

ˇ

Paperback: 110 pages

ˇ

Publisher: Copper Canyon Press, 2011

ˇ

Price: $16.00

ˇ

ISBN-10: 1556593333

ˇ

ISBN-13: 978-1556593338

Laura Kasischke’s new book of poetry, Space, in Chains, is

the work of a masterful poet who has resolved to inhabit her imagination even more deeply than ever before. The poems take a hard look at the lives we are living, and ask us to free our minds for associative leaps

that connect the known with the unknown. “Animal shudder. Something’s coming” warns the speaker of the poem “Dread.” Indeed, Kasischke does not intend to lead her readers anywhere safe.

What are our stories, and where do they come from? What is health, what

is death, and how does the earth hold onto us after we’re gone?

Kasischke is known for an image palette that is sometimes described as surreal, and is most definitely

highly original. Her poems seem committed to breaking down our minds’ organizing

principles—“Hamster, tulips, love, gigantic squid. To live. I’m not endorsing it.” What we think is simple,

given, ordinary, is, Kasischke reminds us, the world at its most absurd.

Space, in Chains, also sets itself apart in its formal aspirations. Kasischke’s characteristically intuitive line breaks take on a new character, with some lines stretching

out into prose-like stanzas. It is clear that Kasischke means to guide us through

her imagination, setting up a mode of reading that allows us to follow her on her suprising journeys through image. Aspiring poets can learn much from this mode of line-breaking. Rather

than allowing line-breaks to dictate the shape of the poem, Kasischke allows the poem to choose its own line-breaks.

Kasischke is a poet interested in fragmentation, in narrative by means of charged moments, and sensory

appeal. The Boston Review raves “The future will not—should not—see

us by one poet alone. But if there is any justice in that future, Kasischke is

one of the poets it will choose.” It is clear that Kasischke follows her

own path through poetry. Her trust in imagination opens the door for us to trust

it, as well. What might appeal to future generations, as The Boston Review is

intimating, is that Kasischke is one of the poets of our time who is most strikingly demonstrating a movement toward newness. What is most compelling about Kasischke’s work, however, is that this newness

does not, in any way, seem forced or deliberate.

I have been a loyal follower of Kasischke’s poetry since I was first assigned one of her books during

my freshman year of college. Space, in

Chains is an exciting read for followers such as myself. It is as if Kasischke

threw caution to the wind and stepped onto the page committed to acting on her

impulses, and her impulses, alone. As

the blurb on the back of the book suggests, “Kasischke’s poetry insists upon asking hard questions that are courageously

left unanswered.” In that sense, it takes a courageous reader to experience

this book fully. Several poems entitled “Riddle,” as well as several

other strange meditations, will not only interrogate you, but force you to interrogate the poems and the world.

“They told us it was a dance, a party, a pageant, so we ran laughing together straight into the disaster”

laments the speaker of one of the “Riddle” poems. This is what Kasischke

intends for her readers: to send them running, laughing, straight into a world full of disaster, grief, and beauty.

Kim Grabowski Reviews

the Kalamazoo College Literary Magazine: The Cauldron

Those of you who hail from Kalamazoo may know a thing or two

about the lively artistic scene it boasts, in contrast with its somewhat small size. Our

community owes part of that wealth of imagination to Western Michigan University and Kalamazoo College, where young artists are constantly growing and re-defining creativity.

I took it upon myself, then, to clue our readers in to one

aspect of the artistic college community—Kalamazoo College’s literary magazine, The Cauldron. The volume of The

Cauldron that is set to appear in Kalamazoo College’s bookstore this spring is the result of a long history of publications—the

college archives contain issues from as far back as 1920. For many young writers at

Kalamazoo College, The Cauldron provides one of the first opportunities to be heard. Kalamazoo College’s writer-in-residence, Diane Seuss, who has gone on from her time

as a student at Kalamazoo College to publish widely and with great success, remembers her own experience with The Cauldron:

“My first publications were in The Cauldron—in

1974, I believe. The poems were probably bad. And the magazine was mimeographed, and stapled at the spine. But Conrad Hilberry,

my mentor, who taught creative writing for thirty-plus years at K, made it clear that ‘getting poems out there’

was important. I remember how good it felt to see my work in print, and it still does. It was cool to see the little pamphlet-sized

things floating around campus, and to be part of the community of writers who lived inside the magazine.”

Although Diane Seuss acts as the faculty advisor for the magazine,

she jokes: “the magazine functions much better if I’m a fly on the wall or a mouse in the corner …” The majority of the work on The Cauldron lies

in the hands of students at the college, in the form of genre editors and selection committees for poetry, fiction, non-fiction,

and art. Two editors-in-chief oversee the staff, and make final decisions based on

their vision for the magazine. This year, The

Cauldron staff was headed by chief editors Rebecca Staudenmaier and Cam Stewart, students in the creative writing program

at Kalamazoo College focusing on fiction and poetry, respectively. “It’s

really nice to see your work in print after you spend so much time in these classes, honing your craft. It’s nice to see it validated” says Staudenmaier. The Cauldron staff puts in hours of work to create this emblem of unity for the Kalamazoo College writing community.

This year’s volume of The Cauldron is brimming with energy and life. It has a sense of humor,

but it also asks hard questions of its readers. “It’s kind of weird, quirky,

sexual—but it’s also very personal” Staudenmaier asserts. Readers

of this year’s volume of The Cauldron will walk through a landscape of fear,

longing, and the search for identity and belonging. “We went in with the intention

of having a strong ending,” says Stewart. “The pieces that we had selected

were all of such great quality that it made it really fun.” The magazine represents

some of the most compelling work happening in a variety of artistic outlets on Kalamazoo College’s campus.

Prepare yourself, readers.

Prepare yourself for meditations on pornography, the darkrooms of high school, perversion, and reflection on what it

means to survive in this world. How we can even justify surviving it. The future of art is happening all around us in Kalamazoo, and picking up a copy of The Cauldron at Kalamazoo College’s bookstore is one way to catch a glimpse.

|