|

|

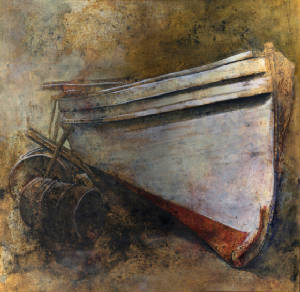

| Searching for Icarus, painting by Margo McCafferty |

I. Free Falling

by Maggie Jackson

Hadley sits next to me in the car that is not yet hers, her bare feet propped on

the dash, the purple polish on her toes chipped—neglected from long hours encased in boots, escaping even my sister’s

meticulous attention. We are both wearing sundresses. Our bare legs stick to the grey leather, making moist snapping sounds

every time we move them, the pale skin we share dotted here and there with freckles, but otherwise as white as February, even

in the gentle warmth of late April.

In Montana, we do not have the luxury of waiting for the perfect day for spring to

begin. The season is so short here; it sometimes seems like a figment of the imagination, a daydream half-remembered on a

Sunday afternoon between the abrupt departure of winter’s final storm and the alfalfa-scented arrival of high summer.

It is a constant guessing-game we play, not knowing which day might end in dense, wet snow, which in impromptu picnics in

Lion’s Park at sunset. We dress for the weather we want. We do not let our uncertainty bully us back into jeans and

sweatshirts.

The windows are down—I can smell the dry, dusty aroma of warm asphalt I’ll

always associate with summer in Great Falls—and I’m driving too fast. Hadley’s eyes are fixed somewhere

out toward the mountains, her thin freckled arms crossed over her chest, her hair whipping in long, taffy thick strands around

her head.

I’ll learn a word in college for the color of her hair—my art history

professor will call it Titian, after the Venetian artist who had a thing for redheads. I’ll remember a family road trip

to Seattle, my mother reading Nancy Drew out-loud and mocking the archaic language that describes the heroine thus. I’ll

remember gazing at the back of my sister’s lustrous hair from my seat behind her. I’ll remember my sigh of envy.

“You’re going too fast, Maggie.”

Her voice is sanctimonious, accusatory. It’s the voice of one for whom driver’s

ed is in the offing, so close to the freedom that driving implies and yet still only able to correct from the passenger’s

seat. She looks at me levelly, waiting for my retort.

“There’s no one around,” I say, and stamp the gas for just a second,

being contrary for the sake of it.

She rolls her eyes in that perfect eighth grade gesture, the pfffsheeah of her scoff

a pitch-perfect replication of every scornful teenager in the history of puberty. I throw her sound effect right back, the

mocking note in my voice as old as sisterhood itself.

We lapse back into silence, as we turn right onto the back road that leads to Hospice.

It’s the most interaction we’ve really had for days. We usually stay out of each other’s way, orbits rarely

crossing except for when they intersect nightly at dinner, when all five of us sit down to a meal in a ritual that, when I’ve

seen a little more of the world, will seem impossibly ideal—a remnant from a more innocent, less frenetic age.

But the last weeks have taken on a different cadence. With Mom spending most of her

time either at school or at Hospice with Grandma, Hadley and I have been in each other’s company even less than usual.

The five years that divide us, with her longing to experience the halls of Great Falls High School just as I am desperate

to get the hell away from them, stretch like a chasm between us. Silence is usually easiest.

Neither of us, I can tell, is really looking forward to the impending visit to Hospice.

When you’re young, a place built specifically for the purpose of facilitating death seems incomprehensible. Sacrilegious.

And seeing our mother sit beside her mother’s bedside day after day brings the uncomfortable cyclical nature of death

a little too close for comfort. It’s not the beautiful, triumphant circle of life we sing about on long car rides. It’s

something much closer, less immediately moving. And neither of us wants to think too much about it.

I switch on the radio to fill the silence. Steve Keller gives the hourly weather

report—clear skies and mild tonight with a chance of showers tomorrow—and an advertisement for Kleen King tells

us to “give those carpets the royal treatment”. Neither Hadley nor I am really listening. We’ve heard 97.9:

The River too often to really pay attention to the ads anymore.

And then the song starts. The five chords strummed out, sustained in such a way that

they immediately loosen the tension in my shoulders, their repetition reverberating across my skin, warming it with the promise

of languid days spent sprawled in the grass, or running barefoot through puddles in a summer thunderstorm. Both Hadley’s

hand and mine reach for the volume knob at the same moment. She gets there first, and cranks the song so Tom Petty’s

voice fills the car, spilling out through the open windows into the world beyond.

She’s a good girl—loves her mama,

loves Jesus, and America too.

She’s a good girl—crazy ‘bout Elvis.

Loves horses, and her boyfriend too.

Our parents have always prided themselves on raising us with good musical tastes.

We’ve been brought up listening to everything from the Beatles to The Four Seasons to James Taylor to Les Miserables,

and so my siblings and I share an almost preternatural affinity for music, and especially for remembering lyrics.

Hadley and I are both mezzo-sopranos, our voices floating along together, an octave

higher than Tom’s as we sing in full voice, the words as familiar to us as the hospital buildings passing by on our

left, the Hospice center growing ever-closer up ahead. Hadley is moving unconsciously to the beat, her head following the

syncopated rhythms of the drums, her eyes closed as she belts the familiar verse, one that’s been a part of our world

since before either of us can remember.

It’s a long way, living in Reseda—

there’s a freeway running through the yard.

And I’m a bad boy, ‘cause I don’t

even miss her—

I’m a bad boy for breaking her heart.

There are certain musical sequences that will always produce the same effect in me,

no matter how old I get, no matter where life takes me. The chorus that we sing with wild, impetuous abandon is one of these.

There’s a bubble of inexplicable joy rising up in my chest, my body reacting to the music like a physical stimulus,

a smile breaking over my features, tears pricking right behind my eyes. It is all I can do not to close my eyes, to let myself

sink fully into the sensation of the music. As it is, my speed has crept up again, seduced by the tempo of the song. Hadley

is too lost in the melody to comment.

We pull into the parking lot at the back of the Hospice building. It’s a low,

pleasant, peaceful place with a garden where a fountain is playing. It’s the kind of place built for low voices and

quiet murmurs. It is not the place for pounding bass, or the half-shouted singing of two teenage girls and one ‘80s

alt-rocker. But we do not turn down the music. We couldn’t even if we wanted to.

Instead, we sit, the car still running, both of us moving in time to the familiar

chords. There’s no silence between us anymore, but instead the ecstatic, joyful release that comes with a familiar,

beloved song. We break off into long-practiced harmonies at the end, her voice finding the lower, mine the higher notes. We’re

lost in our own experiences of the music. Alone, and yet hyper-aware of the other’s presence, her place in this moment

of release from the painful weeks of waiting for the inevitable to finally happen.

As the music winds down, the final moment of respite is marred by the zany sound

effects that are the hallmark of every small-town radio station. We’ve got no time to savor before Ricky Martin begins

to croon, erasing the echoes of the final few notes of our song beneath sultry Latin beats.

I turn off the car, and the silence resumes. I can see the window of Grandma’s

room illuminated with the soft glow of a bedside lamp. Mom will be sitting in the big char, correcting tests or writing lesson

plans while Grandma breathes raggedly in her hospital bed. We don’t know how much longer this will be the way of things.

I open my door and get out of the car, my bare legs peeling off the seat with an

unpleasant sucking noise. Hadley’s legs make the same sound when she gets out. We look at each other over the top of

the car, lost for a moment in between the euphoric escape of the music and the sickening reality in which bare legs get stuck

to leather seats. We both begin to laugh at the same time.

We walk around to the front of the car, striding side by side up the sidewalk, the

silence different now than it was ten minutes ago. Hadley smiles briefly at me as she opens the door to the room with the

garden view, humming under her breath:

I wanna glide down over Mulholland,

I wanna write her name in the sky.

Gonna free-fall out into nothing—

I wanna leave this world for awhile.

I take up the chorus like a talisman as I follow her inside.

Maggie Jackson teaches 10th Grade Language Arts at Sierra High School in Colorado Springs, Colorado,

through the Teach For America program. She is an alumna of Kalamazoo College, where she graduated Magna Cum Laude with a degree

in English Literature and Creative Writing in 2011. She has previously been published in Kalamazoo College's The Cauldron, as well as Lyric. She is currently refining her first

full collection of poetry, Lilacs on Copper Street, for publication.

Wonderful Seeds

by Amy Newday

Convince me that you have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders. ~ Henry D. Thoreau

January is the month of magic-peddlers,

glossy catalogs promising all manner of visual and culinary delight in the form of small, dry seeds. A quick glance through

their bright pages offers a visual taste of what we’ve lost by consolidating our food production systems into large

corporate farms which grow massive quantities of single crops for shipment around the world. Sure, we can eat pineapples year-round

in Michigan, but where on our supermarket shelves are the plum purple radishes, the golden beets? Where are the plump, white,

lavender-blushed Rosa Bianca eggplants? What happened to Jimmy Nardello’s Sweet Italian Frying Pepper, the seeds of

which Jimmy’s mother carried with her when she immigrated to the United States in 1887? What about sweet, tart, Green

Zebra tomatoes? Anyone remember Patty Pan squash?

I’m enormously grateful

to the plant breeders and organizations actively working to preserve the diversity of our agricultural seed stock. I’ve

spent the past month scouring their catalogs as I created this year’s production plan for our small vegetable farm.

Because we are primarily supported by a group of CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) customers who invest in our farm each

year in exchange for weekly shares of produce throughout the growing season, it’s important that we plant a wide range

of crops for our customers to enjoy and that we schedule our plantings so that we can harvest a nice assortment of vegetables

each week during our CSA season.

In selecting our season’s

crops, I looked for varieties with delicious flavors, disease-resistance, and hardiness under variable growing conditions.

Because our farm is small and our customers local, we’re able to offer varieties of produce that larger farms can’t.

Farms that rely on mechanical harvesting or that ship their produce cross-country must choose crops that will hold up to rough

handling and an extended stay on a supermarket shelf. Flavor is a distant second (or third) consideration. Since we harvest

by hand and have our produce to our customers within a few days, we have the luxury of selecting vegetables primarily for

their taste. But because we use organic growing methods, we also look for crop varieties that have natural genetic resistance

to common pests and diseases. And because Michigan’s weather can vary unpredictably from season to season, we want varieties

that can flourish under a range of growing conditions.

I also consider broader ethical,

economic and environmental issues in deciding which types of seeds to purchase and which companies to buy them from. If you’ve

ever spent a chilly winter evening flipping through a seed catalog, you might have noticed that some varietal names are followed

by the abbreviation “F1.” This stands for “filial 1,” but in more common language these plants are

known as hybrids. Their seeds have been created by cross-pollinating two plant strains to produce offspring that have improved

qualities over each of their parents. However, because of the wonderfully complicated genetic dance that creates and sustains

life as we know it, the children of these offspring (or F2 generations) may not retain these desirable traits. It’s

kind of like when your Cousin Millie ends up with your grandfather’s green eyes and red hair when your parents and all

of your aunts and uncles are brown-eyed brunettes. Because planting seed saved from hybrid varieties can have unpredictable

results, farmers usually re-purchase hybrid seeds each season rather than trying to breed their own seed stock from these

plants.

Some folks in the sustainable

foods movement are concerned about the proliferation of hybrid varieties in our modern agricultural system. Rightly so, I

think. Though cross-pollination is a natural process which anyone could facilitate given the right knowledge and resources,

problems develop when corporations claim exclusive rights to parental strains, forcing farmers to purchase seeds year after

year rather than having the option of breeding their own plants. This makes our global food supply more vulnerable by limiting

the overall genetic diversity of our collective seed stock. I don’t believe, however, that the misuse of hybrid technologies

by a few corporations justifies the abandonment of this valuable and time-tested plant-breeding technique. When open-pollinated

(non-hybrid) varieties of similar qualities are available, we choose them. And when superior hybrids are offered, we’re

happy to purchase them from reputable companies.

There are certain types of seed

that we refuse to plant, however. Unlike cross-pollination, genetic modification is not a natural process. To create genetically

modified crops, scientists physically alter DNA, the genetic blueprint on which life is built and which drives both its form

and functioning. An analogy—when I was a young child, before I had any notion of sexual reproduction, I asked my mother

what would happen if my brother married our dog. What would their kids look like, I wanted to know. People and dogs can’t

have kids together, my mother replied. But what if they could? I insisted, undeterred by any concept of biological impossibility.

It can’t happen, my mother reiterated, people and dogs can’t have children.

But with genetic modification,

they now kind of can. In the chapels of their laboratories, scientists have married such diverse species as corn plants and

soil bacteria, intermingling their genes in a single strand of DNA. What’s the problem? Part of the problem is that

we don’t entirely know what problems these new genetic combinations may cause in the ecosystems outside of laboratories.

But we’re creating some problems with these genetically modified organisms (GMOs) that are very predictable. In the

case of the corn and bacteria, genes from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) which produce a protein toxic to

caterpillars are inserted into the genome of corn plants. If you’ve ever pulled back the husk on an ear of sweet corn

to find a writhing grey worm and a trail of caterpillar poop across the sweet, ripe kernels, you can imagine why farmers might

want to plant a crop with such a genetic combination, since that little worm’s first bite of succulent corn would be

its last.

Here’s the problem, though.

Life adapts and species change in order to survive. We know this—it’s why doctors are cautioned not to over-prescribe

antibiotics, so that they don’t facilitate the development of antibiotic-resistant strains of diseases. When you take

an antibiotic, or when a farmer sprays pesticides on her crops, the poison usually doesn’t eradicate every single organism

that it targets. A few organisms survive the poison and reproduce, passing on their genes to the next generation. The next

time the farmer sprays the pesticide, the strongest of these offspring are the ones that survive to reproduce. Eventually,

if this continues, the majority of the pest population may end up being genetically resistant to the poison.

So when a toxin such as Bt is

constantly present in the environment inside a widely-planted host crop such as corn, it creates a literal breeding ground

for Bt-resistant strains of caterpillars. This is especially unfortunate since Bt is actually a great tool for organic farmers.

A naturally-occurring bacteria non-toxic to animals (including humans) it’s one of the few organic substances available

to combat caterpillars such as cabbage loopers and tomato hornworms, in addition to the earworms and borers which can plague

corn crops. The fear that we share with the organic community is that Bt may quickly lose its effectiveness due to overuse

in GMOs. This might mean that we’d have to make the difficult choice to either use substances that are more dangerous

to humans and/or more ecologically harmful in order to protect our future crops or to not grow crops such as sweet corn at

all.

We’ve ordered our seed from

companies which have signed the Safe Seed Pledge, affirming their refusal to sell GMOs. It begins: “Agriculture and

seeds provide the basis upon which our lives depend. We must protect this foundation as a safe and genetically stable source

for future generations.” As I slice open the padded envelopes and boxes of seeds now arriving in the daily mail, I turn

these words over in my mind. The round, red-brown pellets of turnips, the pointed flakes of lettuce, and the tan discs of

tomatoes and peppers are small, unspectacular. But they are our foundation; every sprout, every leaf, every succulent vegetable

begins inside these seeds. We expect wonders.

Amy Newday is the co-owner of Harvest of Joy Farm, LLC and a fourth-generation farmer on her family’s land. She holds an undergraduate degree in biology through Adrian College

and an MFA in poetry through Western Michigan University. Her poems have appeared in publications such as Poetry East,

Rhino, Notre Dame Review, Calyx, and Flyway, as well as in The Smoking Poet. She lives in Shelbyville,

Michigan, and currently divides her time between farming and directing the writing center at Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo,

Michigan.

|