|

An American Map (Made in Michigan Writers) by Anne-Marie Oomen

Book Review by Tim Bazzett

Paperback: 205 pages

Publisher: Wayne State

University Press, 2010

Price: $18.95

ISBN-10: 0814334202

ISBN-13: 978-0814334201

Ever since reading with

great enjoyment and admiration Anne-Marie Oomen's first memoir, PULLING DOWN THE BARN, I have kept a sharp eye out for any

new prose pieces from her. Her second memoir, HOUSE OF FIELDS, was another small treasure. I came away from both of those

books with that feeling of having "gone to different schools together," probably because of a shared background of small towns,

farming country and a Catholic upbringing. And yet I have also always felt just a little bit intimidated by Oomen's writing,

which invariably shows a richly poetic, deeply feminine and a subtly nuanced sensibility and imagination which I despair of

ever completely understanding. I guess you could say she got a whole lot more out those "different schools" than I did. Or

maybe she's just smarter than I am. But I keep on trying to learn.

In any case, I was pleased

to learn of her latest offering, a book of essays called AN AMERICAN MAP. Glancing at the contents and the far-flung settings

for each piece, I think I almost hollered, "Hot dog!" Because I have always loved to travel through books. In fact I'm pretty

sure I enjoy book-travel a lot more than the real thing. It's so much more comfortable, ya know? The essays here were prompted

by Oomen's travels over the past several years, and she has certainly covered ground: from Maine and D.C. in the east to Washington

and California in the west, and as far south as Arizona and Puerto Rico with several stops in those middle places too, particularly

her beloved home state of Michigan.

Oomen admits early on

in the collection that at least some of these trips were spurred by a sense of restlessness and wintertime "cabin fever."

But she also speaks of a vague feeling of melancholia, sadness even, which she can't fully explain, but which had caused in

her a dismaying case of writer's block. That sadness, that "weight of the world" comes through in several of these pieces,

as she visits places as different as Mount Cardigan, New Hampshire, and Washington, D.C. in the essays, "Stone Wounds" and

"The Underpass."

Climbing that mountain

in New Hampshire, making her way up steep slopes of granite striated with shiny streaks of quartz, she remembers a story told

by Isaac, an old Native American she knew as a girl in her native Oceana County in Michigan. Isaac told her of a battle between

the People before time began in which all were killed, but the battle was so great that the warriors, when they died, "turned

to great dark stones, marked by lines of lighter horizontal color." Recalling this years later on a mountain side in New Hampshire,

she writes, "... with my hands I touch a wide line of running quartz ... the lines identified the stones as warriors."

In D.C. that same underlying

sadness rises again to the surface when she is suddenly "undone" at her first glimpse of the Vietnam Memorial Wall.

"All along that slick

and momentous length are names that, from a step back, become human texture in stone ... I come close, touch the dark surface

... run my fingers down a row."

Once again, lines in stone

identifying warriors, but this time from a not-so-distant past, and part of the source of that ineffable sadness and "weight

of the world" that sometimes threatens to overwhelm her.

But not all here is sadness

and woe. There were also "voila" moments of recognition which caused me to chuckle and add my own associations, as in her

essay about a trip to southeast Arizona called "Finding Cochise." I'm not sure how many people today, aside from American

history buffs and front-row kids like me, would immediately recognize the name Cochise, but it struck an immediate chord with

me, and for the same reason it did with Oomen, because apparently even some girls from that era loved the western movies that

proliferated in the fifties. She explains -

"As a child my male heroes

were Roy Rogers, because he sang 'Happy Trails,' the Lone Ranger and Tonto, for reasons I can't remember, and my secret hero,

Cochise, because I saw a movie in which he appeared in all the ways we would now perceive as politically incorrect ..."

This single line dropped

me back into the air-conditioned darkness of the Reed Theater nearly sixty years ago, munching my popcorn as I followed the

Technicolor saga of Indian agent Tom Jeffords (James Stewart) and his uneasy alliance with the war chief, Cochise, played

by dusky-skinned actor, Jeff Chandler, in the film, Broken Arrow. And then my mind skipped ahead to the later TV series of

the same name where Cochise was played by an actor of Syrian heritage, Michael Ansara. And speaking of Tonto, Anne-Marie,

Jay Silverheels had a featured role in both Broken Arrow and its film sequel, Battle at Apache Pass. And while we're talking

cowboys and Indians, if you and David had continued just a few more miles NE from Cochise, you would have come to Willcox,

the home of "the last of the silver-screen cowboys," Rex Allen, where you could have visited The Rex Allen Museum.

Okay, I know I'm pushing

the parameters of what constitutes a review here, but I had my raggedy old Rand McNally out, as I always do when reading about

far-away places, and there was Willcox staring me in the face. How could I not mention this? There might be some other old

buckaroos and cowgirls out there reading this.

And just to keep the record

straight, I DO recognize that "Finding Cochise" is about more serious things than cowboys and Indians. I will, however, let

other readers discover that for themselves. But while I'm at it, here's one other mostly irrelevant comment about another

essay, "Squall," which might serve to embarrass Anne-Marie at least a little. In this piece about fly-fishing, Oomen is visiting

her two adult sisters in Colorado, and, in a most uncharacteristic manner, she manages to use that four-letter word for manure

at least four times in less than a dozen pages. It must have been something about being with family again that took her back

to her farming roots. Her always practical mother, she tells us in a later piece, used to tell her children matter of factly

that the smell of manure shouldn't ever bother anyone; that it simply "meant everything was working."

An especially beautiful

piece called "The River Inside (A Prose Poem)," with its ruminative stroll through an old church graveyard along the Huzzah

River in Missouri, struck sparks of memory within me of a classic prose poem I studied eons ago in college, Edgar Lee Masters'

SPOON RIVER ANTHOLOGY.

Perhaps my favorite piece

of the whole collection is the one called "Finding (My) America," in which Oomen travels to four different small-town libraries

in northern Michigan as part of a book tour. She identifies herself as "a nerd for valuing books, for reading them, for loving

to hold them, smell them and turn their pages, for revering the places they take me, as well as the places they are housed."

Me too, Anne-Marie - book

nerd extraordinaire.

It occurred to me as I

was holding this particular book, smelling the ink and the glue, turning the pages and examining the cover, that the author's

initials form an interesting acronymn - AMO. In Latin, "amo" means "I love." And, if you look closely in this collection of

essays, you will find, tucked here and there, a continuing and intimate love letter to Oomen's husband of many years. In the

end, for me AN AMERICAN MAP is a book that is dense with associations and filled with impeccably beautiful prose. In case

you haven't guessed it yet, "I love" this book.

Lessons from the

Borderlands by Bette Lynch Husted

Book Review by Tim Bazzett

Paperback: 174 pages

Publisher: Plain View

Press, 2012

Price: $18.95

ISBN-10: 1935514857

ISBN-13: 978-1935514855

I heard about LESSONS

FROM THE BORDERLANDS from writer Molly Gloss (The Hearts of Horses), who praised the book highly and said it deserved a wide

readership. She was right. Husted's stories of her poverty-stricken childhood in Idaho and subsequent struggles to improve

her own life situation are beautifully written, and I mean writing that pulls you into her life and makes you care. I could

relate to Husted's continued attempts to "fit in" even after she'd graduated from college and, later, grad school. She always

felt like the poor cousin, unworthy somehow to partake of a better life. In that respect, her essays are about class, about

the unofficial and not often discussed "caste system" in America. She illustrates this with examples of her discomfort - and

sometimes even mistreatment - in restaurants, stores and other public settings. With all the recent talk of the shrinking,

or even disappearing, middle class in America, Husted's own stories ring true. I thought too of Paul Fussell's book, Class:

A Guide Through the American Status System. I don't know if Husted has ever read that book, but here is her own homespun version,

her personal experiences, as well as those of many of her students in public schools and community colleges over the years,

which all serve to show the painful struggles for upward social mobility which continue to this day.

But LESSONS is also a

moving memoir of family. And Lynch-Husted's family had as much dysfunction and as many family skeletons as any. But I was

particularly touched by her reminiscences of her mother, "who at 88 is still my best teacher." My own mother is now 95, and

like Bette's, has always been my best teacher. And like Bette's mother, mine has always loved to read. My mother's sight has

begun to fail, but she still reads, more slowly and with some difficulty. And, like Bette, I always ask her, "What are you

reading?" Mom is in a nursing home now, which is always hard. I worry about her happiness, her quality of life. And so I understand

the importance of the reassurance Bette got from her own mother, who said, about a book she was reading: "Don't worry - I'm

okay ... I'm just savoring this one. I don't want it to end."

That's how I felt about

this special book, LESSONS FROM THE BORDERLANDS. I'll say it again. This is simply beautiful writing. Husted's mom must be

proud. I'm passing it along to my own mother soon, to read - and savor. Thank you, Bette, for telling your story.

Turning

Pages: A Memoir of Books and Libraries and Loss by Daniel Dyer

Book

Review by Tim Bazzett

File Size: 532 KB

Print Length: 298 pages

Sold by: Amazon Digital

Services, Inc.

Price: $4.99

ASIN: B007L2LBU8

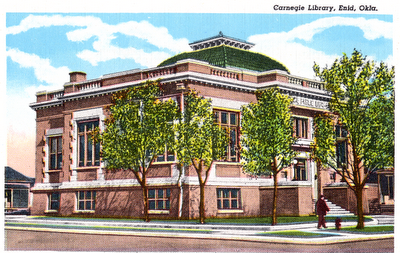

I found Daniel Dyer's memoir, TURNING PAGES,

to be totally engrossing and utterly delightful, due mostly, I think, to the absolute honesty of his memories of growing up

in Enid, Oklahoma and Hiram, Ohio. The book also chronicles the life of philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, a carefully researched

and fascinating mini-biography which alternates chapters with Dyer's own story which featured a nearly life-long reverence

for libraries. So there is much here about the Carnegie library in Enid that was built nearly a hundred years ago but is now

gone, a victim of neglect and 'progress.'

Dyer covers a lot of ground in TURNING PAGES

- racism in the south during his 50s childhood, favorite books, teachers and librarians, sexual awakening, family relationships

(in an ultra-bookish family), teenage rebellion and more. But what drew me to the book in the first place was the possibility

that here would be a book about books, and I was not disappointed in that regard. Probably because Dyer and I are about the

same age, we seem to have read many of the same books, from childhood all the way up into adulthood. He too remembers those

orange-covered biographies of famous Americans written for schoolchildren. I remember reading of Buffalo Bill, Kit Carson,

and George Washington Carver, and so does Dyer, who became fascinated with not just Carver, but with his biographer, Bontemps.

Dyer talks too of Dr. Seuss, John R. Tunis and the Hardy Boys and (gulp) yes, even Nancy Drew. He also knows his classics,

and how he was introduced to them through Classics Illustrated comic books. He mentions too some books I missed out on. One,

Daniel Nathan's THE GOLDEN SUMMER, sounds particularly enticing, even if it is a boy's book.

Both Dyer's parents were educators and avid

readers. The Dyers were in fact a family of readers, and there are book references galore here, something I absolutely loved.

The library of my own childhood was not a

Carnegie library, but it was still an enchanted place for me, and I probably visited there at least twice a week throughout

my school years. Like Enid's libary, ours was located in the center of town, upstairs over City Hall, in fact. You probably

can't be any closer to the heart of a community than that. I remember reading practically everything in the 'children's section,'

especially all the animal stories by authors like Kielgaard, London, O'Brien, Curwood, Terhune, Farley and others. Dyer mentions

some of these too, if I remember correctly. Dyer also talks about his early-formed habit, or perhaps compulsion would be a

better word, of trying to read every work of favorite authors, a practice he learned from a favorite teacher and has continued

to follow ever since. While I admire him for managing to read all of Trollope, I don't think I'll ever match that kind of

obsessive reading behavior. (I have, however, read most of the works of a distant relative of that writer, Joanna Trollope,

which I have enjoyed tremendously.)

So okay, this is a book about books, about

libraries, and about Daniel Dyer's life. It also seemed to be a lot about my own life. Maybe that's the mark of a really well-written

memoir, one that makes you remember more about your own life. As a memoirist and a booklover, I loved this book. Er, e-book,

that is. (Which is my one and only beef about TURNING PAGES. I wish that, kinda like Pinocchio, it were a 'real live book'

and not just pixels and electronic stuff, or whatever an e-book is.) But here's my bottom line: if you love books, you'll

love TURNING PAGES.

|