|

by Zinta Aistars

|

| Jeanne Hess with Guinnez at Z Acres |

Jeanne Hess is a walking blessing. I have

known this for years, fully the eleven years that I, too, worked at Kalamazoo College, where I first met Jeanne. Jeanne was,

and still is, a professor and head volleyball coach. She was also college chaplain for some of that time.

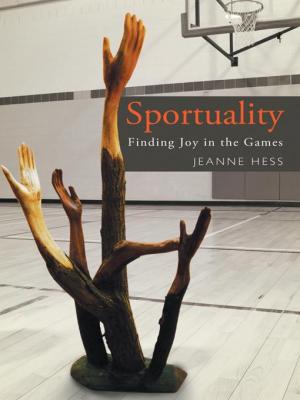

Sports and spirituality … an interesting

combination. For Jeanne, the two are so well meshed, that the title and topic of her new book is: Sportuality, Finding Joy in the Games.

I'll put this right out here, right at the

start—I am not much of a sports fan. And yet, interestingly enough, as Jeanne and I sat down in my farmhouse kitchen

to chat over a couple of hot mugs of tea, I told her that many of my favorite movies and favorite stories were about sports

figures. How can that be?

A hero's quest, we determined. Sports make

good stories. A human being striving to reach excellence, in body and in mind. Yet when we watch sports on the television,

or at a ballpark or arena, what we see around us often more resembles two teams at war. That, I realized in reading Jeanne's

book, is what had alienated me.

Jeanne writes in the introduction to Sportuality: "I challenge the way our culture uses sport to promote and sustain a war-based paradigm … Sportuality explores the true meaning and etymology of words such as competition,

spirit, inspiration, conspiracy, humor, enthusiasm, and others. By reaching back to the roots of these words, Sportuality examines how they have been corrupted by modern usage, a revelation that enables the stories to take

on a meaning different from current cultural values."

|

| Circle of volleyball love at Kalamazoo College |

Here's where I get on board. I am a writer, I love words. I understand words.

I found myself fascinated by this book, and fascinated as well by the author, who lives what she writes and embodies sportuality

in her person.

Without thinking about it, I responded to what my own spirit nudged me to

do as Jeanne walked through Z Acres with me, sharing my ten acres of woods and fields and pond, and my century-old little

red farmhouse. I asked her to bless this place.

"It's already blessed," she said. And I couldn't argue. This place had come

into my life by divine intervention, no other explanation for it, through a series of puzzle pieces falling so neatly, so

perfectly into place, that chance and circumstance were no explanation. I had felt that blessing from the moment I discovered

this, my slice of heaven on earth.

Still, I wanted Jeanne to bring blessing on it with a shared prayer. Something

official. We stood out on my back deck, under the tree cover, facing the fields that stretched far out to the tree line beyond,

and she raised up her hands, palms to the sky, and asked for a blessing on this place. As I listened to her, tears streamed

down my face, I was so moved by her words of prayer, and Jeanne's eyes filled, too.

Next moment, we were on sports again. Maybe

Jeanne's right. Sports, spirit, blended.

"Teams have spirit," she writes. "God intends

for us to have fun and be playful; that's why humans created sport, initially for primal hunting and today as games played

by teams in organized leagues."

Anyone who has watched a sports game knows

that games begin with prayer. Teams are told to have spirit. Athletes are encouraged to rise above who they are in physical

body alone, to win over physical limitations, to endure and overcome.

How did Jeanne come to this unique approach

of combining spirit and sport?

She told me a story about her aunt, a nun.

"She was a wonderful, crazy, radical nun. She listened to the voice of God rather than the voice of Man around her."

Jeanne's aunt put her habit on the girl's

head, and said: "I know you won't be a nun … but carry on my work." And Jeanne has. "I've always had that God piece,"

she said.

Kalamazoo College recognized that God piece

in Jeanne in 2001. A tragedy hit the small liberal arts college campus. A male student, riddled with jealousy over seeing

an ex-girlfriend dancing with another young man, shot and killed her, then shot himself. The

campus was mired in grief, Jeanne said, and was in need of healing. Jeanne seemed to be the right person to offer that healing.

Retelling that story, her eyes fill with tears. Healing, after all, can take a lifetime. She rose to the occasion, became

college chaplain, but maintained her position as coach and physical education professor, too.

|

| Jeanne at an author's reading, Michigan News Agency in Kalamazoo |

One of her first official tasks was to offer

healing again when the United States reeled after 9/11, a terrorist attack taking down two towers filled with people in New

York City.

"I was overwhelmed like anyone else. I created

a team of ordained people from every faith as a team," she said. The college

began an interfaith dialogue, and Jeanne guided students and staff to understand the concept of our connection.

To listen to her coach her volleyball teams

is not so very different. She coaches her students to understand their connection. Not only to each other on their team, but

also to the opposing team.

"Sport is a vehicle for how we live life.

Sport is a vehicle for ultimate human communication," she writes. And competition between two teams is actually bringing the

best out of each other—not to annihilate each other.

Healing, coaching, ministering, encouraging,

empowering—Jeanne does all this no matter if she is courtside or in front of a congregation. The lines blur, and perhaps

don't exist at all.

As for being a coach for teams of young women,

Jeanne says sports have done much to empower women. She's spent nearly 30 years coaching, and her teams relate to her with

a team spirit that really does … rise above.

By the time Jeanne left Z Acres, I felt as

if the entire acreage shimmered with a new light. Blessed, yes. I felt that I was, to have had Jeanne visit me here, and to

have shared a few hours of her time, deepening our friendship, clearing the spirit for more work ahead.

|

| Jeanne with sons, both played in the Detroit Tigers organization: Andrew (r), Kevan (l) |

|