|

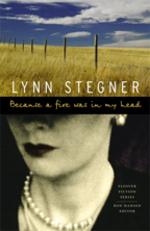

Because a Fire Was in My Head by Lynn Stegner

Book Review by Russell Rowland

·

Hardcover: 286 pages

·

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press, 2007

·

Price: $24.95

·

ISBN-10: 0803211392

·

ISBN-13: 978-0803211391

In Lynn Stegner’s fourth book, Because a Fire Was in My Head, we meet one of the most unpleasant

protagonists in the history of literature in the person of Kate Riley. Kate is the daughter of Irish immigrants in Saskatchewan,

and after losing her father at a young age, Kate learns about survival from her martyred mother, who never misses an opportunity

to let her daughter know how unpleasant her life is and has been.

From the opening scene, Stegner uses her descriptive

skills and great insight into her character as Kate watches a blind woman try and pick up the droppings her dog has left in

the gutter. Throughout the novel, Kate has a vague sense that she should feel something toward the people and the events around

her. And yet she doesn’t. In this scene, she considers telling her male companion about the woman’s plight, but

in the end, she decides ‘Who would want to share so remarkable a moment?’ It establishes Kate’s attitude

toward everything in her life. She’s not capable or interested in sharing with anyone.

But it’s fascinating

to see to what lengths our protagonist will go for her acquisitions. It turns out that this opening car ride is a trip to

the hospital, where Kate is to have brain surgery for a tumor that she already knows isn’t there. She marries twice,

both times impulsively, and both times without a hint of love, because both men offer her something she feels that she needs.

Throughout her first marriage to Jan Larsen, an hotelier, Kate arranges for afternoon trysts with other men, at one point

leaving her son in a running car for several hours. The boy almost dies from carbon monoxide poisoning, and Jan finally gives

up on her after this. This is after she’s given up her first child for adoption when the doctor tells her the baby is

blind (another falsehood), and after she has kissed a man she knows has the flu so that she can avoid breast feeding her baby.

Kate also stands by while one man paralyzes himself trying to impress her with an ill-advised (and drunken) dive.

The

thing that drives all of this behavior is what drives many of us, but which Kate never seems to find relief from, which is

an insatiable loneliness and need for love. Because she is so scarred by the loss of her father, and by the cruel indifference

of her nurse mother, who only noticed her when she was sick, Kate’s quest for these things is misshapen. She looks for

men who treat her badly, and invents her own maladies, even keeping a journal of her illnesses, both real and imagined. Stegner

makes particular good use of the time frame that the story takes place, as the options for women are so limited, and the pressure

to present yourself as successful is so focused on how you look and to whom you’re married. Kate has gotten these messages,

but she doesn’t have the self-awareness to be content with her life even when she does have it all.

And yet,

incredibly, like Kate watching the blind woman, we are transfixed by this woman and her quest for survival and fulfillment.

As is so often the case, the fact that Kate is so hard to like makes her fascinating. We want to understand. And maybe part

of us wants to even be a little bit like her. Stegner touches on that guilty desire to be unencumbered by conscience, or shame.

But this is, in the end, what makes this a redemptive story, the fact that Kate often manages to get what she wants. Because

Stegner shows so clearly what the consequences are of such selfishness. Through Kate, a woman who seemingly feels no guilt,

we learn the value of conscience. And Stegner tells the story with prose that is often breathtaking. Here’s Kate’s

own daughter’s take on her mother:

If she had been stronger, if her will had not swooned at the gates of desire,

if she had not dropped to her knees before even the least and shabbiest of temptations; if she had not been so much a part

and product of her times, of the confused or dissolving codes, the rush to modernity with its glorified standards of living

clambering ever up; if she had not acted always in the service of her own idolatry and had been able to reach beyond her own

moment in time into the moments of others, and into the future; then she might have recognized both her insignificance and

her importance.

It’s a remarkable achievement.

|