|

|

| Conrad Hilberry |

Talking to Conrad Hilberry

by Zinta Aistars

Without exception,

I have yet to meet anyone that wouldn’t describe Conrad Hilberry, or Con, as “gentle.” Such a kind and gentle

spirit, people say. And he is. Conrad Hilberry emanates gentleness and gentility, he is a gentleman to the core, and there

is nothing about him that isn’t gentle … except his poetry.

When I arrive

at Con’s condominium in Kalamazoo, Michigan, he smiles as if I were the person he wanted to see most in the world. Which

surely I am not, with my intrusion into this sunny day when he would no doubt rather be biking, or sitting at his desk

musing over a new poem, or any number of gentle pursuits. Yet he makes me feel utterly welcome, and I can’t help thinking

of how much he reminds me of my grandfather, also a writer, etched unchanged now by time since he has passed, tall, gaunt,

endlessly energetic, and gentle.

Without pausing

to think, I give him a hug. He chuckles softly and leads me into his spotless home and invites me to be seated, where he has

already placed a few new poems on the table, and a bowl of pistachios and another bowl for their shells, and another bowl

of grapes.

Yet I sense

this is all rather uncomfortable for him—to talk about himself. Conrad Hilberry is a much beloved professor emeritus

of English at Kalamazoo College (1962 to 1998), where he is still seen on campus, and often, and still teaching. He teaches adult poetry groups, and interacts

with students, appears at the Hilberry Symposium, a gathering of young writers in his honor. It is the rare literary event

on the college campus where Con isn’t present in the room, listening attentively, smiling his gentle smile. Indeed,

he appears all over the Kalamazoo community at literary events, book stores, libraries, anything that has anything to

do with fine literature.

Conrad Hilberry

was born in 1928 in the small town of Ferndale, Michigan. He earned his undergraduate degree at Oberlin College, went on for

his graduate degrees at University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of nine books of poetry and also a nonfiction first-person

narrative of two sociopaths in Kalamazoo, called Luke Karamazov.

Wait …

two sociopaths? Why would such a gentle spirit be interested in writing about weapons, murder, cruelty? Are we talking about

the same Conrad Hilberry?

We are. For

there is that gentle spirit we Con fans know, but there is also that quiet passion, the fire that comes through in his literary

work, as well as the dedication he has to teaching. We sense it, too, when we see him biking, and not just a Sunday pedal

around the block, but for miles, helmet pulled low, bent forward for speed. At poetry readings, he gets up behind the mic,

then starts to read … and we instantly see and hear: there is much more to this poet than that easy smile and that soft

chuckle. Much more.

I am tired of mothers and their milky ways,

of babies sticky as figs. I have left a kingdom

of them. There must be some truth beyond

this sucking and growing and wasting away.

A star should lead an old man, you would think,

to some geometry, some right triangle

whose legs never slip or warp or aspire

to become the hypotenuse…

(from “Wise Man,” in the poetry collection

After-Music)

And there it

is—that inner fire, as if flames peeking through the windows of a man’s eyes, flickering inside, suddenly blazing

and sending up sparks. It is that place, that secret place, from which arises great poetry and the passion necessary to write

it. He was also one of the editors for the three Third Coast anthologies of Michigan

poetry published by Wayne State University Press, and his musical, co-written with Merwin Lewis, Beggar Moon, was performed at the Kalamazoo Festival Playhouse.

“Pistachios?”

he pushes the bowl toward me. I snap one nut open.

What is he

working on today? I ask, and of course, there is always something. A chapbook is being developed by the Kalamazoo Book Arts

Project, and Con pushes the pages of new poems toward me. I am expecting a profound response when I ask how he became a poet.

“I’m

not very good at other things,” Con says, and smiles, and shrugs. “Words are what I play with … there is

no danger of my becoming a painter or a musician.”

Richard Wilbur

and Tony Hoagland were his favorites, and he developed favorites among the up and coming, too. Diane Seuss (see The Smoking Poet, Spring 2010 Issue), award-winning and comet-rising poet (Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open is her

latest) is Con’s protégé, a high school kid he discovered in the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it town of Niles, Michigan.

He speaks about her, Di’s talent, with even more passion and certainly more comfort, than he speaks about his own. He

was, he says, in the presence of budding greatness when he heard that high school girl read her poems. Diane Seuss is now

permanent writer-in-residence at Kalamazoo College.

What makes

a great poem? I expect another chuckle, a mischievous glint in the eye, but this time Con Hilberry is serious, thoughtful.

“It must

be understandable. I don’t want to have to puzzle it out. It must be so personal that I feel I know the poet when I

read it … imaginative, creative, written with care and skill … and with an ending that just socks you.”

His own poetry,

he admits, is more revision than not. Sometimes Con writes in a style of stream of consciousness, then picks out the lines

that work and intrigue, and then polishes those. Sometimes he reads older material, thinking it is finished, only to find

that it could use revision—and he gives it another go.

“The

first step of editing is always to know what to leave out.”

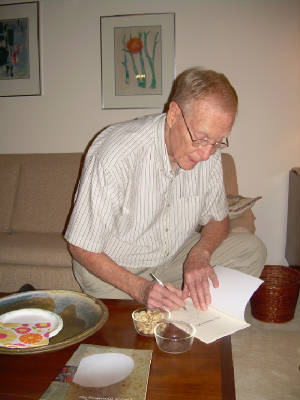

|

| Con inscribes a copy of After-Music for me... |

His own work

that he enjoys the most, Con says, are the “object poems” found in his collection After-Music (Wayne State University Press, 2008). This is a series of poems as if in the voices of inanimate objects—an alarm

clock, an oboe, an egg, a slice of cherry pie. “It was a relief to speak as something else, a lot of fun to be

a piece of cherry pie, so cheerful, you know, with all that whipped cream on top …”

We’re all acquainted with the airy

crowd—a stalk of celery dipped

in cottage cheese, a thimble

of soy milk, a few green grapes.

I invite them over here: between

two butter crusts, my sour

flesh so deeply sugared it

astounds the mouth.

To coax it all to bed, a downy

pillow of whipped cream.

Try me, you organics.

Light the oven.

Let me show you how

the juices leap, when nature

shares the sheets with art.

|

| Father and daughter, fellow poets: Jane and Conrad Hilberry |

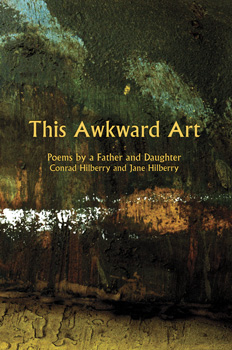

Another special

poetry project has been to share his work with that of his daughter, Jane Hilberry, professor of English at Colorado College.

This Awkward Art (Mayapple Press, 2009) is a collaboration between father and daughter, about which Jane says:

“About the book project, the idea arose after my father and I gave some readings together. We organized

the readings the way the book is organized, in thematic sections, so that the poems could speak to each other. I think

we were both surprised to find that we use many of the

same images, and that although our styles are very different, the

poems did seem to work together. When we were putting together the book, we even discovered that we'd each written poems

about the same painting by Vermeer. So the process was that we wrote the poems separately, then arranged them so that

they would resonate with one another.

“When I was young, I think I tried to write like my dad, because

I admired his poems so much, then I tried to NOT write like my dad, because I needed to feel that I had a separate voice and

identity. Now, later in both of our lives, it's great to be able to bring our poems together and know that we're each

writing in our own way, but that our poems also belong together, partly because our sensibilities do overlap, and also because

we have common family experiences, including my sister's death at age nine and my mother's death a few years ago. It

feels very good to have our poems together.”

|

| Con's bike and helmet, awaiting the next ride |

Two other Hilberry

daughters, Ann and Marilyn, share a love for books and teaching, the former teaching at University of Michigan, the latter

a librarian at University of Massachusetts-Boston. That bond between loving literature and sharing that love with others

is a clear mark of the Hilberry family. “Teaching is not to stand up at front of the classroom and talk,” Con

says. “It’s more about asking questions and listening. I can’t think of anything more stimulating than teaching.

I’ve never wanted to leave that to retire …”

Yet he does

leave it, now and then, and often that leaving takes place on a bike. Con misses his wife of 57 years, his “first eyes”

on his poems, Marion, who passed away two years ago, but he hasn’t let that grief slow him down. In February 2011, he

will tour Cancun on a bike with a group called The Road Scholars. Thirty, forty, fifty miles on a bike each day, sure, why

not. Sometimes, he says, such trips inspire to new poetry. Sometimes, he chuckles, it’s just a respite, a long ride

from sunrise to sunset. You can keep riding forever. It’s just a matter of finding that gentle but steady

pace.

|