Talking to Gail Griffin

by Kate Lutes

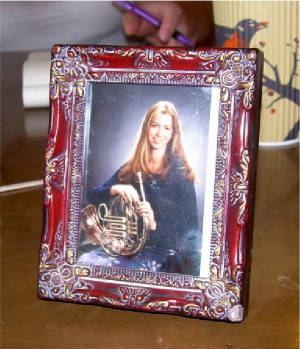

Dr. Gail Griffin carries a small portrait of Maggie Wardle with her when she interviews for her new book, The Events of October: Murder-suicide

on a Small Campus, published by Wayne State University Press (September 2010). As we sit down to talk at a local coffee

shop, she sets the portrait on the table between us. Maggie is beautiful; she has long hair and an energized smile –

it’s hard to believe that she was the victim of such a horrific crime.

|

| Maggie Wardle |

In October 1999, Maggie Wardle, a student at Kalamazoo College, a small, liberal arts school in southwest Michigan, was shot and killed by her ex-boyfriend, Neenef Odah, who then killed

himself. Nothing like that had ever occurred at Kalamazoo before; the student body consists of 1,200 students, the campus

is less than a half-mile long in any direction – unsurprisingly, the college community is very close-knit. Any disturbance

in its peace, and everyone quakes. And once the news spread about Maggie and Neenef’s deaths, the college trembled.

The Events of October offers numerous personal accounts of how the murder-suicide came to pass and

its aftermath. And who better to gather these stories to write the book but Gail Griffin? Gail is a Kalamazoo College professor,

and a scholar with wide-reaching interests, including women’s studies and Victorian culture. She received her Bachelor’s

in English at Northwestern in 1972, and then went on to get her Master’s and doctorate in English at University of Virginia

in 1974 and 1977, respectively. She took a professor job at Kalamazoo College within a month of finishing her doctorate, and

has been teaching there ever since. She teaches a range of classes at Kalamazoo, including Victorian literature, Creative

Nonfiction, and women’s studies courses. She has published two books of essays, Calling: Essays on Teaching in the

Mother Tongue (1992) and Season of the Witch: Border Lines, Marginal Notes (1995), as well as poetry and various

academic articles.

I did not meet Gail until my senior year at Kalamazoo College, first as my thesis advisor, and then again in the classroom.

However, I knew her long before that: given that the college can be a roiling, social hot box due to its size, Gail’s

reputation preceded her like a presidential motorcade. She’s respected by many students, particularly those who cross

her path in the English department, because she is deeply thoughtful, straightforward, and highly knowledgeable in many subjects

(not least of all, Johnny Depp).

Gail was the director of the women’s studies program in 1999, as well as the advisor for the campus Women’s

Resource Center when Neenef killed both Maggie and himself. Although she did not know either student personally, she (like

so many others) was deeply moved by the tragedy. She played an integral role in the Task Force on Violence Against Women,

and supervised the members of the Women’s Resource Center as they worked to inform and support the college community

during such a confusing, tragic time.

|

| Gail Griffin |

Several years passed before Gail began to write about Neenef and Maggie. “I said

to myself, ‘[This book] needs to be really soon or not at all,’” said Gail. A strong influence in writing

the book was the movie, Capote, which recounted how author Truman Capote capitalized on the story of two small-town murderers,

gaining fame in the literary world with the novel, In Cold Blood. While certainly Gail’s intent was never to take advantage

of a horrific event like the Kalamazoo College murder-suicide, she said that Capote’s story “just blew me away.”

Capote had taken a true account, one that not many would dare to seek out, and made it into a compelling narrative. “I

was galvanized. I knew then I was going to do the Maggie Wardle story.”

The most important facet of The Events of October is the numerous voices

that Gail includes. Throughout the book, we hear from college faculty and administrators, Maggie’s family, and both

students’ friends, each adding one more element to the narrative Gail aims to construct. Then-president Jimmy Jones

honed the chaos into a cautionary tale about gun control in America. He, above all, had to create a coherent account as the

head of Kalamazoo College, and that no doubt tied his hands more than he wanted. (Gail describes Jones with a great amount

of sensitivity – watching him react to the murder-suicide is heart-wrenching, considering how bright and amiable we

understand him to be.) Friends of Neenef Odah wanted the world to remember him as they did: a loveable boy who was brought

down by despair and depression, not a man destined for murder.

We also hear Gail’s voice as she details to her readers statistics about intimate partner violence. Each person

has his or her own perspective or agenda, and, when brought together on the page, illuminates an event that had lied in obscurity

for a long time. While she admits the subjectivity of her own perspective, her overall narrative has a collective truthfulness

to it – she remains an individual who witnessed these events, but also represents those with whom she connected during

those times, as well as ten years later while writing The Events of October.

“I never question interviewees’ opinions,” she said. We as writers can be faithful to those involved;

we can respect the truth and narrate a story without invention, and we can allow multiple, even conflicting, stories to work

together. Gail ended this train of thought with a quote from the movie, Pirates of the Caribbean (featuring Johnny Depp):

“Different versions – all are true!”

There’s Jeff Hopcian, who had been waiting for Maggie downstairs in DeWaters Hall, who walked into the

bathroom and saw what he saw, who staggered through his life for the next weeks, trying to be okay, trying to get back to

normal and pass his classes, until pressure from his choral director cracked the dike. Jeff, whose friend said that

after October 18th his eyes weren’t the same. Another friend remembered talking to him at a party later that year and

realizing he was “marked.”

Whose eyes wouldn’t have changed, seeing what he saw? Who wouldn’t have been marked? Yet Jeff was

somewhat embarrassed by his friends’ memories of him. He felt less entitled to his damage than others. What about

her parents, and his? he asked me. What is my wound, compared to theirs?

One reason suffering is so hard is that gets comparative, or competitive, or guilty. What could we have done,

I wonder--as people, as a college community--to convince ourselves that whatever effect these deaths had was legitimate, real,

to be honored and suffered and solaced? That all of us were survivors?

“The test of an institution is how you respond to [intimate partner violence],” said Gail. The Events of

October also recounts how Kalamazoo College as a community and an institution reacted to Maggie and Neenef’s deaths.

Although there was an initial call by the college for a task force for intimate partner violence awareness, that drive diminished

and eventually was lost in the transfer to a new president (although not for a lack of concern or diligence on the part of

the new administration). Gail added, “A woman had to die in order for it [intimate partner violence] to be an issue

for six months, twelve months.”

|

| Kate Lutes interviews Gail Griffin |

That sentence, like many that I heard Gail say during the interview, pulverized me like a wrecking ball. Maggie Wardle’s

life was full of ambition, action, and sympathy, and reading her story was like talking to my college friends. Was I shocked

to see Maggie associate with a guy like Neenef – immature, prone to moodiness and insecurity, brilliant but bogged down?

No, because I have experienced and have been told that story often during my career at Kalamazoo. How many times have we women

excused men’s poor behavior as harmless, because no one was physically hurt? Why is this okay?

Another truism from Gail: “The last thing a woman learns is how to set boundaries.” Society has encouraged

women to be compassionate without limits – in order to be good-hearted, one must always acquiesce. “Somehow [women]

need to get beyond compassion and empathy [as incompatible to] boundaries.” Without boundaries, women can find themselves

in abusive relationships, where their partner takes advantage of them both emotionally and physically. We’ve accepted

violence towards women for so long, it’s ubiquitous in our culture, found even in popular music:

Just a few weeks later, I am happily immersed in early Beatles when I hear for the

first time lines that I’ve known since I was thirteen:

Well, I’d rather see

you dead, little girl,

Than to see you with another man;

You’d better keep your head, little girl,

Or I won’t know where I am.

You better run for your life if you can, little girl,

Hide your head in the sand, little

girl,

Catch you with another man,

That’s the end,

little girl.

This was our soundtrack—what we danced to, cruised to, got high to, got laid to. How deeply woven

into our cultural consciousness this is, I think, this “romantic” plot of the man “driven mad” by

jealousy who murders his lover. How deeply was this story imprinted in me? How often does a kid need to hear different

versions of a song before that kid has it, as they say, by heart?

|

| Maggie Wardle and Gail Griffin |

I interviewed Gail at a local coffee shop, usually a good spot to talk, but for this book, this subject, the atmosphere

seemed antithetical. We came here to discuss The Events of October and the deaths of two college students, but the other customers

laughing and conversing around us reminded us that life was moving onward, despite our best efforts. With Maggie’s smiling

portrait on the table, a stranger might think we’re talking about a young relative of Gail’s who went off to college.

When we finished the interview, I was moved and enlightened, yet a little terrified like everyone is when faced with a

revelation. But I don’t regret diving in: both The Events of October and its author have begged more questions that

need answers. Not only from me, but from society. These are big questions not easily resolved, but they are now posed to the

general public, joined by others from similar narratives. Perhaps like those of the rock music of Gail’s youth, the

themes of The Events of October – intimate partner violence, boundaries, community support, truth – will start

to gel in our minds.

|