|

Vacancies

by Colleen Kolhoff Little

If the forgotten road sits on the ridge of your

spine, the gnaw under your skin is untying you and the miles ribboning out beckons for the name of things; of towns, and cities

leaning in. Riga, Teapot Dome, Climax. It’s absurd you should never leave home or hurl yourself into the shadows of

green forests furred in snow or of silver buildings climbing the sky. Here you must ease yourself into the mouth of Grand

Rapids, Detroit, and Kalamazoo. Amen & amen again for the vacancies on the shore, and the greatness of lakes. Your misgivings

when you leave Saugatuck, Grand Haven, and Traverse City will dislodge you like a rolling stone. Move in to the peril of another

travel to a bridge holding on like teeth from earth to earth, visit the ghosts of Keweenaw, the Peninsula of Copper and the

filigreed light of another sunrise, another sunset pushing you forward, pulling you out of your wrinkled sheets. Just open

your hand and point to where you are, where you’d like to be, and you’ll be there.

Colleen Kolhoff Little is a writer

and artist living in Kalamazoo, Michigan. She has won several writing awards, The Kalamazoo Gazette Community Literary Awards

and the New Century Writer Awards. Her work has appeared in Red River Review, Aesthetica, Verbicide, Poems Niederngasse,

Red Lion Square, and Short, Fast, and Deadly.

Gabbatha

by Rick Chambers

Inside jokes were the best thing

about time travel.

Subtly slipping himself into

an ancient work of art or a bit of classical literature never failed to amuse Rhys Timofey. But he stopped after two screwups—letting

a woman play with his cell phone in a 1928 film, and forgetting to remove his Oakleys for a newspaper photo in 1940. Both

incidents caused brief Internet uproars decades later.

There was another reason to

cease his cameos: It never occurred to him that one's biology might be anchored to one's place in time. Weigh that anchor,

and cumulative damage occurred.

Deep in the introspective haze

from a Dvin brandy, which he shared with Churchill at Yalta, Timofey figured he could survive one last journey: returning

to his own time, or making a permanent home in the past.

The decision was surprisingly

easy.

A few hours later, Timofey stood

in a broad, paved courtyard, bathed in torch light beneath a cold night sky. He hugged himself, trying to keep warm. Across

the courtyard, wearing long tunics and loose-fitting coats, a handful of men huddled, murmuring among themselves. Timofey

knew what they were up to.

Turning, he beheld a stately

portico and the immense fortress from which it protruded. Made of stone and ringed with an ornate colonnade, the structure

spoke of wealth and power. Inside, Rhys knew, were walls painted with characters from mythology, intricate mosaic floors,

luxurious curtains, and sparse but expensive furniture.

Right now, those fancy walls

and tiled floors were bearing witness to a pivotal moment in history—a moment Timofey was there to change.

He was, of course, aware of

the dangers of tampering with history. Writers from Bradbury to Zemeckis had given ample warning, so much so that, in his

early travels, Timofey would check his shoes for stomped butterflies and steadfastly avoid contact with female ancestors.

But eventually he realized that time had a way of repairing itself, absorbing discontinuities as a pond absorbs ripples from

a tossed stone.

Actually changing history would

require a significant and carefully chosen act.

Rhys glanced toward the eastern

sky and its first hints of encroaching dawn. In a few minutes, a verdict would be delivered from the portico. That verdict

would be driven by politics, loud voices and veiled threats, standing for all time as the greatest travesty of justice in

human history. Timofey would not allow it to happen again.

The crowd was growing larger.

It was clear to Rhys that the men were acquaintances. This confirmed a lifelong suspicion. For a moment, he regretted that

he could no longer travel through time and admonish the millions yet unborn who would wrongly blame this injustice on an entire

culture rather than on a few conspirators.

Blame ...

The word lodged in his mind,

nestling against a centuries-old question: How was it possible? A few dozen men-cajoled, bullied, or merely self-seeking—had conjured

an epic wrong, one that would forever influence the course of history. It was hard to believe. Perhaps more was happening

here than a few voices demanding a verdict of guilty and a penalty of death.

But what? Rhys knew the account

of this moment. He'd studied every relevant text. The criminals were assembling; in minutes, they would assume their immoral

roles, begin the cruel choreography, and condemn an innocent man.

Innocent ...

Another word that wouldn't exit

his thoughts. It was a fascinating contrast, these two opposing words. He wasn't quite sure what it meant. He knew only what

was happening to that innocent man right now, somewhere beyond the portico: agony, humiliation, and deep sorrow.

The morning sun lifted itself

over the horizon, casting pale yellow rays upon the portico. As if on cue, a balding man, pink-cheeked and slightly pudgy

beneath his official-looking robe, emerged onto the platform. He carried himself regally—too much so, exaggerating his swagger as

if to underscore his position to a skeptical audience. He strode to the edge of the portico and stared at the crowd with unabashed

contempt.

Then he turned aside, allowing

someone else to join him.

The newcomer was a shuffling

ruin of a man. After hours of torture, he barely managed to stand upright. His legs quivered with unbearable pain and fatigue,

and his breath came in short, agonizing gasps. His face was a grotesque mask, peppered with cuts and nasty bruises. The plum-colored

cloth wrapped around his thin body was darkened with large splotches of blood. Crimson rivulets coursed down his face and

neck, flowing from a ring of braided thorns shoved cruelly upon his head.

The unfathomable grief that

glistened in his swollen eyes was perhaps the most pitiful thing of all.

The official gestured to the

new arrival, making sure every person in the astonished crowd got a good look at what was left of him.

"Idou ho Anthrōpos!"

he shouted. "Behold the man!"

Timofey did just that—and gasped in abject terror.

What he saw was no victim of

torture, no blameless captive awaiting a rescuer from across time. Instead, he beheld something unbearably hideous. It was

as if all that was Evil, from everywhere and everywhen, had been poured upon the man. Every ghastly thing done, every repulsive

thought entertained, it all ebbed and flowed and dribbled before Timofey's eyes. That such ugliness could exist, that God

Himself could tolerate it for an instant, was beyond comprehension. It was unrighteous, irredeemable, screaming to be destroyed.

And the deepest, soul-shaking

horror of the monster was that it looked just like Rhys Timofey-not just in appearance, but in his full nature. It was the

sum of his every deceit, his every unspeakable word or deed, his every fear and desperate act, a gruesome reflection of his

foolish and failed existence, laid bare for all to see.

Rhys searched for a hint of

decency in the thing, desperate for a glimmer of hope, a modicum of good-enough. He begged for it. He wept for it. But he

failed to summon that vision. He knew instinctively that something else needed to happen first. And here, at this crossroads

of time, this critical juncture of humanity's story, Rhys was witness to it.

To destroy the Evil, the Innocent

had embraced the Blame.

At last, the crowd roused itself.

The men began to shout, feeding a frenzy that burst through Timofey's shock and revulsion. He couldn't turn away from what

he saw. He couldn't demand justice as he'd planned, couldn't stand firm for what was right, couldn't defy the crowd that he

so hated.

Because the image he had seen,

he hated more.

And so he joined their cry.

He knew he must—for his

own sake, and for the sake of humanity, now and forever.

"Stauroo! Stauroo! Stauroo!

"

"Crucify."

"Crucify."

"CRUCIFY!"

Rick Chambers is an award-winning communications

professional and a former journalist. A lifelong science fiction fan, Rick is the author of the recently published SF novel

Radiance, as well as three novelettes and numerous short stories, many of which have won Community Literary Awards

and other honors. He is a writer and narrator for Chronicles, a direct-to-video/online series. Rick makes his home in Kalamazoo,

Michigan.

Elizabeth

Kerlikowske

A sort of Stonehenge.

The judge stood in the center.

Footprints in snow leading from the house were suspicious.

One way? I count the matchbooks. I know you took the Kroger’s. First the trellis. Now the coiled hose. You don’t

have the kind of face that can even shoplift safety pins. There is no drawer that

is a secret to me.

My secrets are sacrosanct. You wear too much black.

Some times you want to disappear into another like anthrax dust.

Quarter turn.

You are so small inside. Why are you so tall? Your

hair is too thin. Quit reading and look out the window. This is for your own good. Stand up straight. There is no secret path

from the fruit room to another world. No one is going to rescue you, so you can cut your hair. There’s no way to repay

your rescue from oblivion. Put on some shoes

Quarter turn.

You remind me of him, tanned strength in the fingers.

Sparse forest of black hair. Don’t give up.

You can do more than sprawl in that lunchbox. Get yourself a humidor. Sleep on the dic- tionary like Edgar Cayce and learn by osmosis. Don’t be-

lieve everything you read. They are all liars. Dictators. Practice your scales for dexterity. And find yourself an arm, for pity sake.

Quarter turn.

Silly, just silly. Less than a fly. An annoyance.

If I could trap you in The Pressed Fairie Book. Innocent dunce, delighted to be alive, in love with mosquitoes and light-

ning the same. No standards.

Sugar maple is never worn after June, sparklers

one July night only. Rules apply to you too. Stop that blinking. Get back here.

Dear

Diary

Dear alley and garbage so fresh on Wednesdays, dear

newspaper,

dear cat with no tail and one eye, dear dictionary

who said a foundling

is abandoned whereas an orphan is bereaved, dear

public education,

dear ladies who took it in and sat it in front of

a keyboard, expecting

music like lungs expect air, dear uniforms, dear

knee socks,

dearest hole in every big toe even if the socks switched

feet, dear bare

feet and calluses, dear dirt that coated its hide,

dear hide that held

its guts, dear guts that fed its hunger to soldier

on.

Elizabeth Kerlikowske hopes to spend time this summer exploring the shipwrecks of Lake Huron in Michigan.

Meanwhile, she'll be a barnstorming poet with the Binge project. She is the president of Friends of Poetry, Inc.

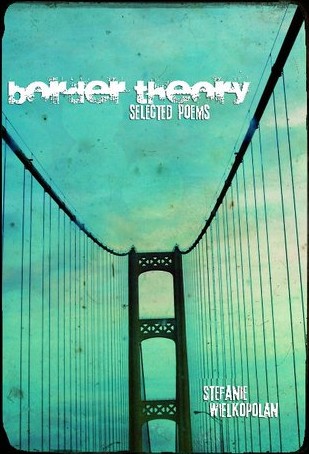

Border

Theory by Stefanie

Wielkopolan

Review by David Blaine

Paperback, 67 pages

Publisher: Black Coffee Press, 2011

Price: $9.95

ISBN: 978-0982744048

In the latest offering of verse from Black Coffee Press, Stefanie Wielkopolan

allows us to stow away on her personal journey through the life she’s lived so far.

At the start it feels like we are friends watching an old, eight-millimeter movie of her childhood, discovering the

parents, grandparents, siblings and friends who have all helped shape this poet into the woman she is today.

I immediately noticed the importance of place names in Wielkopolan’s

collection. Understanding that these sketches are rooted in specific times and

in definite locations, like Traverse City, Petoskey, or East Tawas, Michigan, are critical to my appreciation of her life

experience. She wields time and place like a credential, a factor that easily

convinces us to accept what she reveals as genuine.

In the poem, “In 1984” we glimpse one of the author’s memories

of her parent’s love.

“My parents loved each other. / …my father drank his coffee /

read the morning business page / as my mother walked into the kitchen / kissed each of us on the cheek / because she wanted

to / …As she packed my father’s lunch / she wrote I love you / on the peel of a banana and orange.”

And in “Circa 1983” we watch the four year-old author interact

with an unnamed friend of the family.

“What I want to say is I am sorry / for peeing on your head / that summer

we spent in East Tawas /…you were sixteen and I / was four / you pulled me up to your shoulders / as I waded out of

the lake /…My mother…/ handed me a towel. / I said thank you / then

peed / warm against your back / with a smile. / …I watched you in Lake Huron / as you washed your chest and arms / and

I was satisfied, knowing / you were mine.”

For me, the inclusion of such tidbits as the year, the author’s age,

and the place names, both of the town, and of the Great Lake, Huron, all add to my appreciation of this writing. As children, we are certainly shaped by our environment, and knowing that Wielkopolan has lived in Midwest

towns like Ann Arbor and Kalamazoo, this is a key that helps unlock a door in these poems. It allows us to visit the author’s

attic, so to speak; root about in the family photo album and perhaps better understand how the author became the person we’re

meeting within these pages.

In “We Sleep With Bears” we are told,

“When I strike a match I smell the campfire pit / charcoal / marshmallows

roasted / …We spend one week a year in Traverse City amongst cartoon bears and red tart cherries. One week a year.”

I know this place; it used to be called Jellystone Park. I’ve viewed it from a distance in July, when the National Cherry Festival is held, and I’ve

skied through it on cross-country tours, when tourists are but a fond winter memory.

The park itself is now a distant memory, renamed Timber Ridge, with a much more staid atmosphere than the raucous cartoon

themed campground of simpler times. But through Wielkopolan’s memory of

faux fur bears I feel like I was with her, back then, eating ripe cherries until I got a bellyache, or making S’mores

by a campfire.

Although the author doesn’t divide her book into sections per se, I

do sense at least three distinct groupings in her work. The first grouping seems to conclude around the time we read of her grandmother’s death in “Love

On Tenny Street.”

“…In separate rooms they whispered the word joy / but every afternoon

at lunch / there were no words of comfort. / Instead, we heard / You’re fat Catherine, stop eating that crap.

/ And the gentle response from our grandmother / Stop being mean, Grandpa. // And once our grandmother died / stories

of her wanting a divorce / long before I was born.”

After this poem the pieces begin to center around Detroit, although there

are still treks north. The author is a young adult now, and coming of age.

Through poems such as “Boyne Falls,” which I’ll include here in its entirety, we discover that tastes and

aromas have become as important to her as places and times.

“I wanted to believe that you loved me / when we stood / on Northern

Michigan ground. // Nothing but land that sloped / down to the lake and the pancakes / we ate for breakfast. // Snow, the

only thing to distract us, / blew in the hallway / as we carried our groceries / home. /Wine, avocado, and bread. // We fell

asleep that night. // We fell the next year. // Now I wake in a city, a bed of

broken warmth. / No forest in my suburbia or slope of land. / No evergreen or fire-scented bar / twenty miles down the road.

/ No cabin love, no wood burning oven. // This, the scent of your absence.”

Still learning about life and love through her observations of other people,

Wielkopolan makes an interesting point in “Pre-Packaged.”

“Spinning through the aisles I try to determine / which couple / is

most like you and me. / The annoyed girlfriend in the baking section / yelling at her partner / to buy the dairy-free cake

mix? / How many times do I have to tell you, asshole? I’m / lactose

intolerant! /…Whoever said it was the little acts / in a relationship / that make it work / was a liar.”

And then, as the author begins to write about learning to love through her

own trial and error, we come to “What We Repeat.”

“You call me from the road / tell me you

are ten minutes outside of Detroit. /

Two-hundred and seventy miles away. // I love you. // Goodbye. // See you next month. // This, our third winter of …toll roads and distance. // …I want to be in a wood cabin / alone with you

/ somewhere in Rhode Island where we / would smell of campfire and coffee. // …You say: One more year and we will

be together. // I answer: One more year / and whisper goodbye.”

While writing in a style that is reminiscent of William Carlos Williams’

“Nantucket,”

Wielkopolan takes a more indirect approach to intimacy in her own poem titled,

“Intimacy.”

“Left on the table / one ripe lime / a bottle of tequila…Sketches

of round bodies / serve as a coaster / for the empty shot glass. // A clear bowl of fruit / atop the philosophy book…”

“What We Repeat,” and “Intimacy,” precede several

other poems that expand on the same theme including, “My Brother-In-Law Calls Me a Whore” and “I Want to

Sleep with the King,” where the author visits Graceland and indulges in an Elvis fantasy.

I sense the final grouping in this book begins when the stories shift out

of the country and Wielkopolan writes a series of poems about her time in Germany.

In “When I Miss You the Most” a universal experience of long-distance

lovers comes to the fore.

“Above the food kiosk / a plaster model / Rostbratwurst / …I stand,

… / and stare at the wiener /…So phallic, I muse / and think of you. /…the bun / doesn’t even cover

/ the entire length / of the brazen link.”

And in “Shopping Center” the author finds that no matter how far

you travel, things don’t necessarily change much.

“At a shopping center in Berlin / which could have been any mall in

America / we shared a raspberry Danish…”

There are also poems about The Netherlands, and Mexico, in which the author

and her girlfriend toast comfortable cotton underwear. At the very end, traveling

about her own country again, she visits Kentucky in a poem titled, “Reasons to Dislike Your Mother.”

“…The shell of a turtle. / That’s what she called me. ?

Hollowed out / bones dry / no meat left / for you to suck on. // In the kitchen she taught me how to make dumplings. /…I

held a fork as she talked / …and cut through Kentucky. / Later I washed the wheat from my tongue / and drove north.”

It seems fitting that the book closes with this poem, and with Wielkopolan

heading north, back towards Michigan, back home.

This is a collection that you will treasure immensely. I am looking forward to following Wielkopolan’s work in the future.

You can order a copy of Border Theory from Black Coffee press.

David Blaine lives in the Michigan “thumb,” where he and his wife

Judy operate the state’s oldest hardware store. Dave’s writing has appeared on and off line in numerous small

press publications. He is a co-founder of The Outsider Writers Collective and enjoys good drinks, strong cigars, and reciting

poetry. David is a former cigar editor for The Smoking Poet.

Maris

Cohen

Genetics

There was an exception to Punnett squares in my biology

class

and it was me.

Teacher said that Mother’s lemon chiffon hair

and Father’s pearl body

couldn’t make me, thick chocolate mousse. I tried to explain that I wasn’t dessert

and Father wasn’t a jewel, just a ghost

or the white part of the blister on my big toe. She told me that albinos like him were half

parents, and half parents couldn’t make whole

children. Father

was half of a pigment,

half of a square, and whole was what I was, deep

mahogany

in this burning maple world. I didn’t want to tell the truth:

I got sunburned once

in Cancun.

That was when it started: the first time I had to face Teacher,

the first time I needed to say that this was my body,

it belongs here.

Maris Cohen is a senior English major and Women’s

Studies concentrator at Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Originally

from Baltimore, Maryland, Maris loves poetry, Ethiopian food, France, city life, her dear friends, and Virginia Woolf.

|