|

|

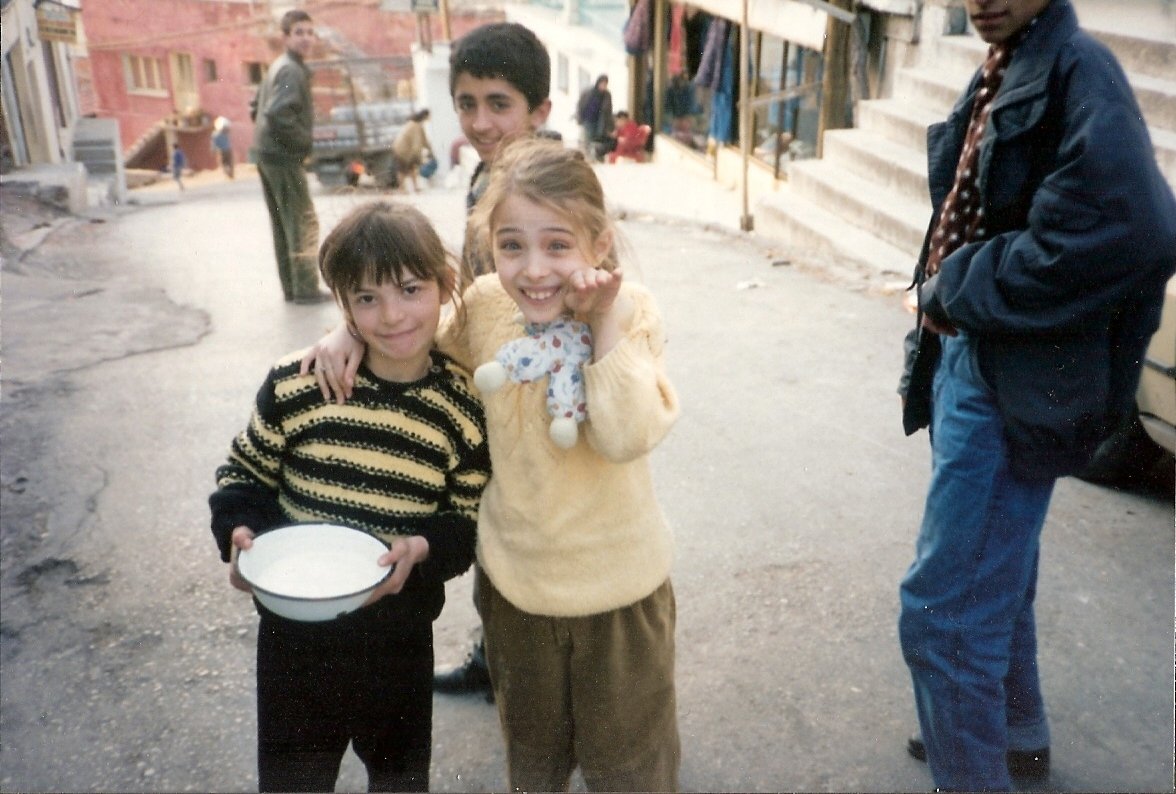

| Photo courtesy of the author |

Children of the Velvet

Fortress

by Rick Steigelman

Our final day in Izmir, and the last

day of our vacation, provides for my mother and me the most pleasant weather of our entire trip. Sunny and 70 degrees. Mom

suggests that we celebrate it with a full day of souvenir shopping. I suggest that she must be crazy. My indelicate choice

of words backs me into the corner of compromise. In an act of near complete selflessness, I agree to join her for just as

long as it takes me to get to the bottom of my own shopping list. She will then be on her own.

When the time finally comes for us

to part, I find myself faced with the dilemma as to whether I truly wish to use up God--only--knows--how--much of such an

ideal afternoon holed up indoors, having the experience that my travel research has implied that I should. And, if not, was

I then prepared to return home burdened by the shame of having failed, while in Turkey, to go in for one their famous baths?

I give in to the silent pressure of

expectation, and am directed to a nearby hotel that I am told will supply me this pleasure. The truth, however, is that my

heart is elsewhere—far from this collection of sweltering rooms that I share with three or four Turkish men in stark

stages of undress. How much different my attitude towards remaining here might be if these baths were made into co-ed affairs,

with my being permitted to pick the participants. But there is no Suggestions box.

Furthermore, with only one masseuse

on duty, it is beginning to look like a bit of a wait for me—and the clock is already reading four-fifteen. Night will

be falling in another couple of hours or so. And, frankly, I have better things to do. To avoid the potential delay that might

be caused by quibbling, I pay both for services rendered and those that I am now choosing to skip. I then head, with haste,

for the door.

On our first night in town, Mom and

I had followed a guidebook recommendation by taking a taxi up to the ruins of the Velvet Fortress, which, from the crest of

Mount Pagos, watches out over both town and sea. We had gone, mainly, for the sunset over the bay.

Built during the reign of Alexander

the Great, the fortress has been reduced to an empty shell of its former imposing self, a thick stone wall encompassing a

plot of open land that, rather than being an integral part of Izmir's defenses, now serves as an area of leisure for the locals.

What had caught my eye that night, as our tired old cab huffed its way up the hill towards our destination, was just how far

removed this neighborhood seemed from the tidy waterfront district in which we were staying. The seaside was modern, cosmopolitan

Turkey. This was the other side.

On that previous trip, Mom had been

a bit of a drag on my exploration of the area; and understandably so, given that she had been one of the few women out on

the streets at the time. And a foreign woman at that. She was not comfortable as a curiosity. This afternoon, I am going alone.

|

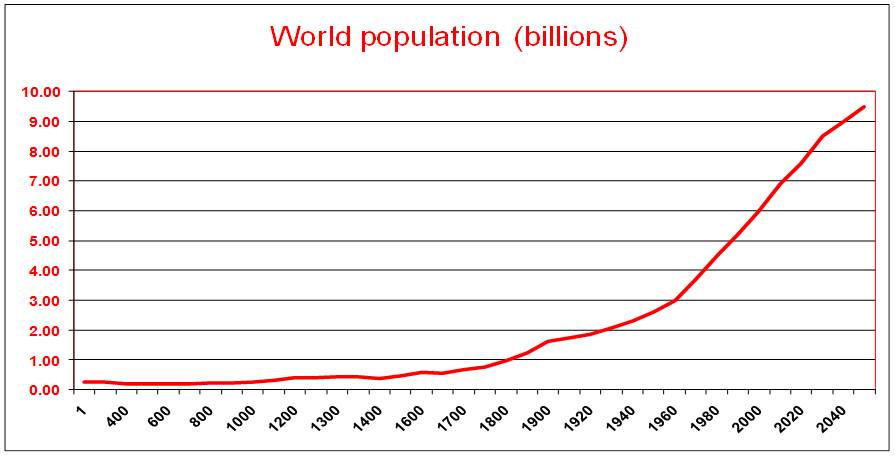

| Photo courtesy of the author |

With the sun simmering towards the

Aegean, I move among the many locals who mingle in front of those shops whose doors are still flung open, or about the kebab

stands and produce carts that occupy the street corners.

It is a poor area. Most tourists, I

suspect, do not visit here. They merely view it through the windows of the cab or bus that is ferrying them to and from the

ancient fortress. Though I am met with a number of smiles, along with nods of greeting, it is, on the whole, a grim-faced

lot.

That is, except for the children. They

are the blessed rays of sunshine piercing the pervading gloom of the surrounding poverty. Too young, I suppose, to have experienced

many of the knocks that life has in store for them, and, perhaps, blissfully unaware that anything much better exists.

Their intrigue with this out-of-place

pedestrian has a much friendlier feel to it than does that of their elders. And whereas I am careful not to train my camera's

lens too conspicuously on any adult, as a precaution against fueling unease, the younger set can't seem to mug it up enough

whenever my camera peeks into view. They smile and wave. They hug and they dance. It is a wonderfully spontaneous audition.

At every turn.

And nowhere is my welcome warmer than

when my wandering takes me up over the hill, past the small lot where the tour buses disgorge their narrowly-focused charges,

and down along the road beyond which clings to the base of the fortress, and which is cast now in the long shadows of the

sun's descent. This stretch looks to be purely residential. I see no shops or food stands. In fact, all I can see confronting

me is a scrum of some two or three dozen children, clogging up the narrow street with their assorted games and shenanigans.

My plan is to pass through and continue on my way.

These kids, however, will have none

of that. I find myself mobbed. But for the difference in religion on their part (along with a few minor moral transgressions

on mine), I very well could have been the Pope. I can't help but feel that, just maybe, I am the first foreigner to whom they've

ever stood close enough to touch. Or at least were comfortable in doing so. As soon as they catch a glimpse of my camera,

the clamoring for a photo session begins. I am happy to oblige.

At one point, I make the mistake of

crouching down to gain a child's-eye angle of those nearest me. I am immediately bowled over, as the back of the pack pushes

forward to get into the picture. Fortunately, my fall is the only thing broken by a brick wall that I do not know is directly

behind me.

My survival at the hands of this adoring

flock is aided by an older gentleman, who gives his name as Selim and who has waded in amid the exuberant youths. He helps

dust me off and recovers for me the box of cough drops that had been knocked from my coat pocket.

This medicine quickly becomes an item

of much interest. Some of the children implore me, with covetous grins, to distribute

the 'seker' (sugar). I pretend not to understand. What teeth they have remaining don't need the 'seker.'

With night now coming on fast, it is

time, I suppose, to find a taxi and retreat to the the civilized world of comfortable Turkey. One young boy suggests to Selim

that he give me his address in the hope, as I interpret it, that I will mail copies of my photographs back to the neighborhood.

I receive his address, fully intending to send him one copy per every recognizable child's face in each of the photographs

that I have taken on all sides of the Velvet Fortress. I can only hope that Mr. Selim will be able to track down every rightful

recipient.

So, it is here, atop Mount Pagos, at

nearly the final hour of the final day of my eight days' journey, that I have recorded my trip's highlight. And, therefore,

to all the guidebook experts, I simply, and respectfully, say: You may have your fat, naked Turkish men in those steamy baths

of legend—as for me, I'll take the children of the Velvet Fortress. Good-bye, my young friends. And look after your

teeth.

Rick Steigelman was born and raised in Muskegon,

Michigan. He moved to Ann Arbor to attend the University of Michigan, after which he descended into a life of bartending.

In addition to publishing one novel, The Hope of Timothy Bean (Briarwood Publications),

he has placed works of creative nonfiction in Superstition Review, Prick of the Spindle,

Hackwriters and Cosmoetica, and had a story earn second place in the Men's

Travel category of the 2010 Traveler’s Tales Solas Awards competition.

|

| By Brent Spink |

Time to Sound the Klaxon?

A personal discussion paper by Alan Stedall

The Challenge!

The human race, as an animal

species, faces a challenge that no other animal has overcome: to survive an uncontrolled explosion of its numbers.

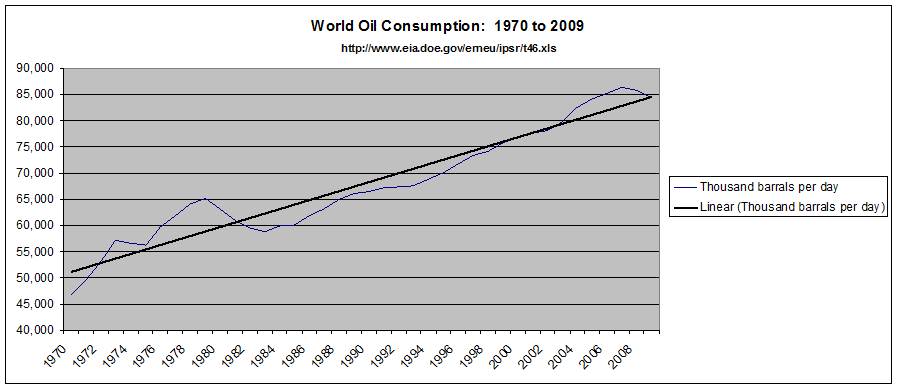

The recent rapid explosion

in our global numbers closely resembles the trajectory of a jet aircraft at take-off.

Hitherto it has been an immutable

law of nature that the numbers of any species, normally kept in check by its predators, availability of food, disease and

other natural constraints will, on removal of this natural balance, explode up to and beyond the boundary limits set by the

species’ environment.

The laws of the jungle and

the Petri dish that then prevail are one and the same: The rapid explosion of

numbers of the species is followed by an equally sudden catastrophic collapse, as the species exhausts its sources of nourishment.

However, we alone, amongst

all other animals, possess the capacity to foresee the dire consequences of a continuing expansion of our numbers.

How Did We Get Here ?

On the birth of Christ our

species numbered c. 250 million. It took 1,500 years for our numbers to double

to 500 million; an average increase of about 167 thousand people per year.

Our global numbers now stand

at c. 7 billion, implying that, since the year 1511, when Henry VIII launched his favourite flag-ship, “The Mary Rose”,

our global numbers have increased by an average of 13 million per year.

That is to say, in the last

500 years our numbers have grown c. 80 times faster per year than in the previous 1,500 years.

In the past century alone,

the human population has almost quadrupled: rising from 1.8 billion in 1910 to

its present 7 billion.

Moreover, our numbers are

projected by the UN to increase by a further 31%, to 9.15 billion[i] in the next forty years, roughly equivalent to the current

populations of China and India added together or the entire human population on Planet Earth as it was in 1930.

Why have our numbers risen

so dramatically, with the real take-off occurring since c. 1750? Conventional

wisdom says that this is largely due to advances in medical science.

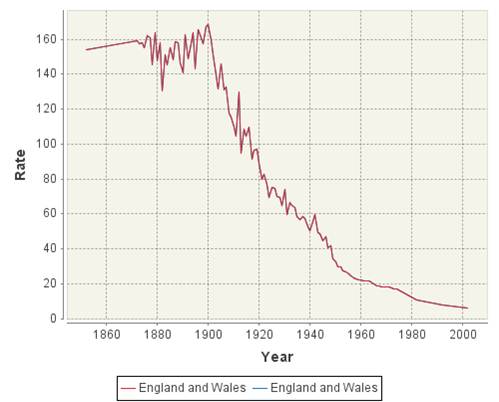

However, if we examine the

historic levels of child mortality within England and Wales [ii]it may be noted that deaths per 1,000 children actually rose

between 1850 and 1900 from 155 to 170, and it was only as from 1900 that the sharp decline in child mortality commenced, before

proceeding to its present level of less than 10 per 1,000 children.

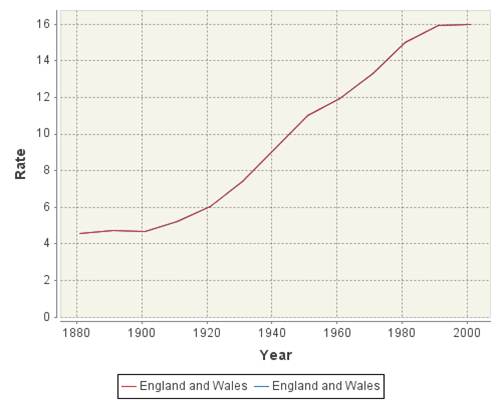

Examination of historic longevity,

percentage of the population aged over 65 within the population of England and Wales tells a similar story. [iii]

From 1880 to 1900 the percentage

of the population in England and Wales aged over 65 remained at less than 5%. It

was only as from 1900 that the percentage of the over 65’s began to rise sharply to its present level of c. 16% [iv].

Yet from 1750 to 1900, the

population in England rose from c. 5.8m to 30.5m[v], a five-fold increase and equivalent to 164,000 per year. This compares

to an increase in population during the previous 150 years (1600 to 1750) from 4.1m to 5.8m; equivalent to just 11,000 per

year.

So we have to look elsewhere

for the massive five-fold acceleration in population growth that occurred over the 150 years from 1750 to 1900.

We find a clue in the historical

cost of transport.

In 1825 an English labourer

would have had to part with a third of his weekly earnings for a ten mile stagecoach trip from Blackburn to Preston. By 1850, however, the cost of this same trip by railway was less ten per cent of his

weekly earnings. In other words, in just two decades, the replacement of animal-drawn

transport by steam-drawn transport had reduced the cost of transport by a factor of 4.

The historic retail price

of goods[vi] tells a similar story.

A craftsman in 1750 would

have had to have worked 4.7 days to earn sufficient money to buy the same basket of foodstuffs that by 1900 he would have

needed to work only 1.7 days.

In other words, versus their

costs in 1750, by 1900, steam-driven improvements in manufacturing industry and transport had reduced the real costs of foodstuff

by a factor of almost 3.

I suggest that the five-fold

increase in the English population that occurred between 1750 and 1900 was permitted only as a result of the dramatic reduction

in the real price of food-stuffs and other goods, resulting from the replacement of primitive animal, water and wind-driven

technology with coal, gas and oil-driven technology.

In effect, our species has

enjoyed a one-time “spending spree”; burning in just a few hundred years a windfall of the energy that was stored

by other pre-historic life-forms over tens of millions of years.

We have used the released

energy as a powerful industrial and economic “lever” to permit an increase in the numbers of our species, far

beyond that which our previous non-fossil fuel existence could ever have permitted.

But fossil fuels, by their

nature, cannot be replenished.

And the most valuable and

versatile of them, oil, is by general consensus already near the “peak” levels of available supply.

The key fossil fuel: Oil!

Nothing, but nothing, is

so versatile and pivotal to the support of our civilisation as oil.

While a city-commuter car

powered by electricity may be within our grasp, an electrically powered aircraft is a long way into the future; coal-fired

ships and coal-fired trucks are a long-way behind us and there are only a handful of nuclear powered commercial ships.

And while our species’

global thirst for oil is increasing; its finite supply is inevitably dwindling.

Since 1970 the price of oil

has risen by 185% in real terms and the per annum increases are gathering pace.

Assuming that the real price

oil continues to rise at an average of just 5% year on year, this would imply that by 2040 the price of oil will be c. 4.5

times what it is today; feeding into the global cost of transport, shipping, air travel and general manufacturing, in particular

in the production of plastics. These cost increases will ramp up the cost

of basic commodities for a world population c. 31% greater than it is today.

The key message from the

above is that the cheap fossil fuel “lever” that has supported the explosion of our species, commencing in 1750,

and more latterly our global economy, is now fast falling away. And the most valuable and versatile of these fossil fuels,

oil, is falling away fastest.

The progressive removal of

the lever of cheap fossil fuel will lead to impoverishment on an unprecedented global scale, as the basics of life become

increasingly unaffordable for much of the world population. This economic decline

will drive social unrest, mass immigration and a polarisation of politics on a world-wide scale: Our present life-style in 2011 will become a nostalgic dream of a past “golden age” (believe

it or not).

What can be done about the

situation?

Nothing can be done to prevent

the progressive depletion and eventual exhaustion of fossil-fuels. We can attempt

to create synthetic oil from plant sources, but this will never be as widely available, or as cheap, as extracting the stuff

out the ground[1].

The price of any commodity

is a function of supply vs. demand. While we cannot increase the volume of the

remaining fossil fuel reserves, we can take action to reduce our demand upon them. And

to avoid human suffering on a massive scale, it is vital that we should do so on an urgent basis.

To reduce our demand for

oil we can:

a) Apply improved and more fuel-efficient technology to eke out our remaining oil

reserves.

b) Increase our use of other forms of energy, including solar, hydro, wave, tidal,

geo-thermal and nuclear [2].

c) Reduce our per capita consumption by electing for less materialistic consumer

life-styles.

However, at their very best,

the above actions will simply defer the exhaustion of fossil fuels, they cannot prevent it.

The stark

fact remains that, on the progressive exhaustion of fossil fuels the world will be revealed to be massively over-populated

as it emerges into a “post fossil fuel age”.

This “reveal”

will take the form of ever-increasing prices for the basic commodities of life; threatening increasing millions of world-wide

poor with malnutrition, exposure and disease.

Hence we can and should strive

to reduce the future “population overshoot” to the greatest extent possible, in stark recognition that nature

will bring about, in an uncontrolled, chaotic and inhumane manner, savage reductions in the size of our population that we

have failed to deliver by considered and humane methods.

Globally:

We must strive to educate

overseas countries as to the need to reduce their populations on an urgent basis if they are to mitigate the effects of mass

starvation due to ever-increasing food prices.

Overseas food aid programmes

need to be accompanied by family planning programmes if we are not to deceive poorly educated peoples in the developing world

into believing that their numbers can increase indefinitely on the back of a never ending supply of overseas food aid from

the developed world.

Within the developed world:

It is clear that we in the

developed world, with our disproportionate consumption of the world’s resources, also urgently need to reduce the numbers

of our population. Else we are “sleep walking to disaster”.

It has been said that, as

the present Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in the UK of 1.9 is below the replenishment rate of 2, then we need not drive for any

further reduction[3]. Given the extent of challenges implied by a post-fossil

fuel world, this is palpably untrue.

Additionally, a significant

percentage of the forecast increase in UK population, from its present level of c. 61m to the forecast 71m by 2031, will be

as a direct or indirect result of immigration.

This implies that we in the

UK need to re-double our efforts to educate, campaign and agitate to bring awareness to the above issues with a view to:

(a) Driving the UK TFR down to one or less within the next twenty years.

(b) Reducing net immigration to zero, i.e. “one in, one out” at the boundaries of the

European Union.

Through our above efforts

we must strive to preserve the hard-won civilised qualities of today’s democratic nations, knowing that these virtues

cannot survive in the increasing barbarism of a world of nine billion souls denied the platform of fossil fuels.

Once the first few of the

passengers on the Titanic knew the ship was sinking they had a choice; they could pass the knowledge on in whispers to their

fellow passengers; they could sound the ship’s klaxon; or they could slope off and make sure that they and their families

were first in the life-boats.

I suggest the time is now

over-due to sound the ship’s klaxon.

[v] Wrigley and Schofield, "The Population History

of England, 1541-1871. A reconstruction.", Harvard University Press, 1981, Table 7.8, pgs. 208-9,

[vi] http://gpih.ucdavis.edu/files/England_1209-1914_(Clark).xls

Alan Stedall was born in London, England, just after the

war. Alan is an IT professional and programme director who has led several major business change projects in a number of “blue

chip” commercial organisations and government agencies. He is a trustee and vice-chair of a UK registered charity, http://populationmatters.org, that campaigns for a sustainable future for humanity

and the environment. He is also author of Marcus Aurelius: The Dialogues; a work

that explores the philosophy and moral beliefs of this pre-Christian, Stoic Roman Emperor. Alan is married to Vivienne and

lives in Birmingham, England.

|