“As an artist I think and work graphically - in line and predominantly in

black and white. Drawing is to all other art as nudes are to clothed figures and as skeletal structure is to muscle

and fur. By observing well enough to draw something, one learns to identify weight-bearing structures, begins to understand

the lines of force, and discern the relationships among objects. For me, it begins with field studies; going out into

the cold and heat, dealing with biting insects - sketchbook in hand, learning to draw the twists and turns characteristic

of a cedar or the unique ways in which only a bur oak branches. Catfish tails fork in ways which those of carp do not

and the operculum of a trout functions very differently in pumping water through its gills than do the spiracles of a lamprey.

As these structures and their visual clues become second nature, I take this growing work into the studio and begin to invent

plausible creatures that fit into compositions with symbolic content.” ~Ladislav

Hanka

|

| "Bowfin: Native American Lungfish" by Ladislav Hanka |

Ladislav

Hanka: Artist Bio

I make my living

as an artist—drawings, etchings and book arts—occasionally straying into wood engraving and illustration. I have

work in 85 public collections and a record of something more than 100 one-man shows, plus eight traveling shows and a well-appointed

natural history museum in Belize to show for those 30 years of effort. The peregrinations of these shows have taken my artwork

from our Great Lakes to the yet greater Lake Baikal in Siberia and to many points in between. The archive of my life’s

work is housed in special collections at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

I have academic

credentials, but I backed away from that world long ago: There is an MS in zoology; MFA in printmaking and some years of study

in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic. I apprenticed with an engraver of stamps and currency in Prague and might have

been a counterfeiter, but for the dreariness of spending one’s days making money.

~Submitted by Ladislav Hanka for ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where his work will be shown at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, 101 Monroe Center, Grand Rapids,

Mich. 49503

|

| Ladislav in his kitchen preparing Turkish coffee |

Talking to Ladislav

by Zinta Aistars

I’ve

been here before. As I pull into the hidden driveway, yes, of course, I recall being here, at this house just off Oakland

Drive in Kalamazoo, Michigan, just a few months ago—but that is not what I mean. What I mean, well, I’m not sure.

It’s that mystic sense of déjà vu, perhaps, or a sense of place that opens and enfolds with welcome. I have arrived

at the home and studio of Ladislav Hanka, artist, printmaker, draftsman and book artist.

It’s

not the sort of house you are imagining, I’m sure. Not the residential abode in suburbia, not the rural place tucked

away for a hermit, for Ladislav extends welcome easily, and he lives here with his wife, Jana Hanka, also an artist. No, the

place is something in between, or out of parameters completely, an island alone, situated somewhere between the downtown of

Kalamazoo and its outlying neighborhoods. There is nothing manicured about it. Wildflowers grow along the painted fence, trees

fill space, of course there would be trees, and the corner lot is oddly quiet and peaceful, even though not removed.

No mistaking

that artists live here. The barn of a garage has murals painted on it, stallions gallop across the wall of the barn, and color

bleeds from everywhere, natural or made so. I find Ladislav squatting near the open barn door, working away at what appears

to be a wooden frame. He turns a tanned face toward me as I approach, and smiles.

He is opening

up space for a workshop, he explains. ArtPrize is approaching, the second annual art competition in Grand Rapids, an hour north of Kalamazoo, and Ladislav is preparing

an etching that will require some 40 square feet of space.

|

| Ladislav serves Turkish coffee with cardemom in cups made by wife Jana. |

Ladislav touches

my shoulder lightly as we move toward the house in the summer sun, remarking on my breezy summer shirt. I explain it is Indian,

purchased recently in an outdoor market in Washington D.C., just right for such a summer day, shimmering with heat. An intimacy

is established with that glancing touch. I feel welcome here. I feel, somehow, instantly known. There’s that sense again

… as if entering a space of spirits, of the mystical, and it doesn’t surprise me at all that our conversation

opens with talk of spirits, other lives, reincarnation, and ghosts, some of which, Ladislav explains, inhabit this house.

He offers coffee

as I arrange my notebooks on the kitchen table. I say no, thank you. Too hot, have had enough already. He makes it anyway,

a small smile on his face. My eyes wander over the kitchen as he prepares it, not in a coffeemaker, but stirring something

in a pot. There are horses on the kitchen walls. Zebra stripes wave and shimmer across the cupboards and ceiling. Huge butterflies

settle on the walls. A piece of driftwood hangs down from the ceiling. Color, everywhere. Life, everywhere. Unspoken rules

broken, everywhere. The Hankas live as their artists’ hearts lead them. I like it here.

We talk, and

I can hardly keep up making notes, as thoughts race and unwind and take off on tangents. I scribble to keep up with Ladislav’s

mind, only after some time noticing that I have drunk the Turkish coffee I had earlier refused, drunk my cup dry, and again,

and he keeps getting up to make more and refill it. I am suddenly aware that he somehow knew I wanted coffee when I did not

know I wanted it. I am aware that this is the best coffee I have ever tasted.

“It’s

the cardamom,” he explains, that hint of a smile there again, but I feel it’s something more. I can’t name

it.

Ladislav

Hanka was born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 1952, the son of immigrants from Stalinist Czechoslovakia, growing up bilingual, later

acquiring other languages, including my own native Latvian. He also speaks Russian, German, and he speaks the language of

trees, insects, plants, and not just because he has a degree in zoology. Ladislav Hanka is zoologist turned artist, or perhaps

intertwined, a kind of Audubon, only gone farther, deeper, beyond recording of life detail and into the realm of capturing

the spirit of the living in his work.

What emerges

is something in the art and artist both that emanates peace. It is the peace of a thing that knows its place, has given up

struggle, and accepted its place. Struggle may be in perfecting the art, but it is not an effort of resistance, rather moving

into a thing, observing it, watching it for so long and from so many angles, that at some point two have become one, one form

of life, without boundary. I think of Georgia O’Keeffe and her mountain, the Pedernal, just outside of Santa Fe, New

Mexico. Georgia had said that the mountain had become hers, because she had painted it so many times, in so many ways, that

God just had to hand it over to her.

“I must

draw the tree over and over again,” echoes Ladislav. “Draw it until I own it. Draw it until you can start to invent

that sassafras tree, you become the tree, you can start to improvise, can go beyond the tree and create it as a new tree,

your tree.”

If you look

at a tree long enough, he says, if you get to know it well enough, if you meditate on it, you begin to hear its heartbeat.

For every living thing, Ladislav says, has a heartbeat. Has a rhythm. Look at it long enough, and you begin to perceive the

life blood of trees, enter into that other state, something transcendent beyond ourselves, and from that comes a creation

of something new… of something we call art.

|

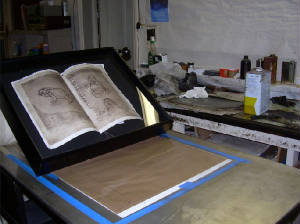

| Ladislav's studio and book with frogs |

Science and

art—Ladislav has been interested in both since, well, always. The two mesh well for him. At times, he had been interested

in one more than the other, switching back and forth, until the two combined into what became his art. “Life keeps pushing

at you for meaning,” he says, and this was what life pushed him to become, an artist who puts the accuracy and precision

of science into his drawings. He was a kid “who always wanted to get my hands on frogs.” He was curious, driven,

and putting his hands on frogs helped him to understand—frogs. And art.

Ladislav’s

artistic journey began before his own lifetime. That is, this lifetime. He speaks of reincarnation with conviction and ease,

even as he has seen those ghosts that walk his house and doesn’t mind their presence. “We all seem to remember

being Cleopatra,” he chuckles, “but that could be because we may all have been Cleopatra. The memory of genes

and generations.”

I get it. I

sip my Turkish coffee, empty again, and contemplate how one person may not necessarily be reincarnated as a whole other person,

but that that given bunching of genes is in one lifetime this person and then separates into a thousand, million, trillion

other persons in that many other configurations. I take a deep breath, push my empty cup toward him for more, and listen.

Ladislav’s

grandfather walked across Albania six times, and he kept diaries illustrated with watercolors. He was proclaimed dead of malaria,

then “rose from the dead” with a gasp, not dead at all. His diaries are inscribed with stories of walking toward

a light and being turned away, because it wasn’t his time. There is a peace that comes from knowing that. You die when

you should, and when you shouldn’t, you don’t.

Ladislav grew

up on such stories. Stories about his grandfather’s years in a gulag during the Stalin years. He met his grandfather

only in 1966, traveling to then Czechoslovakia to hear his stories in person. Stories about prisoners working together to

help one chosen prisoner escape and take their messages out to the free world. Those were such stories of suffering and horror,

however, that few in the world then wanted to believe them. Surely such cruelty as the gulag couldn’t be real. Only

time would prove it so.

His grandmother’s

stories were about prophecies and predictions, tales of the future, a whirlwind of events that no one wanted to believe…

until such things began to happen.

“These

were all formative stories,” Ladislav says, and he learned “that nothing is as it seems. I grew up with this mystic

view of things, and that art and mysticism are connected. I was born with the veil not completely drawn.”

It

is helpful to be around people who take you seriously, he says, but I am struck with this man’s ease in his own being,

something that surely must be taken seriously, and that otherworldliness in his art—a great many have taken that art

seriously, with 85 collections holding Ladislav’s work worldwide, museums exhibiting his work in this and other countries.

Seriously enough that he, unlike most artists, can make a living from his art.

|

| Jana Hanka with her horse sculptures |

“Many

live their lives out of fear,” he says, “and settle for security, yet at a deeper level long for that joy and

openness of a child. We should be that open, to wake up each morning like a child.”

Moving from

the kitchen into his studio, which is, not surprisingly, the largest room in the house and its center, we speak of the grace

and gracefulness of the aging. “When we grow older, we settle into acceptance, enjoy what is here, now, enjoy the moment

and stop working all the angles so much, always planning a future … [when we are young] we too often choose variety

over joy, always doing something to keep ourselves entertained, the monkey brain chattering …”

There is purpose

in boredom, he says, a need for “boredom” that opens into a space where we can create. “We all need to do

things that are meaningful. If you don’t find it one place, you look for it elsewhere. Young artists tend to be too

busy, wanting always to connect with others.” For him, Ladislav says, being at peace is a necessary first to create.

He needs to get all else done, put away. “I’m not that bull kind of a man that must fuck and fight. I create out

of peace, and quiet.”

|

| Ladislav in his studio |

From Ladislav’s

studio, we move into a tiny living room, where shelves and walls and floors and tables are filled with wife Jana’s ceramics

and sculptures. More horses, heads thrown back and mouths open, so that I can almost hear their whinny, their neigh, their

echo across time, galloping the earth. For a while, Jana joins us, and our talk veers to time spent in Latvia. I share my

own travel plans, that I will be returning after a long absence this very September, and Jana presses ceramic coins into my

hands, each one glazed a different color, each one with a hole in it for something to pass through … air, spirit, blessing.

I will bring them along, I tell her, and leave them there, where I sense it right to do so. On a tree limb, in the grass,

in the white sands of the Baltic.

Ladislav and

I talk about his own five-week journey through Latvia in 2005, with fellow artist (see The Smoking Poet, Summer 2010 Issue) Sniedze Rungis. “We drove across the country in a rust bucket of a car. There’s a good earth energy there. It

felt like home. An intense place with gorgeous energies. There is something in Latvia that I haven’t encountered anywhere

else…”

I hold Jana’s

ceramic coins in my palm, warming them, rubbing my thumb over their glazed surfaces, imagining Ladislav’s Latvia, and

my own, soon to be seen again, my own energies realigned with those of ancestors who shared my gene pool from so many, many

generations ago. There will be more stories to mold us. Stories that we will each attempt to hear fully and then translate

into our art.

|

| Jana's ceramic coins |

|