|

|

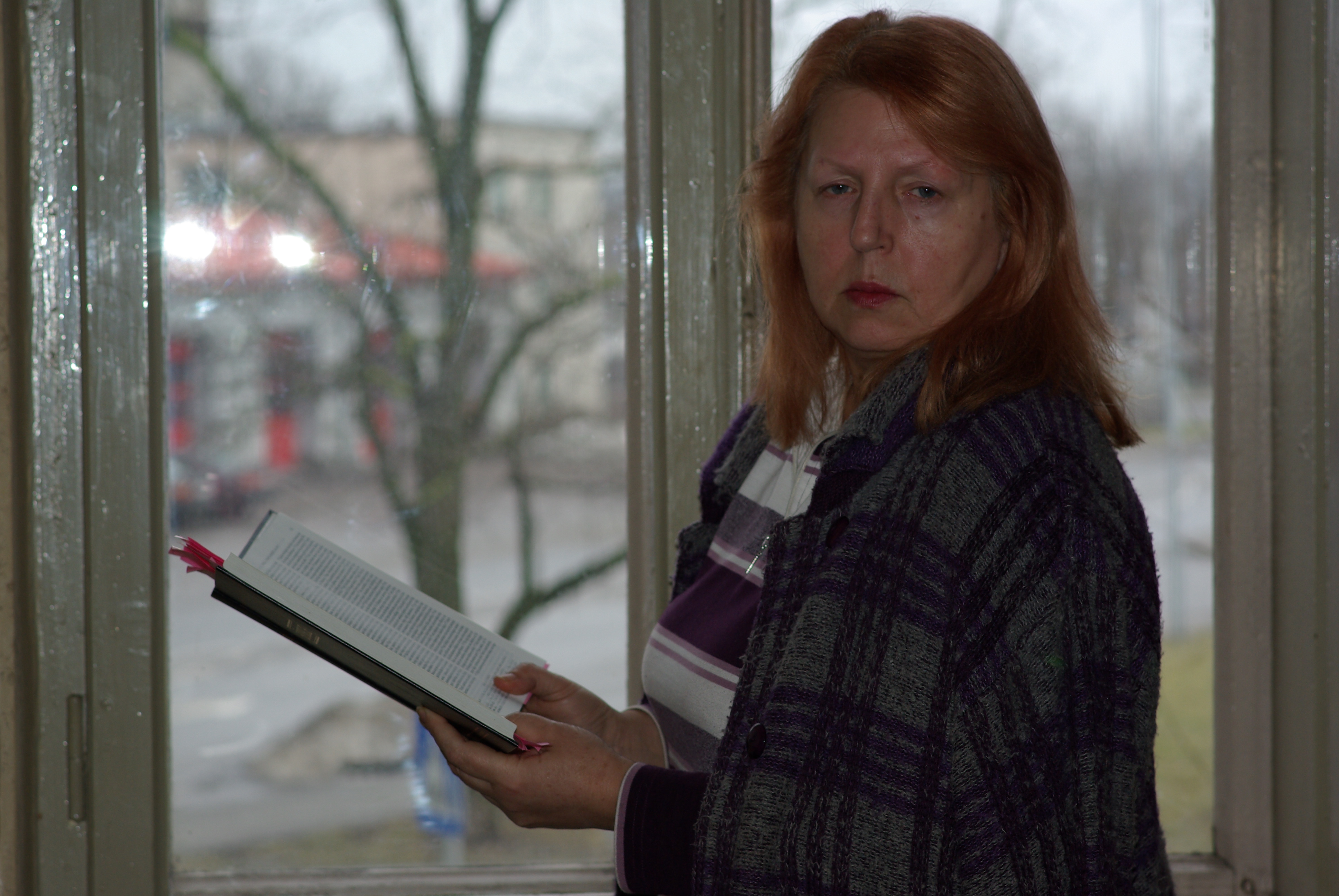

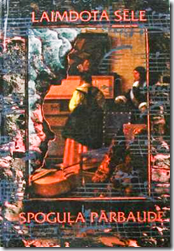

| Latvian Author Laimdota Sele |

Zinta for The Smoking Poet: Welcome, Laimdota! It’s a special thrill for me

to interview you—my Ventspils sister! Special, too, because this gives me an opportunity to let our readers know something

more about Latvia. Let’s begin by having you tell our readers something

about yourself. Where you were born, and if you could describe the world, your world,

around you at that time and as you grew up in Latvia.

Sveika, Laimdota! Tik ļoti priecājos

tevi intervēt, savu Ventspils māsiņu! Priecājos arī par šo izdevību iepazīstināt

TSP lasītājus ar Latviju. Iesāksim ar īsu biogrāfiju. Kur esi dzimusi, kādā pasaulē

iedzimi, ja būtu iespējams to aprakstīt tavos pirmajos gados.

Laimdota Sēle: Paldies, mīļo māsiņ, par iespēju šādā veidā uzrunāt

lielās un plašās US lasītāju. Esmu dzimusi, kā Tu jau zini, krievu okupētajā Latvijā

1951. gadā, tātad var teikt, ka manas dzimšanas laikā Latvija bija okupēta jau otro reizi (1940 un

1945). Tie bija bargie Staļina laiki, ko vēlāk mani vecāki un vecvecāki atcerējās ar šausmām

un bailēm. Mans tēvs, bijušais Latvijas nacionālais karavīrs, kurš „Kurzemes cietoksnī” cīnījās pret okupantiem līdz pēdējam, bija spiests mainīt uzvārdu, un mana

māte pašaizliedzīgi palīdzēja viņam vispirms slēpties, pēc tam uzsākt legālu

dzīvi. Viņam nācās strādāt primitīvu darbu, lai varas iestādes nepievērstu viņam

uzmanību, tāpēc mana bērnība pagāja diezgan lielā trūkumā. Taču man nebija

iespēju salīdzināt, jo citādus dzīves apstākļus nepazinu. Zināju, ka Amerikā

dzīvo mana vecmāmiņa un vectēvs (tēva vecāki), bet par to runāt nebija vēlams. Diemžēl

šos savus senčus es tā arī nekad neredzēju. Tomēr savu bērnību es nesauktu par nelaimīgu,

pirmkārt, tāpēc, kā jau minēju, man nebija iespēju salīdzināt, otrkārt, dzīvoju

savā pasaulē – mūsu vecajā mājā un dārzā, ko mums, par brīnumu, neatņēma,

ļoti daudz lasīju un... fantazēju.

Thank you, my dear sister, for

this opportunity to address the many readers of United States. I was born, as you know, during the years of Latvia’s

Russian occupation in 1951, so you could say that during the time of my birth, Latvia had been occupied for the second time

(1940 and 1945). Those were the brutal Stalin years that later my parents and grandparents recalled with horror and fear.

My father, who fought in the Latvian national army in the battle at the Kurzeme fortress against the occupants until the very

last, was forced to change his last name, and my self-sacrificing mother at first helped him to go into hiding, and after

that to resume a more or less legal life. He was forced to work in meaningless, low-paying jobs so that the occupying forces

would take no notice of him, and so my childhood passed in poverty. But I had

no standard of comparison, because I knew no other life. I knew that my paternal grandmother and grandfather lived in America,

but it was understood that one did not talk about such things. Unfortunately, I never had the opportunity to meet them. And

still, I would not call my childhood unhappy—first, because as I mentioned I had no point of comparison, and second,

because I lived in my own world—in my parents’ old house and yard, which, miracle that it was, was not taken away

from us, and I read a great deal … and I fantasized.

Zinta: How did you become a writer? How has your career as a journalist, as a writer, molded you and your life?

Kā kļuvi par rakstnieci? Kā

tava karjera kā žurnāliste, kā rakstniece, tevi un tavu dzīvi veidojusi?

Laimdota: Kopš 11–12

gadu vecuma mani ļoti interesēja vēsture, un to es izvēlējos par savu nākamo profesiju. Mācījos

Latvijas Universitātes Vēstures fakultātē neklātienē, taču augstskolu nepabeidzu... Nepabeidzu

tāpēc, ka nevarēju sevi piespiest apgūt (iekalt!) tik absurdus mācību priekšmetus kā

„marksisma ļeņinisma filosofija”, „zinātniskais komunisms”, „sociālisma

politekonomija” un tamlīdzīgus, bet tieši šajos priekšmetos bija jākārto valsts eksāmeni.

Nekad neesmu spējusi sevi piespiest melot un izlikties; kad vidusskolas laikā man LIKA iestāties komjaunatnē

(komunistu organizācija jaunatnei) es drīzāk biju gatava, lai mani izmet no skolas, nekā šādā

veidā pārdot savu dvēseli un apgānīt savu vecāku un vecvecāku ideālus. Mani sauca

par traku, tāpat arī manu aiziešanu no augstskolas priekšpēdējā kursa – par neprātu,

taču tāda spītniece nu reiz biju, un nekad neesmu to nožēlojusi. Strādāju dažādus

darbus – kādus gadus muzejā, tad šur tur par lietvedi, sekretāri, arī par mākslinieci

J pilsētas lielākajā kinoteātrī, bet 1985.

gadā man gluži nejauši piedāvāja darbu laikraksta redakcijā par žurnālisti. Tā

kā tad jau bija sākušās lielās pārmaiņas bijušajā PSRS („perestroika”

– pārbūve), es tur varēju strādāt, arī nebūdama komjaunatnē vai kompartijā,

rakstīju visvairāk par kultūras jautājumiem, pilsētas vēsturi, bet, sākoties Atmodai (1988)

– arī par politiskiem jautājumiem un pārmaiņām. Taču literatūrā pirmie soļi

bija jau agrāk, visvairāk dzeja, pirmās publikācijas bija 70. gadu vidū. Astoņdesmito gadu sākumā

pārdzīvoju ļoti spēcīgu emocionālo pacēlumu personiskajā dzīvē, kas mani

mudināja rakstīt daudz aktīvāk; šajā laikā sacerēju 2 lugas, iesāku savu pirmo

romānu „Spoguļa pārbaude”, un no šajā laikā uzrakstītajiem dzejoļiem iznāca

mana pirmā dzejas grāmata „Izšķilt mīlestību” (1989). Tolaik darbojos arī Ventspils

Vides aizsardzības klubā, ko varētu nosaukt par vienu no pirmajām pretpadomju organizācijām

Latvijā un kas, vēlāk iekļaujoties Latvijas Tautas frontē, palīdzēja novest Atmodas procesu

līdz valsts neatkarības atgūšanai. Tas atkal bija jauns stimuls rakstīt, rakstīt, celt gaismā

visas tās lietas, ko padomju okupācijas laikā vajadzēja slēpt un klusēt – Latvijas ĪSTO

vēsturi, brīvības cīņas 1918–1919, pirmās brīvvalsts laiku, Baigo gadu, dubulto –

krievu un vācu okupāciju utt. Kļuva pieejami daudzi avoti, kādu agrāk nebija. 1991. gada janvārī

arī es biju Rīgas barikāžu aizstāvju rindās; tur pārdzīvotais bija neaizmirstams...

Tūlīt pēc tam, kad 1994. gadā iznāca „Spoguļa pārbaude”, sāku strādāt

pie romāna „Mūsu mīlestības gadsimts”, kur barikāžu laika ainas mijās ar Latvijas

20. gs. svarīgāko notikumu epizodēm. Tikai pēc šī romāna iznākšanas sāku

sevi uzskatīt par rakstnieci...

Since I was 11 or 12 years old,

I have been very interested in history, and I wished to pursue it as my profession. I studied history at the University of

Latvia, but I did not graduate … I did not graduate because I was completely incapable of completing such absurd courses

such as Marxist Leninist Philosophy, Scientific Communism, the Political Economics of Socialism, and so on, but these were

the subjects in which a history major had to pass exams. I have never been able to force myself to lie and pretend; when during

high school I was FORCED to join the communist youth organization, I was ready to let myself be suspended from school rather

than to sell my soul and taint the ideals of my parents and grandparents. I was called crazy, as was my leaving the university

just prior to completing my degree, but I was stubborn and have never regretted it. I worked in all kinds of jobs—some

years in a museum, here and there as an accountant, a secretary, even as an actress in our city’s largest movie theatre,

but in 1985 I was coincidentally offered a position as a journalist at our city newspaper. Since the political movement of

“perestroika” (revival) had begun, I was allowed to work there without being a member of the communist party,

and I wrote most about cultural topics, city history, but, once the 1988 national rebirth movement began, even about politics

and political changes. My literary endeavors began earlier, however, mostly in poetry, with my first publication in the mid

‘70s. In the beginning of the ‘80s, I experienced a very powerful emotional upheaval, and that drove me to wrote

more actively; during this time, I wrote two plays, started my first novel, Spogula Parbaude (The Test of Mirrors), and from

the poetry written in this time, my first poetry collection, Izskilt Milestibu (1989), or The Birth of Love. At that time,

I also took part in greater Ventspils protection league, which you could call one of the original anti-Soviet organizations

in Latvia, and which, later joining the National Latvian Front, helped to bring the process of renewal to the conclusion of

regaining our independence. Once again, I was inspired to write, write, bring

into the light all that had been hidden and silenced during the Soviet years—the true history of Latvia, our freedom

fight of 1918-1919, our first independence, the year of horror (1940-1941), the dual occupation of Nazi Germany and Soviet

Russia, and so on. I could access materials that I could not access before. In January 1991, I also stood on the barricades

in Riga (when the Soviet occupation was overthrown), and what I experienced there was unforgettable… Immediately after that, when The Test of Mirrors was published, I started work on my novel, Musu Milestibas

Gadsimts (The Century of Our Love), where scenes from this time on the Riga barricades intertwined with scenes from the 20th

century in Latvia and our most historic events. Only after this novel was published did I begin to think of myself as a writer

…

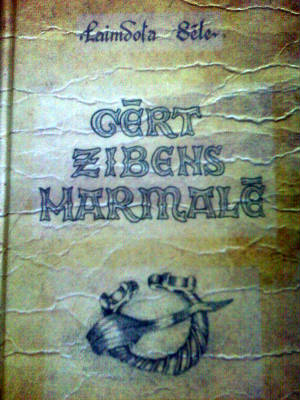

Zinta: In much of your work, and very much so in this newest novel, Cērt Zibens

Marmalē (Lightning Strikes The Sea), you delve into Latvian history, specifically into the history of Ventspils.

Why is it important to understand one’s history and the history of place? What have you learned about your home—and

yourself—through your historic research?

Daudzos tavos darbos, ieskaitot Cērt Zibens

Marmalē, tu raksti par vēsturi, specifiski Ventspils vēsturi. Kādēļ ir svarīgi pazīt

vēsturi, gan savu gan vietas vēsturi? Ko esi ieguvusi no šīs vēstures izpētes?

Laimdota: Kā jau teicu, vēsture ir mana lielākā interese, pat kaislība (neraugoties uz to, CIK

MAZ no šī priekšmeta izdevās apgūt padomju laika augstskolā); absolūti lielāko daļu

savu zināšanu esmu apguvusi pati, nemitīgi lasot, meklējot, mācoties. Ventspils ir mana pilsēta,

mana mīlestības zeme, tādēļ mani interesē ikviens tās vēstures mirklis – tāpat

kā mēs gribam uzzināt pēc iespējas vairāk par cilvēku, kuru mīlam no sirds. Diemžēl

daudz kas no manas pilsētas pagātnes ir zudis un nogrimis vēstures dziļākajās dzīlēs

– šeit pāri gājis tik daudz karu, tik daudz iekarotāju, kas ir laupījuši un dedzinājuši,

postījuši tīrā prieka pēc... tādēļ man šķiet tik svarīgi atjaunot kādu

no zudušajām lappusēm! Tas nav, kā saka, grābts no gaisa vai izperēts fantāzijā, bet

pamatots saglabājušajos avotos, arheoloģiskajos izrakumos (pati esmu piedalījusies) un meklēts analoģijās

ar līdzīgu (vietā un laikā) pilsētu rašanos. Zināt savas pilsētas un zemes vēsturi

manuprāt ir tikpat svarīgi kā zināt savu paša dzīves gājumu, taču šo domu var

paplašināt – jo vairāk zināms par pasaules vēsturi, jo vairāk uzzini par cilvēkiem,

kas tajā dzīvo. Vispār ir grūti nodalīt vēsturi un tagadni, jo viena izriet no otras.

As I said, history

is my greatest interest, even passion (in spite of how little I could learn about this topic during my Soviet school years);

in great part I gained my knowledge through independent study, constantly reading, seeking, researching. Ventspils is my city,

the city of my love, so every moment of her history interests me—just as we wish to know every detail about the one

we love with all our hearts. Alas, much of city’s history is lost and sunk into the deepest cracks of time—this

place has been ravaged by so many wars, so many armies, who have destroyed and burned, devastated for the sheer pleasure of

destruction … this is why it is so important to me to resurrect something of our lost pages! This isn’t, as one

might say, pulled out of thin air or imagined in fantasy, but carefully researched in archives, in archaeological finds (I

have participated in some of these digs) and compared to similar analogs (in place and time) in the birth of other cities.

To know the history of one’s city and country, in my opinion is as crucial as knowing one’s personal history,

and we can expand on this line of thought—the more we know about the world’s history, the more we understand the

people who live in it. It is difficult to separate history and the present, because one is born from the other.

Zinta: Tell us about your research. This novel has within it strikingly accurate representation of a time period, including

language, social interactions, customs, clothing and jewelry. How did you research for this novel and how much time did you

take on research before you began writing? Did you find anything that surprised you? Did you take artistic license in some

areas?

Pastāsti par saviem pētīšanas

darbiem. Šajā romānā tiek atspoguļots vēsturisks laikmets, valoda, sabiedriskie sakari, parašas,

apģērbi un rotas. Kā tu to visu spēji izpētīt un cik ilgi pavadīji pētniecības

darbos pirms sāki romānu rakstīt? Vai atradi kaut ko pārsteidzošu? Vai bija arī jāizmanto

māksliniecisku licenci, pašai savu iztēli?

Laimdota: Runājot par romānu

„Cērt zibens marmalē”, jāsaka, ka vēl nekad savā literārajā darbībā

nebiju ieskatījusies tik tālā pagātnē – 14. gs. otrajā pusē. Tas ir laiks, kad Ziemeļeiropā

un Viduseiropā strauji dibinājās un auga jaunas pilsētas, kad milzu ātrumā attīstījās

tirdznieciskie sakari starp Rietumiem un Ziemeļu, Austrumu zemēm. Tagadējās Latvijas teritorija tolaik

bija Livonijas garīgā ordeņa valsts sastāvdaļa; vietējā vidē ienāca kristīgā

ticība, Rietumeiropas modeļa pilsētnieku dzīvesveids un Rietumu preces. Ventspils pilsēta ar ostu,

dibināta 14. gs. 60 gados, bija Hanzas tirdzniecības savienības locekle; svarīgu tirdzniecības ceļu

krustpunkts. Es pūlējos iztēloties, kā nelielā teritorijā saskaras un sadzīvo trīs

tik atšķirīgas grupas kā Livonijas ordeņa bruņinieki (dižcilši un karavīri),

pilsētnieki (tirgotāji, amatnieki, kuģinieki) un vietējie

pirmiedzīvotāji – Kursas turīgie un lepnie ļaudis. Par viņu materiālo pasauli var spriest

pēc arheoloģijas atradumiem – tur ir gan apģērbu fragmenti un rotas, gan ieroči un darbarīki,

protams, ir arī apraksti senos rakstītos avotos – no turienes zinu par Kurzemes izcilajiem zirgiem, par medību

piekūniem utt. Ordeņa pils, kā zini, joprojām stāv; tā ir ļoti daudz pētīta līdz

pat būves pirmsākumiem 13. gs.. Visgrūtāk bija ar valodu, jo neuzskatīju par iespējamu likt

bruņiniekiem vai senajiem kuršiem runāt tipiskā „mūsdienu valodā”; seno vārdu

meklējumi paņēma vairākus gadus. Izklāsts par to būtu pārāk garš, tomēr

varu droši teikt – šie vārdi ir autentiski! To atzīst pat akadēmiski baltu filologi. Diemžēl

šī iemesla dēļ šaubos, vai manu romānu iespējams pārtulkot jebkurā citā

valodā – tulkotājam būtu jāmeklē ļoti sena slāņa vārdi savā valodā...

ja tas vispār iespējams.

Speaking of my novel

Cert Zibens Marmale (Lightning Strikes the Sea), I would have to say, never before in my literary career had I looked

so far back in history—into the second half of the 14th century. That was a time when in northern and mid

Europe many new cities were established and flourishing, when trade routes were being developed at an incredible pace between

west and north and eastern countries. Today’s territory of Latvia was then a part of the Livonian order; in that midsection

entered Christianity, western European style civilization and western goods. Ventspils was a city with a port, established

in the 14th century at around the 60s, and was a member of the Hanseatic merchants league; an important trade center.

I attempted to imagine how three such different groups might relate to one another in such a small territory—the Livonian

knights order (the royals and the military), the city residents (merchants, craftsmen, and sailors) and the original inhabitants,

the proud and well-to-do people of Kursa. One can ascertain something about their material wealth from archeological finds—there

are fragments of wardrobes and jewelry, weapons and tools, and of course some written descriptions—from this I learned

about the great horses of Kurzeme and the hunting exhibitions, and so on. The ancient legion’s castle, as you know,

still stands; it has been greatly studied all the way back to the 13th century. Most challenging was to research

the language, because I didn’t consider it to be accurate to use today’s typical speech for the ancient knights

and Kursa peoples; to research the language of that day took several years. I won’t go into detail on that research,

but can affirm—the language of the novel is authentic! Even the linguistic experts confirm this. Unfortunately, for

this reason alone it is probably impossible to translate this novel—translators would have to research comparable ancient

languages of their own. If such a thing were even possible.

Zinta: What would you like to see Latvians learn from our history? Or, for that matter, anyone of any nationality from history?

Ko vēlies lai latvieši saprot

un mācās paši no savas vēstures? Un vispār, ko cilvēcei vajadzētu saprast no savas vēstures?

Laimdota: Es vēlētos,

lai vairums manu tautiešu vienreiz izmestu no galvas šo „bāreņu sindromu” un beigtu uzskatīt

savus senčus par mūžīgi apspiestajiem, pazemotajiem, nomāktajiem ļautiņiem, kas to vien

darījuši, kā kalpojuši svešiem kungiem paaudžu paaudzēs, un beigtu vaidēt par 700

gadu vergu jūgu. Visi jaunākie pētījumi, īpaši arheoloģiskie, liecina, ka līdz pat

16. gadsimta beigām mūsu senči dzīvojuši visai turīgi, pat bagāti, ja reiz izrakumos atrod

sudraba un pat zelta priekšmetus, bet par verdzībai līdzīgu pakļautību var būt runa, tikai

sākot ar Latvijas teritorijas iekļaušanu Krievijas impērijā politisku intrigu dēļ, un šis

process noslēdzās 1795.g. Taču nepagāja ne simts gadu, kad sākās tautas garīgā atmoda,

strauja kultūras un materiālās dzīves attīstība, nacionālās pašapziņas veidošanās,

kas noveda pie neatkarīgas Latvijas valsts dibināšanas 1918.g. Domāju, ka tikai savai vēstures mācībai

mēs varam pateikties par to, ka izturējām 50 padomju okupācijas gadus, nepazaudējām sevi un

atjaunojām savu valsti. Kāpēc cilvēcei vispār svarīgi zināt savu vēsturi? Lai neatkārtotu

kļūdas, kas kādreiz pieļautas, lai nepadotos grūtos brīžos un nenolaistu rokas briesmu

priekšā, un nezaudētu to, ko izcīnījuši priekšteči.

My wish is that my

people would once and for all abandon this notion of our being some kind of orphans, and to stop looking at our ancestors

as forever oppressed and humiliated and suppressed folk, whose only purpose was to serve their foreign rulers generation after

generation, to stop whining about this 700-year yoke. All the most recent research shows, especially the archaeological digs,

that until the end of the 16th century, our ancestors lived a very wealthy lifestyle, as we find much silver and

gold artifacts, but as for slavery, we find it begins only at the beginning of the Russian Empire, and this ended in 1795.

Not even a century went by that our renaissance began again, a steep curve of cultural expansion and material wellbeing, and

a sense of national identity that led us to declare our Latvian independence in 1918. I think it is only because we learned

from our history that we can be grateful for our ability to endure 50 years of Soviet occupation, that we did not lose ourselves

and were able to renew our nation. Why else is it important for a nation to know its own history? But to not repeat our mistakes,

that once we tolerated, and to not succumb to difficult times and not surrender in the face of threats, and to not lose that

for which our ancestors fought.

Zinta: In large part, your novel is also a very touching story of romance between two people of different backgrounds. Tomass

is a young man who is still untested by life when he meets Ralda, a proud and beautiful young woman who lives in early Ventspils.

Tell us about how you developed these characters, how you chose them to be who they are—and how they may differ from

a young couple today. Ralda, for instance, is something of a feminist …

Tavā romānā parādās

arī aizkustinošs mīlestības stāsts starp diviem jauniešiem no atšķirīgām

pasaulēm. Tomass ir vēl jauns, dzīves nepārbaudīts puisis, kad satiek Raldu, cēlu skaistuli

senlaiku Ventspilī. Pastāsti, kā attīstīji un izveidoji šos divus jauniešus un kā

viņi varbūt atšķiras no šodienas pāriem. Ralda, piemēram, pārstāv sieviešu

tiesības…

Laimdota: Tu saki „something

of a feminist”... hahaha! Nē, tā laikam nebūs vis. Šī meitene par sieviešu tiesībām

neko nezināja un nevarēja zināt. Ir tā, ka 14. gs. Rietumeiropā valdīja kristīgās

baznīcas fanātiķu un sholastu uzskati, ka sieviete ir viltīga, netīra, nelabām kaislībām

pakļauta būtne, kas to tik domā, kā pazudināt labos, tiklos un godīgos vīrusJ, tāpēc tai jāstāv klusu, jāslēpj

miesa, mati, rokas, kājas, mudīgi jāapprecas vai jāiet klosterī. Turpretī Kursā (Kurzemē),

atskaitot kristīšanu un vēl šo to, kūru vidū valdīja agrākās paražas; meitenes

kopš bērnības mācīja jāt, rīkoties ar ieročiem, un, kā rakstīts hronikās,

kaujās viņas cīnījās kopā ar vīriem. Bizes nepina, matus nēsāja vaļējus

„kā raganas”, valkāja pietiekami īsus svārkus, lai varētu jāt zirgā un parādīt

savas smukās sietavas (kājautus)J... Ne velti Tomass, Raldu

ieraudzījis, ir šokā! Taču mīlestība, kā zināms, palīdz saprast pat nesaprotamo

bez noraidījuma vai sašutuma. Tieši šī divu dažādu kultūru un dzīvesveidu sadursme

man likās interesanta, tāpēc arī šie mīlētāji ir tādi. Man liekas, ka viņi

diez vai ļoti atšķiras no mūsdienu pāriem, kur katrs nāk no savas tautas, kultūras un pat

ticības... Varbūt pirms 100 gadiem tā būtu uzskatīta par mezaliansi, bet laikmetos, kad pasaule pārveidojas

(un tāds ir arī tagad), tā ir parasta lieta.

You say, something

of a feminist … ha! No, not really. This young woman knew nothing about women’s rights and couldn’t know.

In the 14th century, the dominant thought in Western Europe among Christian fanatics and scholars was that woman

is evil, unclean, a creature ruled by dark passions, whose only thought is how to seduce the good and honorable men and ensnare

them in her wiles, and so she should be silent, must hide her flesh, her hair, hands, feet, wed quickly or enter the cloister.

On the other hand, in Kurzeme, with the exception of the Christians and a few

others, earlier traditions held among the residents; girls were taught early to ride horses, how to handle weapons, and, as

it was written in chronicles, they fought alongside the men folk in battle. They did not braid their hair, but allowed their

hair to flow freely “like witches,” and wore skirts short enough to allow them to ride horses and show off their

pretty stockings … it’s understandable that Tomass, seeing Ralda, was in shock! But such is love, that it allows

one to understand without judgment or disdain. It was precisely this convergence of cultures and lifestyles that so fascinated

me, so I wrote about these lovers. They no doubt are not so very different from contemporary couples, where each may come

from a different ethnic background or culture or religion … Perhaps before 100 years this was considered scandalous,

but in transitional times, as the world changes, as now, this is quite common.

Zinta: A wonderful addition to this novel are the beautiful illustrations. The illustrator, Ansis Sēlis-Sviriŋš,

is your son. What was it like to work with your son on illustrating the book? Did you tell him what you envisioned? Or did

you simply give him the manuscript and let him loose? Have the two of you collaborated in this way before or is Cērt Zibens Marmalē a first mother-son collaboration?

Romānu skaisti ilustrējis Ansis

Sēlis-Sviriņš, tavs dēls. Pastāsti par šo sadarbību ar savu dēlu. Vai tev bija viņam

jāizstāsta, kā biji iztēlojusies gatavo grāmatu? Vai varēji tāpat iedot viņam manuskriptu

un ļaut viņam pašam to iztēloties? Vai šī jums ir pirmā tāda sadarbošanās?

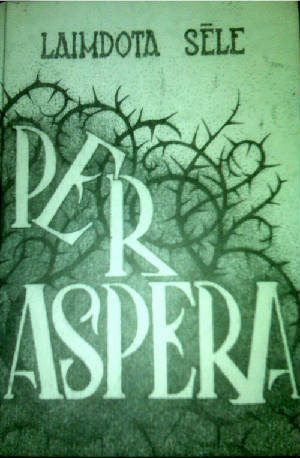

Laimdota: Nē, šī nav pirmā. Mūsu pirmā

tāda veida radošā sadarbība izpaudās manā dzeju grāmatā „Per aspera”,

kas iznāca pirms diviem gadiem. Runājot par šo romānu, liela nozīme ir tam, ka arī Ansis ļoti

aizraujas ar vēsturi un ir piedalījies vairākos ar eksperimentālo arheoloģiju saistītos projektos,

it īpaši kas attiecas uz bruņniecību un seno cīņu

mākslu. Tāpēc viņš ir ne vien grāmatas mākslinieks, bet arī mans konsultants specifiskos

ar 14. gadsimta ieročiem un bruņām saistītos jautājumos. Es nekādā veidā neietekmēju

viņa radošo procesu, un pēc izlasītā manuskripta viņš pats piedāvāja šādu

koncepciju – veidot ilustrācijas kā gotiskus logus, caur kuriem lasītājs it kā var ieskatīties

viduslaiku dzīves ainās.

No, this is not the

first. Our first such collaboration was with my poetry book, Per Aspera, published two years ago. Speaking of this novel,

it is meaningful that Ansis is equally fascinated by history and has taken part in various experimental archaeological projects,

especially those involving knights and medieval jousting. For that reason, he was not only the illustrator for this book,

but also my consultant, specifically on topics of 14th century weaponry and knights. I did not otherwise influence

him in any manner in his creative process, and once he had read the manuscript, he presented this concept—to create

the illustrations to look like Gothic windows, through which the reader could peer onto scenes of medieval life.

Zinta: Are there any plans to translate this novel in other languages? Have any of your other works been translated?

Vai ir kādi tulkojumi padomā?

Vai kādas no tavām grāmatām ir jau tulkotas citās valodās?

Laimdota: Diemžēl nav. Interesei tulkot kādu darbu jānāk no „pretējās puses”;

pagaidām vienīgie manu darbu tulkojumi (daži fragmenti no „Mūsu mīlestības gadsimts”

un kāds desmits dzejoļu) ir krievu valodā; tos tulkoja mana paziņa Ventspils krievu rakstniece Tatjana

Liepiņa.

Unfortunately not. The interest to translate

a work must come from the translator; for now, the only translations of my work (a few fragments of Musu Milestibas Gadsimts

and a few dozen poems) is into the Russian language; those were translated by Ventspils Russian author Tatjana Liepiŋa.

Zinta: The novel ends with something of a cliffhanger, at very least a hint of more story to come … any plans for

writing Part 2?

Romāns nobeidzas ar iespēju

stāstam turpināties. Vai ir kāds nodoms rakstīt turpinājumu?

Laimdota: Nē, tāda nodoma man nav. Lai stāsts turpinās lasītāju iztēlē...

No, I have no such plans. May the story

continue in the imagination of the reader …

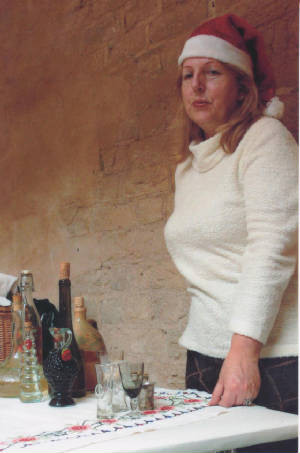

Zinta: The book was unveiled in a historic location in Ventspils, a recently renovated castle. Tell us about that evening

(and oh, I wish I could have been there!)…

Grāmatu atklāja ļoti vēsturiskā

apkārtnē, vecajā Ventspils pilī, nesen atjaunotā. Pastāsti, lūdzu, par šo vakaru (tik

ļoti būtu vēlējusies tur klāt būt!) …

Laimdota: Tiešām, grāmatas atvēršanas svētki notika tai pašā Livonijas ordeņpilī,

kur risinās daļa romāna darbības – savā ziņā unikāls gadījums. To uzsvēra

arī Ventspils muzeja speciālisti (muzejs uz pili pārcēlās pirms gandrīz 10 gadiem, kad pabeidza

lielākās daļas telpu restaurāciju), sakot, ka, atšķirot šo grāmatu, var burtiski izstaigāt

tās pašas gaitas, ko gājuši grāmatas varoņi – komtūrs, bruņinieki, Ralda un

Tomass. Rīkotāji iesaistīja aktierus 14. gs. tērpos, lielajā pavardā dega uguns, smaržoja

zālītes; aktieri lasīja fragmentus... tas bija brīnišķīgi, mani aizkustināja līdz

sirds dziļumiem.

Indeed, the reception for the novel took place

in the Livonian castle, where much of the novel’s story unfolds—a rather unique opportunity. That was brought

up by the Ventspils museum curators (the museum moved to the castle about 10 years ago, when most of the rooms had been restored),

saying that, opening the book, one can literally retrace the steps of the book’s heroes—the commander of the knights,

and the knights, Ralda and Tomass. The organizers of the event had arranged for actors to be dressed in 14th century

apparel, and a fire blazed in the fireplace, the air was scented with ancient grasses, and the actors read fragments from

the novel … it was all so wonderful, I was moved to the depths of my heart.

Zinta: You are not only a novelist, but also a poet, very accomplished in both genres. When and how do you feel yourself

get pulled to write poetry and when prose? Do you sometimes “take a break” from working on a novel to write a

poem, just because that kind of mood strikes you? Or do you work just on a novel at some point, and then, when that is finished,

turn to writing a book of poetry? Do you express yourself differently in poetry than in prose?

Raksti ne tikai romānus, bet arī

dzeju, un esi ieguvusi panākumus abos žanros. Kad un kā juti sevī dzejas balsi un kad prozu? Vai reizēm

rakstot romānu raksti ari dzeju, jeb nododies tikai vienam vai otram pēc kārtas? Vai izsakies citādi dzejā

nekā prozā?

Laimdota: Par tām balsīm grūti izskaidrot. Rakstīt romānu

man nozīmē nepārtrauktu atrašanos tajā pasaulē, kādu nu kuru reizi esmu uzbūrusi.

Pat tad, kad fiziski nesēžu pie datora un neveidoju rindas, tās tikšķ manā galvā... tur

visu laiku kaut kas notiek, veidojas epizodes, risinās dialogi, uzplaiksnī kāds spilgts salīdzinājums

vai metafora... lūk, tagad Tev to saku un nodomāju – ak, vai, tas taču izklausās pēc šizofrēnijasJ... Taču tā ir – romāna rakstīšana

ir nepārtraukts radošs process kādā konkrētā vidē vai laiktelpā. Turpretī dzeja

uzrodas vienā mirklī! Izšaujas no nekurienes un ielec manī, tad nu ātri jāmanās pierakstīt.

Ja tas neizdodas, dažkārt pat labs dzejolis pazūd tajā pašā nekurienē, un nekad nepiedzimst.

Par izteikšanos pašai spriest grūti, var jau būt, ka arī manos romānos dažkārt ir

visai dzejiskas rindas.

It is difficult to explain those voices. To write

a novel means that I must live in that world at all times, that world that I have created. Even when I am not sitting at my

computer putting together sentences, it ticks away in my mind … something is constantly going on there, episodes taking

shape, dialogues developing, a metaphor might suddenly spark … see, even as I describe this, it sounds a bit schizophrenic

… but that’s how it is, writing a novel is a constant and uninterrupted process in space and time. On the other

hand, poetry is born in a moment! It springs from nowhere and jumps into me, so that I have to quick write it down. If that

isn’t possible, a good poem may vanish into nothing and never be born. It is hard for me to determine my own style of

expression; it could well be that poetic lines find their way into my prose, too.

Zinta: Every artist of whatever medium surely feels that our creative works are something like our creative children and

loves them all equally if differently. Are some of your works more special to you than others? Have you written your masterpiece

yet or is that still ahead of you?

Katram māksliniekam nešauboties

savi mākslas darbi kļūst gandrīz kā paša bērni. Vai tev daži tavi “bērni”

sirdij tuvāki par citiem? Vai esi sasniegusi savu kalna galu literatūrā vai tas vēl tevi sagaida?

Laimdota: Jā, tā ir. Es savus darbus tiešām jūtu kā savus bērnus. Un, tāpat kā

nevar pateikt, kurš īstais, dzīvais bērns mātei vismīļākais, to nevar teikt arī

par darbiem. Vai varbūt tā – mīļākais ir tas, kurš pašlaik tiek iznēsāts,

resp., tas, ko patlaban rakstu. Tas vēl ir manī kā nepiedzimis mazulis, tas aug, veidojas, iegūst savu

seju, locekļus, raksturu, kamēr pienāk lielais – prieka un skumju asarām slacītais brīdis,

kad pielieku pēdējo punktu un nospiežu Ctrl+S... Viss! Viņš ir nācis pasaulē... bet man

ir jāpamet pašas radītā, iemīlētā un izsāpētā pasaule... Par kalna galu...

ak, vai! Ceru, ka nē! Mani literārie plāni ir tik lieli... kā Amerika!

That’s true. I really do feel that

my art is like my child. And just as no mother can call any of her children her favorite, neither can I choose a favorite

from among my work. Or maybe I could say—the dearest to me is the one I carry inside me now, in other words, the work

I am creating now. It is still my unborn child, growing, developing, forming a face, limbs, character, until that joyous and

simultaneously tear-washed moment, when I add the final period and … finished! He is born … but I must leave behind

my own creation, a world much loved and birthed with great effort … About a masterpiece… oh dear! I hope not!

My literary plans are still so ambitious … as big as America!

Zinta: You’ve experienced very different times in your life in terms of free speech. How has life changed for a writer

during the Soviet years and today? What are the creative challenges for Latvians today?

Esi piedzīvojusi ļoti atšķirīgus

laikus literatūras brīvā izteiksmē. Kā mainījušies rakstniekam apstākļi salīdzinot

padomju laikus ar šodienu? Kādi radoši izaicinājumi ir latviešiem šodien?

Laimdota: Varu pateikt to, ka padomju laikos man nebūtu nodrukāta ne rindiņa! Dzeju jau iespieda gan,

taču tā bija apolitiska, mīlestība u.t.t. Tajos gados cenzūra strādāja ne pa jokam, pietika

ar mazu nieciņu, lai vai nu darbu noraidītu, vai pašu autoru ieliktu melnajā sarakstā. Varēja

jau prostituēt savu talantu un rakstīt okupācijas varai pa prātam, slavināt komunismu un nozākāt

visus, kas to neslavina... arī tādu autoru pietika, un viņi dzīvoja ļoti labi, saņēma pat

„apbalvojumus”... nezinu, kā viņi šodien, ar kādām jūtām ieskatās savos

agrāk rakstītos darbos. Mūsdienās raksta daudz, autori ir dažādi, tāpat viņu darbi,

ir milzīgas izvēles iespējas lasītājam.

I can say this, that during the Soviet

years not one sentence I’ve written would ever have been published! Poetry, yes, that was published, but it was apolitical,

about love and such. In those years, censure was no small matter, it was enough to include some tiny detail and the entire

work would be dismissed, or the author blacklisted. One could prostitute one’s talent and write to please the occupiers,

praise communism and slander all who do not praise it … there were enough of those authors, too, and they lived very

well, even received “awards… I can’t imagine how they look upon their work today. Today much is written,

authors are diverse, just as their work is, and readers have a wide range of choices.

Zinta: You’ve recently learned to read and speak English, and the story of how that came to be is quite interesting

… and involves a little Muggle magic … please share that story with us.

What other languages do you speak?

Nesen esi iemācījusies angliski

gan lasīt gan runāt, un stāsts, kā to panāci, ļoti saistošs … un tajā ietilpst

mazliet arī Muggle burvība… lūdzu pastāsti mums par to. Kādas valodas vēl runā?

Laimdota: Tas patiešām

ir ērmīgs un jautrs stāsts! Skolā savulaik bez dzimtās mācījos krievu un vācu valodas.

Zināmās politikas dēļ krievu valoda noteikti nebija mans mīļākais priekšmets, tomēr

esmu to apguvusi perfekti un nenožēloju, jo ir ļoti daudz vērtīgu grāmatu, kas nav tulkotas

latviski, bet brīvi pieejamas krievu tulkojumos. Labi zinu arī vācu valodu, tulkoju daiļliteratūru

no vācu valodas latviski. Sarunu līmenī jau pirms daudziem gadiem apguvu franču valodu, taču angļu

valoda joprojām palika „aiz deviņiem zieģeļiem”. Pēc Latvijas neatkarības atgūšanas

angļu valoda sāka aizvien vairāk ienākt manā ikdienā, sākot jau ar visiem computer terminiem,

kam taču vajadzēja izlauzties cauri! Tomēr mans īstais angļu valodas skolotājs ir – ak,

vai kā lasītājs smiesies! – Harry Potter... Notika tā, ka 2001. gadā, kad latviešu valodā

iznāca HP pirmā grāmata, es un mana ģimene, kā arī daudzi mūsu draugi neatkarīgi no

vecuma pēkšņi kļuvām par Roulingas burvju pasaules faniem. Tā nu, nespējot sagaidīt

kārtējās latviski tulkotās grāmatas iznākšanu un zinot, ka dēla draugs pasūtījis

un saņēmis kāroto grāmatu oriģinālā no Londonas, teicu – dod šurp! Viņš

saka: Tev būs par grūtu, zini, cik Roulingai sarežģīta valoda! Es spītīgi: dod šurp,

nav tādas lietas, ar ko es netiktu galā, ja pa īstam gribu! Nopirku pašu lielāko un labāko angļu–latviešu

vārdnīcu un ķēros klāt... Ak, Kungs! Pirmās 100 lpp lasīju veselu nedēļu, galva

un vārdnīca kūpēja, toties pēdējās 100 prasīja tikai pusi dienas. Līdz ar to

kalnam biju pāri, un arī angļu valoda kļuva manējā. Paldies HP un viņa „mammai”

Roulingai!

That really is an odd and funny story! In school,

I once studied, along with my own language, Russian and German. Because of the politics of the day, Russian was certainly

not my favorite, but I learned to speak it fluently and have no regrets, because there are so many valuable books that are

not available in Latvian but have been translated into Russian. I am also fluent in German, and I translate literature from

German into Latvian. I also have a conversation level of French, but English remained unattainable. Once Latvia regained her

independence, English began to enter into my life ever more frequently, beginning with computer terminology, which of course

I had to master! But my true English teacher was—here the reader will laugh!—Harry Potter … It happened

this way. In 2001, when the first Harry Potter book was translated into Latvian, my family and I, as well as many of our friends,

regardless of their age, became great fans of Rowling’s magical world. And so, unable to wait for the translations to

be printed, and knowing that my son’s friends had already received the

newest Potter book from London, I said—give it to me! He said, this will be too hard for you, Rowling uses a complicated

language! I dug in my heels: give it here, there is no such thing that I cannot grasp once I put my mind to it! I bought the

biggest and best English to Latvian dictionary and set to it … My Lord! The first 100 pages took me an entire week,

my head and the dictionary were steaming, but the next 100 required only half a day. With that, I was over the hill, and the

English language now was mine, too. Thanks to HP and his “mother” Rowling!

Zinta: Is it important to you to read other than Latvian literature? I have to say, in the United States, we tend to be

a tad ethnocentric in our literary tastes … we read predominantly American literature, and I think that’s a shame.

Every culture has a unique perspective to offer, a different way of looking at the world that can enrich all of us. I have

found quite the opposite in Europe—a greater interest in reading across international borders. Who are some of your

favorite authors, and what authors have influenced your own work? Of what importance has reading the literature of other cultures

been to you, especially during the Soviet occupation of Latvia?

Vai tev svarīgi lasīt arī

citu valodu literatūru? Jāatzīstas, ASV mēs esam mazliet etnocentriski savās literārās

tieksmēs … mēs lasām pārsvarā tikai amerikāņu literatūru, un man liekas, ka

to var tikai nožēlot. Katrai kultūrai sava perspektīva, atšķirīgs skats uz pasauli, ar

kādu iepazīties var tikai mums visiem nākt par labu. Eiropā liekas pilnīgi otrādi, daudz vairāk

lasa arī citās valodās, citu zemju literatūru. Kādi tavi mīļākie autori un kuri tevi

ietekmējuši? Kāda nozīme tev bijusi lasīt citu valodu literatūru, it sevišķi padomju

laikos?

Laimdota: Esmu izaugusi ar Rietumeiropas klasisko literatūru. Mani vecvecāki un mamma bija kaislīgi lasītāji

un, neraugoties uz padomju režīmu, arī okupācijas gados iznāca ļoti daudz labu grāmatu.

Manus priekšstatus par pasauli ārpus redzamajām robežām veidoja Čārlza Dikensa, Henrija

Fīldinga, Džona Golsvērzija, Herberta Velsa, Viktora Igo, Onorē de Balzaka, Mopasāna, Aleksandra

Dimā, Žila Verna, Tomasa un Heinriha Mannu, Ē.M. Remarka, Ēriha KŁestnera, Selmas Lāgerlēvas u.c. romāni un stāsti. No amerikāņu

autoriem pirmo iepazinu Teodoru Dreizeru, vēlāk nāca lieliskie fantasti – Rejs Bredberijs, Harijs Harisons

un citi. Pateikšu tā: ja nebūtu bijis šo grāmatu, es būtu kā akla un kurla, es, aiz „dzelzs

priekškara” dzīvojot, nezinātu par pasauli nenieka, jo TV līdz pat 90. gadu sākumam bija tikai

3 kanāli (2 Latvijas, 1 Maskavas), bet kinofilmas – lielākoties skaistas (cenzūras izgraizītas)

bildītes. To, kāda pirms padomju okupācijas bijusi Latvija un citas „padomju republikas”, es arī

uzzināju galvenokārt no grāmatām, un pat „padomiski orientētās” varēja lasīt

starp rindām. Lai gan šodien mums pieejama satelīttelevīzija ar neskaitāmiem kanāliem, interneta

bezdibeņi un, protams, iespējas ceļot, es joprojām lasu, cik vien laiks atļauj, lasu visas pasaules

literatūru – latviski, vāciski, krieviski un angliski. Varbūt man ir „lasīšanas atkatība”,

ko?

I’ve grown up on Western European

classical literature. My grandparents and my mother were avid readers, and, despite the Soviet rule, even during the years

of occupation many good books were published. My view on the world outside what I could see was molded by Charles Dickens,

Henry Fielding, John Galsworthy, Herbert Wells, Victor Hugo, Onore de Balzac, Maupassant, Alexander Dumas, Jules Verne, Thomas

and Henry Mann, E.M. Remarque, Erik Koestler, Selma Lagerloff, and other novels and stories. Of

American authors, I was first introduced to Theodor Dreiser, later the major science fiction writers—Ray Bradbury, Harry

Harrison, and others. I’ll say this: if it hadn’t been for these books, I would have been blind and deaf, living

behind the Iron Curtain, and I wouldn’t have known anything of the world, because TV until the beginning of the 90s

had only three channels (two Latvian and one from Moscow), but movies—for the most part, badly censured and choppy.

What Latvia had been like prior to the occupation, as well as other Soviet republics, I learned mostly from books, too, and

even in those censured by Soviets, one could learn to read between the lines. Even while today we can access satellite television

with unlimited channels, the bottomless Internet, and, of course, travel freely, I still read as much as time allows, and

I read world literature—in Latvian, German, Russian and English. Maybe I have declared reading independence, hm?

Zinta: At this point in your career, you work entirely as a freelance author. Something which I quite envy! One of your

ongoing projects has been another novel, serialized for a newspaper. Tell us about that work. How the offer came to you, how

you decided to accept it, and what connection it has brought to you with your readers.

Pašlaik strādā pilnīgi

neatkarīgi kā rakstniece. Jāatzīstas, ka esmu tīri greizsirdīga par to! Viens no taviem projektiem

bijis romāns turpinājumos kādai avīzei. Pastāsti par to. Kā saņēmi uzaicinājumu,

kā izvēlējies šo darbu un kā tas tapa, tāpat arī, kā tas tevi saistīja pie taviem

lasītājiem.

Laimdota: Būt neatkarīgai

rakstniecei ir gan skaisti, gan sūri, vēl jo vairāk globālās krīzes laikā, kas savus nagus

iecirtusi arī grāmatizdevniecībā. Skaisti – jo varu būt neatkarīga savos darbos un to

izvēlē. Sūri – jo jāmeklē tie, kam šos darbus vajag un kas par to maksā naudu. Taču

laikam esmu atradusi vidusceļu, par ko paldies Dievam. Patiešām, esmu sadarbojusies ar savas pilsētas

lielāko laikrakstu tādā veidā, ka viņi publicē manu romānu turpinājumos. Laikam jau

lasītājs, it īpaši, ja līdzekļu pietiek tikai viena laikraksta pasūtīšanai, vēlas

lasīt ko vairāk par dienas ziņām, kriminālo sleju un sludinājumiem. Ja romāns patīk,

tas motivē lasītāju vai nu pasūtīt laikrakstu, vai arī katru dienu to pirkt, kas savukārt

izdevīgi izdevējam. Atzīšos, ka pirmā piekrišana šādam projektam no manas puses bija

pamatīga avantūra... jo nekāda romāna vispār nebija! Es to rakstīju diendienā un, kad man

jautāja, kad tad beigās notiks, godīgi atbildēju, ka nezinu, ko tie mani varoņi galu galā sastrādās.

Tādā veidā varēju epizodēs iepīt pašus aktuālākos notikumus mūsu valstī

un pasaulē, vienu otru „skandāliņu”, piemēram, kā amorāli „onkuļi”

internetā uzmācas bērniem... Manuprāt šī aktuālā „šodienas piegarša”

lasītājiem patika, bet tie, kuri kādu laiku bija spiesti darīšanās izbraukt no pilsētas

vai valsts, bombardēja ar telefonzvaniem, lai uzzinātu, kas notiks romānā, kamēr viņu nebūs

mājāsJ

To be a freelance writer is both

beautiful and difficult, especially in such a time of world economic crisis, which has its talons in the publishing industry,

too. Beautiful—when one can choose work freely. Difficult—because one must find those who need one’s work

and who are willing to pay for it. But I seem to have found some middle ground, thank God. I

have been working with our city newspaper and they have been publishing my novel in chapters. It seems our readers want to

read something more than just the daily news, crime beat and classifieds, especially if a newspaper is all the reading material

they can afford. If they like the novel, they are motivated to subscribe to the paper, or buy a copy each day, which benefits

the publisher. I’ll admit, it was quite an adventure for me to accept the paper’s offer to write a novel in this

manner, because no such novel existed! I wrote it day by day, and when someone asked me what was going to happen next, I had

to answer honestly that I had no idea, whatever my heroes would decide. In this manner, I could weave in current events in

our country and worldwide, the occasional scandal, for instance, how pedophiles are using the Internet to lure children …

It seemed to me that readers liked this relevance to current events, but those who for some reason had to leave town on business,

bombarded us with telephone calls to find out what was happening in the novel, up until they returned home.

Zinta: What are you working on today? What novels

and poetry books are in your future plans?

Ko raksti šodien? Kādi nākotnes

plāni?

Laimdota: Pašlaik strādāju pie jauna romāna, kas būs mana paša pirmā prozas „bērna”

„Spoguļa pārbaude” turpinājums – pēc 20 gadiem. Nesen pabeidzu nelielu populārzinātnisku

darbu – lekciju kursu par dažādiem interesantiem aspektiem Eiropas un citu zemju tautu pasakās. Katru

mēnesi uzrakstu vairākas esejas žurnāliem par ezoteriskām tēmām, dažādiem atklājumiem

un pētījumiem.

Right now I am working on a new novel

that is going to be part two of my first novel, Spogula Parbaude—after 20 years. Recently, I finished a work analyzing

interesting aspects in European and other folk tales. Every month I write essays for magazines on various esoteric themes,

findings and research.

Zinta: Are you considering any trips overseas, perhaps? To America, maybe? We would love to have you visit us here and do

an author’s reading …

Varbūt esi domājusi par ceļošanu

uz Ameriku? Mēs ļoti gaidītu tādu autoru ciemos un lasījumu šeit…

Laimdota: Protams, esmu domājusi un turpinu domāt. Man ļoti patīk ceļot, un es patiešām

gribētu redzēt Ameriku „dzīvām acīm”, nevis tikai TV ekrānā. Man tā šķiet

valdzinoša, apbrīnojama zeme savā dažādībā un... vienotībā. Kā filmā

„Neatkarības diena”...

Of course, I have thought about it and

continue to think about it. I love to travel, and I really would love to see America with my own eyes, not just on a television

screen. It seems a fascinating place to me, awe-inspiring in its diversity and … its union. As in the film Independence

Day …

Zinta: Where, how can readers learn more about you? Have you considered developing a Web site about yourself and your growing

body of literature?

Kur un kā lasītāji varētu

vēl vairāk ar tevi un taviem darbiem iepazīties? Varbūt tiek gatavota kāda mājas lapa par tevi

un taviem darbiem?

Laimdota: Grūti atbildēt. Pagaidām man vēl nav savas mājaslapas, kaut gan draugi jau labu laiku

mudina tādu iekārtot. Jāgaida, kamēr kādam tulkotājam „iekritīs acīs”

kāda no manām grāmatām.

Hard to say. I don’t yet have my

own website, although my friends keep urging me to create one. I will have to wait and see, if my books will catch the eye

of some translator.

Zinta: Thank you so much, Laimdota, for sharing your time and yourself with

our readers. We anxiously await your books, and for those who may not read Latvian, translations!

Sirsnīgi pateicos, Laimdota, par tavu dalīšanos

ar sevi un ar saviem darbiem. Mēs ļoti gaidām turpmākos darbus kā arī tulkojumus tiem, kas latviski

lasīt neprot!

Read a review of Cert Zibens Marmale (Lightning Strikes the Sea).

|